Even as Americans kick the habit, Zippo's eternal flame burns bright in rural Pa.

As more Americans kick the habit, executives at Zippo are accustomed to gloomy speculation about the future of the iconic lighter. But the company has seen $200-million-plus in annual sales in recent years, thanks to increasing demand in Asia and Europe, where Zippo has opened both offices and storefronts.

BRADFORD, Pa. — The typical Monday blues were below zero here because of a fresh half-foot of snow that covered this Northwestern Pennsylvania city and a heartbreaking Steelers loss that buried it.

Yet no matter how far temperatures fall or how games end, an eternal flame burns in the Allegheny Mountain community of 8,369. Zippo, maker of an American icon, is the largest employer in rural McKean County, and since 1932, it has produced more than 569 million lighters, every single one stamped on the bottom with "Bradford, Pa."

"Cold hands, warm hearts. That's what they say about Bradford," said longtime employee Barb Reid, 73.

In most rural Pennsylvania counties, top employers are school districts, medical groups and hospitals, state government, and WalMart. While all of those industries do employ residents of McKean County, which sits on the New York border 316 miles northwest of Philadelphia, they all fall behind Zippo.

Bradford emerged as one of the state's oil boomtowns in the late 19th century, thanks to a high-grade crude still extracted here today. Zippo inventor and founder George G. Blaisdell worked in the oil industry, and one windy summer night in 1932, he watched a friend struggle with a clunky, Austrian-made lighter and drew up plans for Zippo's "windproof" lighter.

Today, Zippo has 610 employees, is still private and owned by Blaisdell's grandson, George Duke. It remains the county's top employer despite increasing automation and layoffs, and a successful effort by government health agencies to reduce the rate of smoking in the United States.

"Without Zippo, we wouldn't be here I don't think," Terri Perkins, 63, a former employee, said of Bradford from behind the counter at a downtown vape shop.

Residents have speculated about what would happen if Zippo ever closed or moved. All across rural Pennsylvania, small towns and cities tied to industries like coal and steel have suffered greatly when the market left those industries behind. The closest city is Buffalo, 80 miles north, so losing Zippo would make McKean County feel more out-of-the-way than it already is.

"This is the most rural and most isolated area of Pennsylvania," said Mayor Tom Riel, a Republican in his 11th year in office.

Executives are accustomed to speculation about the company's doom, but Zippo has seen $200-million-plus in annual sales in recent years, thanks to increasing demand in Asian and European markets, where Zippo has opened both offices and storefronts.

"We're exporting into 180 countries," said Richard Finlow, Zippo's vice president of sales and marketing. "Sixty percent of our business is exports."

China, according to the Washington Post, is the world's largest consumer of cigarettes, and that's why the backs of some executives' business cards are written in Chinese, and why Zippo's Chinese zodiac lighters are top sellers. Zippo has also expanded its line of hand warmers and is venturing into the world of outdoor gear and clothing and glasses

"Our company is very healthy," said president and CEO Mark Paup. "We're in acquisition mode. We're in innovation mode. We're in diversification mode."

While Bic has sold 30 billion of its affordable, plastic lighters worldwide, Zippo doesn't view the French company as its chief rival. Competitors in Asia making fake Zippos cause the company its biggest headache, and it guards its factory, asking the Inquirer and Daily News to not take photographs of specific machines.

Zippo might be changing, Paup said, but little Bradford is key to the company's global brand.

"In my 24 years with the company, there has never been a discussion, ever, about moving the company," Paup said. "That lighter is going to say Bradford, USA, or we won't exist. That's ingrained in the minds of our customers and distributors. It wouldn't be Zippo if it wasn't Bradford."

The Zippo plant floor is broken down by a series of processes that begins much the way it did in the early days, with 1,500-pound coils of brass that are pressed into each lighter's boxy form. The squat factory is capable of making 40,000 lighters a day, but like many industries, an increasing number of computer-run machines help make that possible. The company is nonunion.

"It really hasn't been a big source of tension because our workforce is older," said Tim Van Horn, Zippo's vice president of operations. "Every year we have 10 to 15 people who retire."

Still, Zippo laid off 53 employees last year, citing slowdowns in the North American market. That move alone may have made McKean County's unemployment rate tick up to 5.7 percent as of November — higher than the state average of 4.6 at the time, but lower than the rate in Philadelphia, 6.2 percent.

