WiFi can detect bombs and chemicals, Rutgers engineers say

The key is that wireless signals pass through the materials used to make bags and suitcases, but not so much through metals and liquids.

Airport-style metal detectors are an effective tool for flagging weapons and other potential threats, but the large, walk-through scanners are beyond the budget of many institutions that need to handle big crowds in short order.

In a new study, Rutgers University engineers reported they could make a low-cost alternative using technology already present in your living room or neighborhood coffee shop: WiFi.

The key is that these ubiquitous wireless signals pass through plastics and fibers used to make suitcases and bags, but they tend to get scattered or reflected by metals and liquids.

By analyzing how the signals pass through different materials, the researchers were able to write a detection algorithm that picked out "suspicious objects" inside bags with greater than 95 percent accuracy, they said.

The accuracy rate dropped to 90 percent when the objects were wrapped in an extra layer of material, but the researchers are confident they can boost that number by tweaking their system, said Yingying Chen, a professor of electrical and computer engineering at the Rutgers New Brunswick campus.

Chen and her Rutgers colleagues collaborated with researchers at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis and Binghamton University, winning a best paper award at a June conference in Beijing.

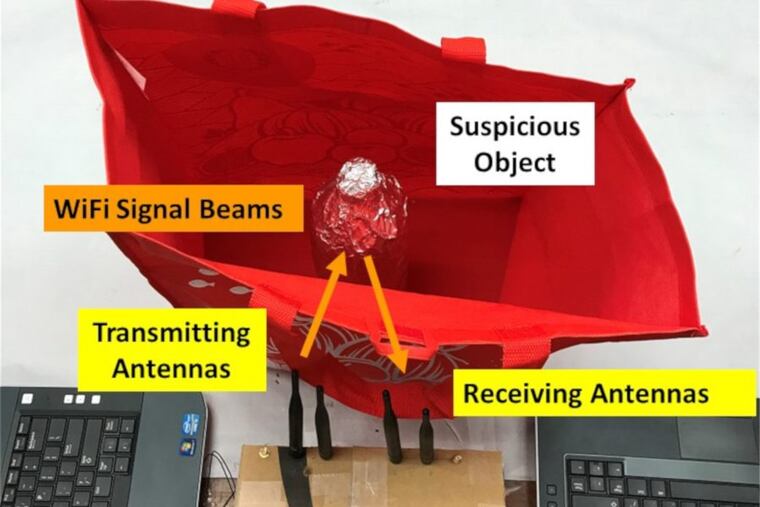

The authors tested their method on 15 metal and liquid objects inside six types of bags, using a simple setup with antennas, a laptop, and the basic WiFi signal on the Rutgers campus. They tested metal objects that stood in for weapons and harmless liquids that took the place of explosives ingredients.

The initial system was meant only to demonstrate that the WiFi concept was feasible. Before it could be deployed in a real security setting, the researchers say, they want to improve the system's ability to distinguish different kinds of metals, among other refinements.

In many crowd situations, current screening procedures involve lots of personnel.

"What they do is hire a lot of people to open backpacks," Chen said.

A better option would be to use the WiFi technology as an initial screening tool, she said. If the algorithm detected anything amiss in a particular bag, security personnel could then search it the old-fashioned way.