A tasty serving of history

"The Cookbook Library" mines a rich collection of works dating to the 1400s.

It was 20 years ago that I left Chateau du Fey, the 16th-century castle in Burgundy where I'd spent a magical year working for my culinary degree at Anne Willan's École de Cuisine La Varenne.

As a stagiaire translating French cooking classes for the English-speaking students, this was my springboard into the world of food. I had the run of the estate, from the wine cellar to the vast cookbook library to the walled potager garden. I knew where they kept the truffles.

There was one door, however, that was always locked. Behind it, others whispered, was a collection of rare antiquarian culinary books owned by Willan and her husband, Mark Cherniavsky.

With the publishing of The Cookbook Library (University of California Press) in April, that door is at long last open. And what I discovered inside is one of the best lessons Willan ever taught: the priceless value of true culinary history.

"Old cookbooks are captivating, and important too, leading us into the world beyond the hearth," writes Willan in this beautifully illustrated survey of their 200 books, dating from 1474 to 1830.

As she leads readers from the floridly spiced "hochepots" of medieval master chef Taillevent, to the visionary Renaissance kitchen of Bartolomeo Scappi's Opera, to Francois Menon's 1746 La Cuisinière Bourgeoise, it's clear this book is as much about the evolution of European society as it is about what they ate. Whether it was the medieval spice trade (when a pound of nutmeg was worth seven fat oxen) or the 16th-century sugar rush (coinciding with colonial expansion), Western history lies in these ancient recipes.

Who knew that Nostradamus, the French apothecary and future-teller, also penned "a little book on preserving" in 1555, among the first with precise recipe measurements.

"Nostradamus has clearly stood over the stove himself, watching the quince syrup boil," Willan writes.

Willan has done much recipe testing herself over the last 30 years, publishing 35 cookbooks . The Cookbook Library is a more academic project, however. And the timing is intriguing, given the explosive growth of the industry. In 1972, 324 cookbooks were published, according to Bowker's Books in Print. By 2011, new titles had ballooned to 4,634 (including 722 e-books). Add 16,773 food blogs, according to Technorati, plus television food shows, and millions of Twitter feeds and Yelpers, and our modern world is gorging on a historic feast of food info. But, in a Google-first, Wikipedia era, an incalculable amount is recycled.

There may be no better refuge than these ultimate primary sources, where modern turducken lovers will discover they have nothing on Hannah Glasse's Yorkshire "Christmas-Pye," which stuffs five deboned birds one inside the other, sealed in a buttery crust. Willan owns a first edition of Glasse's The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy, a 1747 British classic, a staple in American Colonial kitchens.

"It is indeed an extraordinary experience to be able just to walk over . . . and consult books dating back to 1491," Willan writes. "The feel in the hand, the density of type, the condition . . . pristine or battered, allow us to know each book as we would know a friend."

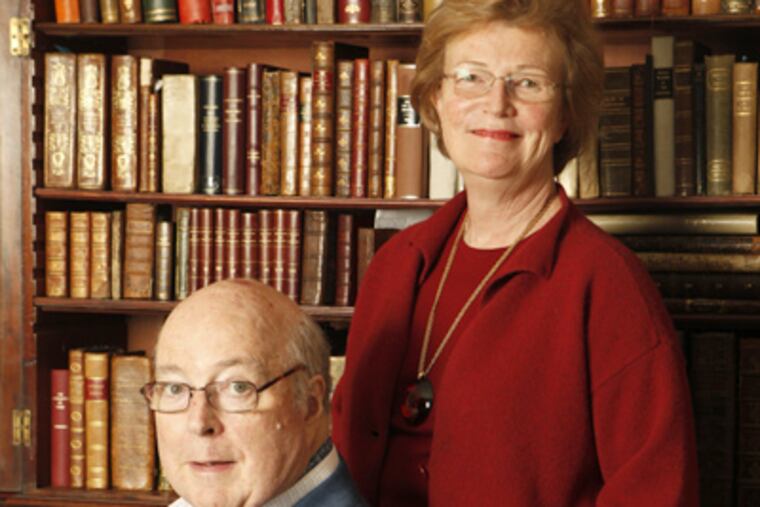

That personal connection infuses this entire book because it began as a collaboration with her husband, a devoted collector who gifted her with many volumes since they were married in 1966.

" 'If you're going to write about cooking you've got to have a library!' " Willan recalls him saying before their first splurge on "a couple hundred" used books. Among their earliest acquisitions: The Joy of Cooking, The Gourmet Cookbook (she then worked there answering readers' letters), Larousse Gastronomique, and, of course, books by "Jim" Beard.

"Anne and I do not collect cookbooks as trophies - we use them!" writes Cherniavsky in his afterword.

As I thumbed through a 17th-century chapter on the feats of one chef who innovated the use of stock, ragouts, roux, seasonal cooking, and beurre blanc, I realized Cherniavsky wasn't kidding. The chef? François Pierre de la Varenne, namesake on that culinary degree Willan handed me 20 years ago.