A ‘whole new life’ at Riverview

It’s been almost one year since Philadelphia’s city-owned drug recovery home opened its doors. In that time, the city and its third-party healthcare providers have transformed the facility.

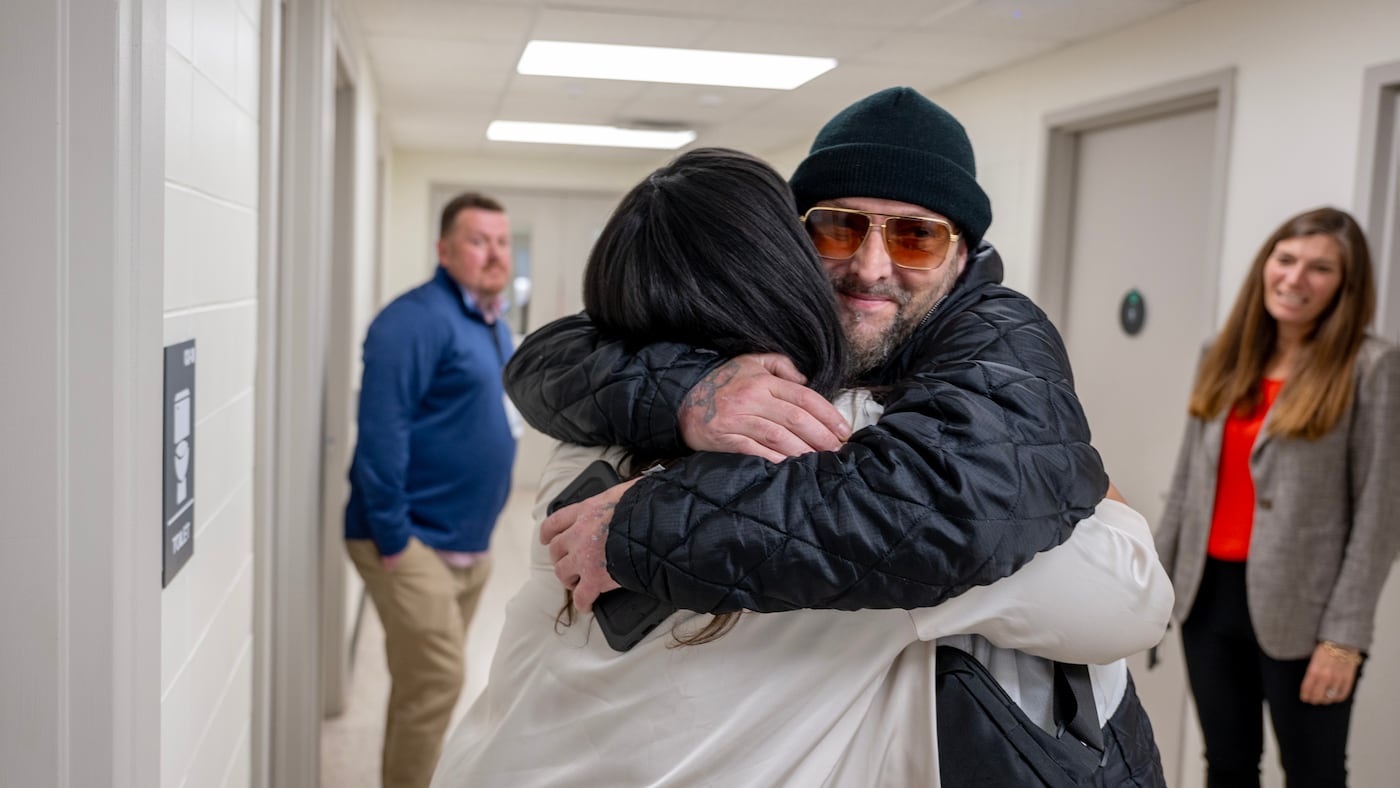

Kevin Bean was a frail 125 pounds last February when he entered a brand-new recovery house, a facility where he landed after spending four years in the throes of addiction — at times on the streets of Kensington, the epicenter of the city’s drug crisis.

The Frankford native was one of the first residents to enter the Riverview Wellness Village, the 20-acre recovery facility that Mayor Cherelle L. Parker’s administration opened in Northeast Philadelphia nearly a year ago as part of City Hall’s efforts to address opioid addiction and the Kensington drug market.

Bean, now 46 and boasting a healthier frame, just celebrated one year of sobriety and is preparing to move out of Riverview early next year.

He described his transition simply: “whole new life.”

