What’s so ‘magic’ about the secret South Jersey mud rubbed on baseballs? These Penn researchers think they know why.

The World Series, like the regular season, will use baseball mud that "spreads like cream and grips like sandpaper."

The Phillies’ World Series quest is over, but to hear Doug Jerolmack tell it, the Philadelphia area will nevertheless play a vital role on baseball’s biggest stage.

The University of Pennsylvania scientist is talking about our mud.

Grayish-brown, goopy “magic” mud from the banks of a Delaware River tributary in South Jersey, with properties so precious that its purveyors refuse to divulge the exact location.

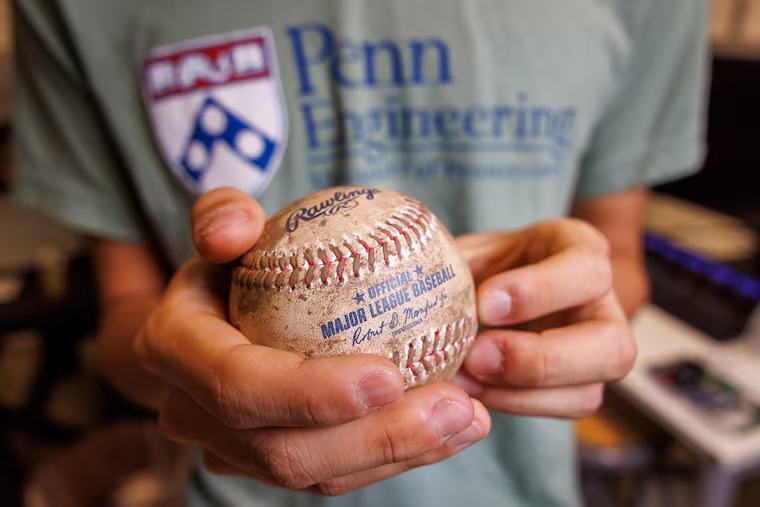

Hard-core fans know that Major League teams have long been rubbing this New Jersey mud on their baseballs before every game, removing the gloss on the white leather so that pitchers can get a better grip. It’s the only product approved by the league for that purpose, prized because it spreads in a uniform, thin layer with just the right amount of grit.

Jerolmack, a geophysicist and mechanical engineering professor at Penn, is digging deeper. He and his colleagues have been studying samples of the mud in their lab, and so far the results have been a surprise.

Under a microscope, the material looks like ordinary mud — a mixture of sand, silt, clay, and water. But when the scientists tested it with a rheometer, a device that measures viscosity, they found it behaved more like a fine face cream. The more force they applied, the thinner it spread.

Ordinarily, a substance containing this much sand would not spread so thin and smooth, Jerolmack said. But the baseball mud, sold in jars by the Bintliff family of Longport, N.J., seems to have the best of both worlds — perhaps because of some microbial secretion they have yet to identify.

“It spreads like cream, and it grips like sandpaper,” he said.

Bigger than baseball

Jerolmack gave a tour of his lab Thursday, as fans were still reeling from the Phillies’ defeat in the National League championship series. No joy in this particular Mudville, to quote the old-time baseball poem, but he said the mud research must go on.

That’s because it is now about something bigger than baseball.

It all began in 2019, when Jerolmack was asked by a sports journalist to analyze a sample of the mud. He did some preliminary analysis of the material and found little to explain its unusual properties. But he was intrigued, surmising that if he could unlock the material’s secrets, he might be able to make a version of his own.

Fear not, baseball purists. Jerolmack said he and his colleagues are not out to compete with the product used by Major League Baseball. Called Lena Blackburne Original Baseball Rubbing Mud, it is named for a coach on the Philadelphia A’s who discovered the secret riverbank source in 1938, and the league has been using it ever since.

“I’m not doing this to put the magic mud people out of business,” the scientist said.

Instead, he thinks that a substance with these properties might have applications beyond sports — perhaps as an industrial lubricant.

Jerolmack joined forces with Paulo Arratia, a Penn professor of mechanical engineering, and the pair enlisted post-doctoral researcher Shravan Pradeep to perform a battery of tests on the baseball mud.

First, Pradeep added a chemical agent to the mud to unstick all of its clay particles from each other, then separated them further by blasting the material with ultrasound. Next, he used a laser-equipped device to measure the size of those particles as well as the larger grains of sand.

At first, nothing remarkable stood out.

“It pretty much looked like mud from other places,” Jerolmack said.

The team then measured the material’s viscosity, quantifying a property called “shear-thinning” — its ability to spread in ultra-thin, creamy-smooth layers. The mud’s performance was a home run, Jerolmack said, akin to that of some of the most expensive face creams.

Yet despite its creaminess, the mud also gives the baseball a sufficiently gritty feel. The team measured the frictional forces between the mud and a custom-built, synthetic “finger” to simulate the grip of a human hand.

The analysis is still underway, but the researchers suspect that some additional ingredients are contributing to the mud’s properties, perhaps organic substances produced by decaying plant matter. They’ve started trying to make versions of the mud in the lab, adding various components to see if they can replicate what is found in nature, Arratia said.

“Somehow nature found a way to put them together to have these special properties,” he said.

Baseball protocol

Major League Baseball also has explored using alternative versions of the mud, concerned about the consistency of the product applied to its baseballs. The league has even tested balls treated with a Dow Inc. chemical additive.

A league spokesman declined to comment. But for now, the Blackburne mud is the only league-authorized ball-deglossing material, and it must be applied with a specific protocol. According to ESPN, the approved technique involves “painting” mud on the ball’s surface with two fingertips, then rubbing it between both hands to work the mud into the pores of the leather.

Other foreign substances are off-limits, though some pitchers have nevertheless broken that rule — secretly “doctoring” the ball with a sticky material to get an even better grip. The tighter the grip, the faster pitchers can spin the ball as it leaves their fingers, causing it to curve in a deceptive manner.

Jerolmack is not a big baseball fan, but he is fascinated by all the attention paid to the baseball mud.

His usual area of study involves the flow of earthen materials on a much larger scale — think mudslides, erosion, and sand dunes. Earlier this month, he was at Corson’s Inlet on the Jersey Shore, measuring the mechanical properties of the soil where it transitions from the muddy bayside to the sandier beach to the east.

But when he tells his Philly-area friends about his research, the baseball mud project is the one they always ask about.

And this week, when the Phillies failed in their bid to return to the World Series, he shared the region’s communal pain.

“I’m a Philadelphian,” he said. “So my heart still breaks.”