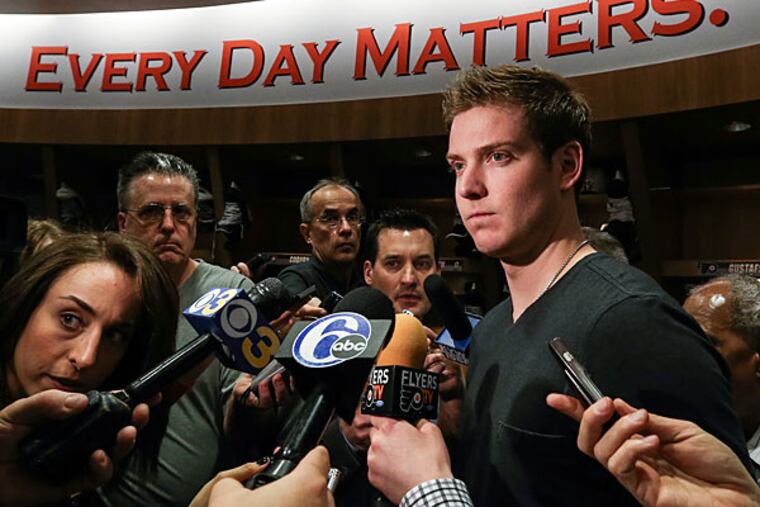

Mason's path back to ice after concussion

On the morning of what, to that point, would be the most important hockey game of his life, Steve Mason wasn't certain he would play until after they had removed the needles from his head.

On the morning of what, to that point, would be the most important hockey game of his life, Steve Mason wasn't certain he would play until after they had removed the needles from his head.

The headaches had returned the day before, that same dull throbbing that he'd lived with for a week after suffering a concussion against the Pittsburgh Penguins on April 12. Only now Game 4 of the Flyers' first-round series against the Rangers was less than 12 hours away, and Mason had expected to start in goal. No, that wasn't quite right. In his mind, he was obligated to start Game 4.

His symptoms had subsided long enough for Flyers coach Craig Berube to dress him as the team's backup goaltender for Game 3, for Berube to tell reporters just two hours before that game's beginning that yes, Mason was completely healthy again. But now the headaches had come back, and his team was losing the series, two games to one, and here he was lying on a table, allowing an associate of Flyers trainer Jim McCrossin to perform acupuncture on his, Mason's, scalp and neck to try to relieve the pressure and the pain.

It worked.

Was it worth it?

Steve Mason was the most compelling story of that Flyers-Rangers series. There wasn't a close second. It wasn't just that he was the series' best player, carrying the Flyers to wins in Games 4 and 6, saving his finest performance for their 2-1 loss in Game 7. It was the accompanying drama: the question of whether he would play at all, the influence he might exert on his team's success or failure, the timeless allure of an athlete willing to endure supreme tests of his body and spirit for the sake of competition and victory.

But there was another factor at play: the nature of Mason's injury. Concussions have become a flash point throughout sports. They're introducing new terms and discussions and dangers into our games' traditions and intrinsic qualities, into all kinds of things we used to take for granted. What do you mean baseball should do away with collisions at home plate? . . . Can't anybody put a hand on a quarterback anymore without a ref throwing a flag? . . . What is this disease "chronic traumatic encephalopathy," and do you really think that it's causing people who played football and hockey to kill themselves?

The confusion over Mason's status during the Rangers series struck at the core of these questions - questions that the Flyers have reason to consider carefully, maybe more than most franchises. Remember: This is an organization that, over the last decade and a half, has seen the careers of three of its most consequential players cut short by concussions: Eric Lindros, Keith Primeau, and Chris Pronger. Yet it wasn't until Friday, the Flyers' getaway day, that Mason and Berube traced the arc of Mason's return to the lineup and, in doing so, illuminated why these questions are so challenging.

Not long after the Penguins' Jayson Megna charged into Flyers defenseman Andrew MacDonald, toppling MacDonald like a bowling pin into Mason and snapping Mason's head backward against the Consol Energy Center ice, Mason took two baseline exams on the same day to help determine the concussion's severity. "You're circling numbers on a piece of paper from 1 to 10 on how you feel," Mason said. "How do you know from 1 to 10?" He failed the test both times.

On April 17, the morning of Game 1 of the Rangers series, with Berube having already announced that Ray Emery would start, Mason finally passed the baseline test, but he continued to experience symptoms. Upon finishing an hourlong skate and succession of goaltending drills at a Chelsea Piers rink the next day, he removed his mask to reveal a ghostly pallor. He would be fine for his first 10 minutes of practice, he said, but then, as the workout neared its end, he'd feel like throwing up.

Emery started Game 2. The Flyers won. All the while, Mason said, he wanted to play, but Berube and goaltending coach Jeff Reese refused.

"They did everything that they could to prolong me from coming back so they could make sure when I was back I was 100 percent healthy," Mason said.

"You sit on the couch, and all you do is watch TV, and even that bothers you. You sit on the couch getting stir crazy and depressed because you're not playing hockey, especially come playoff time. You miss the first game. You miss the second game. You miss the third game. And that's when it really starts to piss you off."

On the day of that third game - April 22, 10 days after he'd been concussed - Mason told Berube and Reese after the Flyers' morning skate that he felt normal again, that he wanted to go through the routine of suiting up for a game, even if he didn't play. Late that afternoon, the Flyers, through their Twitter account, announced that Mason would dress as Emery's backup, and when asked whether Mason was totally healthy, Berube said: "Yeah."

"The most important thing is the player's health and safety first and foremost - with me, anyhow," Berube said Friday. "If I had a little bit of doubt in my mind about a guy going in with that, he wouldn't go in."

Berube left unexplained what he would have done had Emery been injured early in Game 3 or why, if Mason was healthy enough to replace Emery for the game's final 7 minutes, 15 seconds, he wasn't healthy enough to start. But then, that's the ethical tangle that concussions can cause.

Thanks in large part to Emery's subpar performance in Game 3, the Flyers were trailing in the series ahead of Game 4. So Mason lay on that table as a trainer massaged his neck and inserted those sterilized needles into his head. The pain and pressure vanished. They didn't return after the morning skate, and this time, with the Flyers' season in the balance, Craig Berube wasn't going to stop his No. 1 goaltender from playing.

Steve Mason is 25 years old, and he said this concussion was his third and his most severe. He was asked Friday if he had read up on any of the recent research about concussions and their long-term effects on the brain. His response: "I don't do much reading. . . . If I was still feeling [symptoms], and I wasn't able to come back and play, then I'd start worrying."

No one asked the obvious follow-up. There was no need to. Was it worth it? Steve Mason's answer would have been yes. At this stage of his career, for so many pro athletes in his position, the answer will always be yes. Here's hoping that the question doesn't someday come to haunt him for the rest of his life.

@MikeSielski