How to know when it’s time for hospice

Hospice is meant for people who are likely to die within six months. What are the signs that your loved one might qualify?

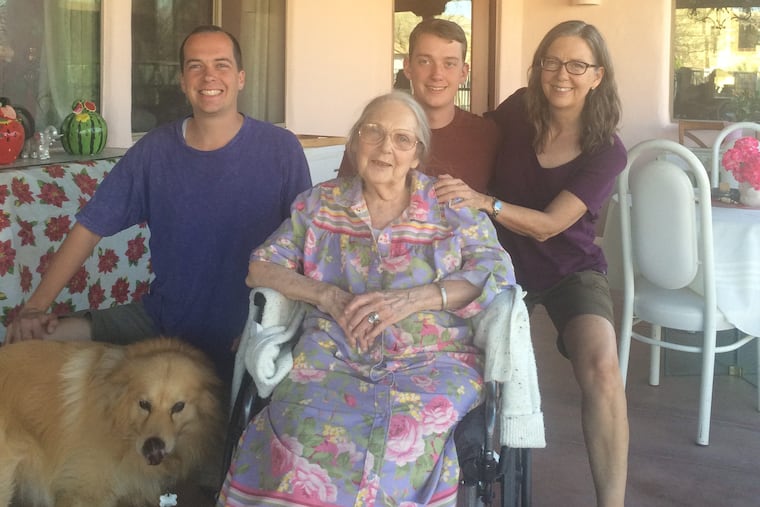

The owner of the assisted-living facility where my mother lives recently suggested to my brother and me that we enroll Mom in hospice.

We were surprised. Our mother is old — 88 — and frail. She has moderate dementia, but no other major diseases. She is declining, physically and mentally, very slowly, as she has been for years. Faced with a version of the classic question experts recommend for doctors who are considering a patient for hospice — Would you be surprised if your mother died in six months? — I would say no. (Hospice programs are meant for people who are expected to die within six months.)

Mom is fragile, and a routine virus or fall could kill her quickly. We know that every day is a gift. But this has been true for years.

I could also answer no to this question: Would you be surprised if your mother was alive in six months?

My brother is a retired professor who studied psychological aspects of death. I am a medical reporter who has written frequently about hospice and had to enroll my husband in it. But neither of us knew what to do about Mom.

The episode made me think about how hard it must be for people who know even less about hospice than we do to guess when someone is within six months of death. Maybe this is one of the reasons that people tend to join hospice within days of death, too late to experience all of its benefits.

Hospice provides services aimed at caring for people at the end of life, not curing their ailments. Care is usually provided in people's homes. Hospice provides some hands-on care, management of pain and symptoms, and drugs and supplies.

I set out to write a practical guide that would help family caregivers know when a loved one is in the last months of life. What are the signs and symptoms that death is approaching?

To find out, I asked Lori Bishop, vice president of palliative and advanced care at the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization; registered nurse Susan Foster and physician Nina O'Connor, both leaders at Penn Wissahickon Hospice; Scott Halpern, director of the University of Pennsylvania's Palliative and Advanced Illness Research Center; Salimah Meghani, who teaches in the palliative care program at Penn's School of Nursing; and Diane Meier, a geriatrician who directs the Center to Advance Palliative Care at Mount Sinai School of Medicine.

My hopes of a simple list were quickly dashed. These experts told me that even doctors and nurses have trouble predicting death.

"We don't know when people are going to die," Meier said. "It's just not given to us." Doctors are much better, she said, at knowing when patients need extra help.

Halpern agreed that doctors are "terrible" at predicting death, but said they typically do know when their treatments are likely to improve length and quality of life and when they won't. They're not always good at conveying that information to patients.

>> READ MORE: He was 93 and dying. He wrote a comedy about it

The predictions get better the nearer someone is to death. They are also easier to make in patients who have cancer — the disease for which hospice programs were created — than in those who have other common causes of death such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, Alzheimer's disease, and heart failure. My mother's primary problems, old age and frailty, are particularly tough. People in her condition can do well for a long time, but may decline rapidly if they get pneumonia or break a hip.

Keep in mind that palliative care may also be an option. It is designed to relieve distressing symptoms such as pain, but is not based on prognosis and does not require a patient to forgo curative treatment. It also does not provide as many services as hospice. Hospice benefits can be extended if patients do not die within the initial six months, but programs may be penalized if they enroll too many long-lived patients. People may also be discharged from hospice — many people actually do better on hospice than when they were getting more medical treatment — but can reenter later.

Although cancer prognosis is the easiest to predict, cancer patients often spend only a few days in hospice. In part, this may be because they tend to do fairly well until they figuratively "fall off a cliff," Meier said. These are people who are well enough to go on a vacation, then are suddenly too weak to stand. Sudden decline is often a sign that death is approaching, she said.

Multiple rounds of treatment are also a red flag. "When you've failed a third round of chemotherapy and they're talking about a fourth round, you need to question where you're at in this battle and how you want to spend your time," Bishop said.

If a cancer patient is spending more than half the day in bed or a chair, that is a sign, Meier said, that they could die in two to three months. That is not the case with dementia patients, who can spend years mostly in bed or in a wheelchair.

In general, experts such as Meier look at a "gestalt" that includes functional decline, worsening quality of life, and an increasing number of medical crises. "You look at their day-to-day life compared to six months or a year ago," she said.

Here are some changes that are warning signs:

Needing help with an increasing number of key daily activities, such as dressing, bathing, walking, eating, or using the toilet.

Eating and drinking less.

Talking more about people who have died than people who are living. Social withdrawal, especially in formerly outgoing people.

It's harder to get the patient to the doctor or hospital.

Current treatments aren't working, and doctors say there's nothing new to offer.

In people with dementia, trouble with swallowing is an important harbinger.

There have been multiple trips to the hospital or emergency department in the last few months, and the patient hasn't bounced back after returning home.

Pain is getting worse.

The patient is experiencing infections or pressure ulcers.

Halpern thought I was asking the wrong questions. Though he is working on tools that will help doctors and nurses better align care with what patients with serious illness want, he thinks it's a "useless activity" for doctors to try to figure out who is going to die within six months. Much more important is knowing how to help patients live how and where they want with a good quality of life as long as possible.

The current hospice rules, he said, are "highly outdated." He said Medicare is "coming around to that view" and testing different models.

My mother's case still isn't clear. The experts weren't sure whether she would qualify for hospice, either. But they did make me think it's a good time to have another talk with her about her treatment goals. And, it may be time to start evaluating hospice programs so we'll be ready when things change.