Much of the mayor’s agenda in Kensington has been visible to the neighborhood’s residents, such as increased law enforcement and a reduction in the homeless population. But the operations and treatment outcomes at Riverview, located down a winding road next to the city’s jail complex, happen largely outside of public view. Last spring, some city lawmakers complained that even they knew little about the facility operations.

An inside look at the Riverview complex and interviews with more than a dozen residents and employees showed that, over the last year, the city and its third-party healthcare providers have transformed the facility. What was recently a construction zone is now a one-stop health shop with about 75 staff and more than 200 residents, many of whom previously lived on Kensington streets.

Those who live and work at Riverview said the facility is plugging a hole in the city’s substance use treatment landscape. For years, there have not been enough beds in programs that help people transition from hospital-style rehab into long-term stability. The recovery house industry has been plagued with privately run homes that are in poor condition or offer little support.

At its current capacity, Riverview has singularly increased the total number of recovery house beds in the city by nearly 50%. And residents — who are there voluntarily and may come and go as they please — have much of what they need on the campus: medical care, mental health treatment, job training, and group counseling.

They also, as of last month, have access to medication-assisted treatment, which means residents in recovery no longer need to travel to specialized clinics to get a dose of methadone or other drugs that can prevent relapse.

Arthur Fields, the regional executive director at Gaudenzia, which provides recovery services to more than 100 Riverview residents, said the upstart facility has become a desirable option for some of the city’s most vulnerable. Riverview officials said they aren’t aware of anywhere like it in the country.

“The Riverview Wellness Village is proof of what’s possible,” Fields said, “when we work together as a community and move with urgency to help people rebuild their lives.”

While the facility launched in January with much fanfare, it also faced skepticism, including from advocates who were troubled by its proximity to the jails and feared it would feel like incarceration, not treatment. And neighbors expressed concern that the new Holmesburg facility would bring problems long faced by Kensington residents, like open drug use and petty theft, to their front doors.

But despite some tenets of the mayor’s broader Kensington plan still facing intense scrutiny, the vocal opposition to Riverview has largely quieted. Parker said in an interview that seeing the progress at Riverview and the health of its residents made enduring months of criticism “well worth it.”

“I don’t know a Philadelphian who, in some way, shape, or form, hasn’t been touched by mental and behavioral health challenges or substance use disorder,” said Parker, who has spoken about how addiction shaped parts of her own upbringing. “To know that we created a path forward, to me, I’m extremely proud of this team.”

Meanwhile, neighbors who live nearby say they have been pleasantly surprised. Pete Smith, a civic leader who sits on a council of community members who meet regularly with Riverview officials, said plainly: “There have been no issues.”

“If it’s as successful as it looks like it’s going to be,” he said, “this facility could be a model for other cities throughout the country.”

Smith, like many of his neighbors, wants the city’s project at Riverview to work because he knows the consequences if it doesn’t.

His son, Francis Smith, died in September due to health complications from long-term drug use. He was 38, and he had three children.

Getting a spot at Riverview

The sprawling campus along the Delaware River feels more like a college dormitory setting than a hospital or homeless shelter. Its main building has a dining room, a commercial kitchen, a gym, and meditation rooms. There are green spaces, walking paths, and plans for massive murals on the interior walls.

Residents live and spend much of their time in smaller buildings on the campus, where nearly 90% of the 234 licensed beds are occupied. The city plans to add 50 more in January.

Their stays are funded through a variety of streams. The city allocated $400 million for five years of construction and operations, a portion of which is settlement dollars from lawsuits against pharmaceutical companies that manufactured the painkillers blamed for the opioid crisis.

To get in to Riverview, a person must complete at least 30 days of inpatient treatment at another, more intensive care facility.

That is no small feat. There are significant barriers to entering and completing inpatient treatment, including what some advocates say is a dearth of options for people with severe health complications. Detoxification is painful, especially for people in withdrawal from the powerful substances in Kensington’s toxic drug supply.

Still, residents at Riverview have come from more than 25 different providers, according to Isabel McDevitt, the city’s executive director of community wellness and recovery. The bulk were treated at the Kirkbride Center in West Philadelphia, the Behavioral Wellness Center at Girard in North Philadelphia, or Eagleville Hospital in Montgomery County.

They have ranged in age from 28 to 75. And they have complex medical needs: McDevitt said about half of Riverview’s residents have a mental health diagnosis in addition to substance use disorder.

She said offering treatment for multiple health conditions in one place allows residents to focus less on logistics and more on staying healthy.