McKean County voted overwhelmingly for Donald Trump in 2016, as well as every other Republican presidential candidate since 2000, the last year available on a state database.

Almost everyone in the nation knows the look and sound of a Zippo. The lighters were handed out to soldiers during World War II, burned into the American consciousness. Frank Sinatra was buried with his Zippo. Grooms often buy them for their whole wedding party. The brand is in approximately 30 to 40 movies and television shows per year.

"It's not just a functional way to light a cigarette," Van Horn said. "It's a symbol. It's a part of you. People who might not even smoke buy them."

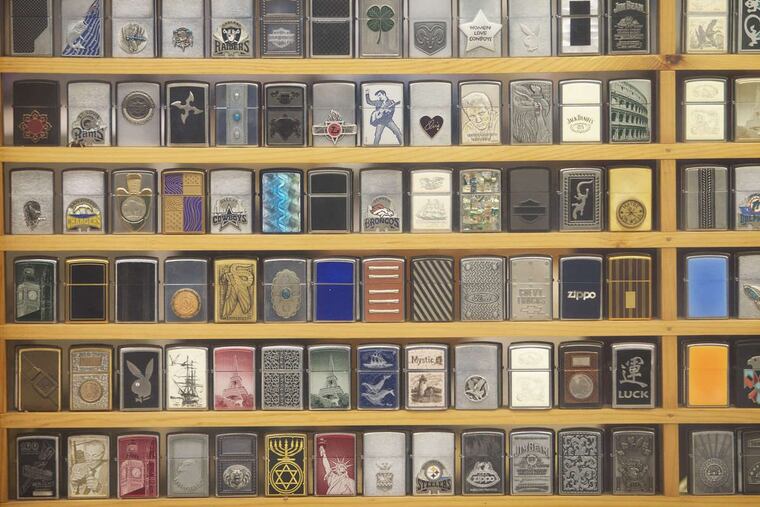

In America, big sellers include Harley Davidson-themed lighters and anything whiskey or sex-related.

"Playboy, Jim, and Jack, we like to say," Van Horn said.

Almost everyone in Bradford knows someone who was or still is employed by Zippo. At the VFW on recent day, where Zippo lighters sat on the bar atop packs of Seneca cigarettes, the bartender and five customers all worked for Zippo or Case, the knife company it purchased in 1993. Neon Zippo signs light up the night sky. There's a bar across the street from the corporate offices on Barbour Street called the Lighter Side. A museum near the factory claims to be the most visited in Northwestern Pennsylvania.

"My mom works for Zippo. She loves her job," said Mike Fay, 39, a Bradford resident who used to be a Zippo employee. "My dad is retired from Case."

Barb Reid, a maintenance clerk, occupies a wood-paneled office filled with dozens of pictures of fellow employees' prize fish, their trophy deer, and at least a dozen Little League players who, by now, could have budding baseball players of their own. At 73, she's the unofficial mom to dozens of workers there, the biological mom of two.

Reid's son has worked there for 30 years. Her daughter works three feet away from her.

"She likes it like this, so she can boss me around," said Donna Miller, 53.

Reid has worked at Zippo through all six Steelers Super Bowls. At the luncheon to celebrate her 50th anniversary with the company, Zippo gave her a custom Steelers lighter.

"What an ugly game," she said of the team's recent loss to Jacksonville.

Van Horn said Zippo still hands out turkeys for Thanksgiving and hams for Christmas. When an employee with perfect attendance for two decades came to work after his home burned down, he said Zippo replaced each of the lighters in his beloved collection.

Zippo and the Blaisdell family are arguably Bradford's biggest philanthropists, donating money to the local hospital, YMCA, SPCA, and the University of Pittsburgh's Bradford campus.

"They've been very good to us and very good to this area," said Dennis J. McCarthy, of the Bradford Regional Medical Center, the county's second largest employer.

Mayor Riel, whose mother retired from Zippo, said the company helped refurbish city council chambers and his own office and helped fund a camera system in a downtown business district.

"There's just too many things to name." he said of Zippo's community involvement.

Outside the Zippo warehouse, employee Casey Schweikart, 51, was brushing snow from a delivery truck. He said he has worked almost every job at Zippo over the last 30 years.

"I've pretty much enjoyed them all," he said. "There's not many companies left like this one."

An image of a mother and son, gazing into a campfire lit presumably with a Zippo product, covered the truck. Neither one was smoking.