“Many of the folks that are at Riverview have long histories of substance use disorder, long histories of homelessness,” she said. “So it’s really the first time a lot of people can actually breathe.”

When new residents arrive, they go through an intake process at Riverview that includes acute medical care and an assessment for chronic conditions. Within their first week, every resident receives a total-body physical and a panel of blood work.

“They literally arrive with all of their belongings in a plastic bag and their medications and some discharge paperwork,” said Ala Stanford, who leads the Black Doctors Consortium, which provides medical services at Riverview. “We are the ones who greet them and help get them acclimated.”

Stanford — who this fall announced a run for Congress — said doctors and nurses at Riverview have diagnosed and treated conditions ranging from drug-related wounds to diabetes to pancreatic cancer. And patients with mental health needs are treated by providers from Warren E. Smith Health Centers, a 30-year-old organization based in North Philadelphia.

Residents’ schedules are generally free-flowing and can vary depending on their wants and needs. About 20% have jobs outside the campus. Culinary arts training will be available in the next month or so. And residents can meet with visitors or leave to see family at any time.

They also spend much of their time in treatment, including individual, family, and group therapy. On a recent day, there were group sessions available on trauma recovery, managing emotions, and “communicating with confidence.”

Vernon Kostic, a 52-year-old Port Richmond native who said he has previously been homeless, has been in and out of drug treatment facilities for years.

He said he’s been content as a Riverview resident since July, and called it “one of the smartest things that the city has ever done.”

“We have the doctor’s office right over here,” he said. “They’ve got counseling right here. Everything we need. It’s like a one-stop recovery place.”

Finding ways to stay at Riverview

Finding success in recovery is notoriously hard. Studies show that people who stay in structured sober housing for at least six months after completing rehab see better long-term outcomes, and Riverview residents may stay there for up to one year.

But reaching that mark can take multiple tries, and some may never attain sobriety. McDevitt said that on a monthly basis, about 35 people move into Riverview, and 20 leave.

Some who move out are reunited with family and want to live at home. Others simply were not ready for recovery, McDevitt said, “and that’s part of working with this population.”

Fields said a resident who relapses can go back to a more intensive care setting for detoxification or withdrawal management, then return to Riverview at a later time if they are interested.

“No one is punished for struggling,” he said. “Recovery is a journey. It takes time.”

“If it’s as successful as it looks like it’s going to be, this facility could be a model for other cities throughout the country.”

Providers are adding new programming they say will help residents extend their stays. Offering medication-assisted treatment is one of the most crucial parts, said Josh Vigderman, the senior executive director of substance use services at Merakey, one of the addiction treatment providers at Riverview.

In the initial months after Riverview opened its doors, residents had to travel off campus to obtain medication that can prevent relapse, most commonly methadone and buprenorphine, the federally regulated drugs considered among the most effective addiction treatments.

Typically, patients can receive only one dose of the drug at a time and must be supervised by clinicians to ensure they don’t go into withdrawal.

Vigderman said staff suspected some residents relapsed after spending hours outside Riverview, at times on public transportation, to get their medication.

This fall, Merakey — which was already licensed to dispense opioid treatment medications at other locations — began distributing the medications at Riverview, eliminating one potential relapse trigger for residents who no longer had to leave the facility’s grounds every day.

Interest in the program has been strong, Vigderman said, with nearly 80 residents enrolling in medication-assisted treatment in just a few weeks. Merakey is hiring more staff to handle the demand.

What’s next at Riverview

The city is eying a significant physical expansion of the Riverview campus, including a new, $80 million building that could double the number of licensed beds to more than 500. That would mean that about half of the city’s recovery house slots would be located at Riverview.

Development and construction of the new building, which will also house the medical and clinical facilities, is likely to take several years.

Parker said the construction is “so important in how we’re going to help families.” She said the process will include “meticulous design and structure.”

“The people who come for help,” she said, “we want them to know that we value them, that we see them, and that we think enough of them to provide that level of quality of support for them.”

In the meantime, staff are working to help the center’s current residents — who were among the first cohort to move in — plot their next steps, like employment and housing.

That level of support, Vigderman said, doesn’t happen in many smaller recovery houses.

“In another place, they might not create an email address or a resumé,” he said. “At Riverview, whether they do it or not is one thing. But hearing about it is a guarantee.”

Bean is closing in on one year at Riverview. He doesn’t know exactly what’s next, but he does have a job prospect: He’s in the hiring process to work at another recovery house.

“I’m sure I’ll be able to help some people,” he said. “I hope.”