The Sixers and Comcast Spectacor should start the conversation to bring a single sports hall of fame and museum to Philly

Philadelphia is the best sports city in America. It’s a crime there isn’t such a place already.

Somewhere within the duel that could help define Philadelphia’s future, between the 76ers’ push to build themselves a new arena at Market East and Comcast Spectacor’s plan to pour more than $2 billion into reshaping the South Philadelphia sports complex, there’s a hole in the city that should be filled.

Philadelphia ought to have a sports hall of fame and museum in a single location, a mini Cooperstown or Canton, and the public debate over the Sixers’ arena proposal provides the perfect platform to raise and consider the idea again.

Lou Scheinfeld, formerly the Flyers’ founding vice president and the CEO of the Sixers, has made a sports museum a passion project for more than a decade now. The Philadelphia Sports Hall of Fame has been around since 2004 but has never had a must-visit home.

Any discussion about whether the city would be better off with a new arena/concert venue at 10th and Market or a hospitality/retail complex at Broad and Pattison ought to include another discussion: one about the creation of a place to honor the best and most memorable figures and moments in Philadelphia sports history — the pro teams, the Big Five, high school sports, boxing, rowing, more.

This is the best sports city in America. It’s a crime there isn’t such a place already.

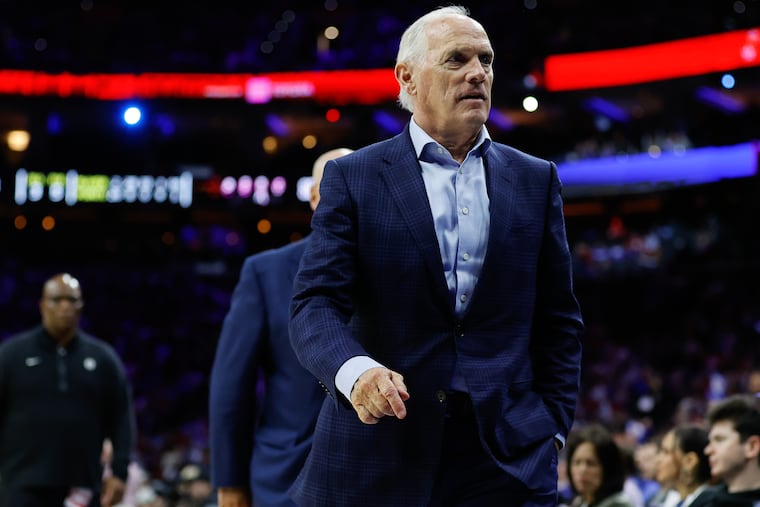

Scheinfeld has spoken to Dan Hilferty, Comcast Spectacor’s chairman and CEO, about the possibility. The best way to characterize Hilferty and Comcast Spectacor’s position on the matter is this: desirable but aspirational.

“We would love to be part of the discussion,” Hilferty said Wednesday in an interview, “and we would like to figure out together how to make the economics work and position the museum as a place you wouldn’t want to leave.”

No one should be naive enough to think that Hilferty and Comcast Spectacor don’t have multiple motives in endorsing the idea and floating the South Philadelphia complex as a potential site. Coming out in favor of a museum/hall of fame is a smart move in their public-relations battle with the Sixers.

For their part, though, the Sixers themselves aren’t necessarily opposed to the idea — preferably on their terms and turf. Ken Avallon, the president of the Philadelphia Sports Hall of Fame, said that he has reached out to co-owner David Adelman and the team about the prospect of including the hall in the Market East arena plan but that the idea isn’t top of mind for them.

“It’s not like they’ve ignored us,” Avallon said. “They’ve responded, but there’s nothing imminent. It’s, ‘We’re interested, and it’s not a priority.’ And I can’t blame them, with everything they’re dealing with down there.”

Clearly, there are gaps to be bridged here — not just between the Sixers and Comcast Spectacor, but between the museum’s backers and the Hall’s. Scheinfeld had targeted the old Jetro warehouse on 11th Street, right across from Lincoln Financial Field, as the spot for the museum.

Though two of the driving forces behind the idea — Ed Snider and Lewis Katz — had died, in 2018 Scheinfeld secured the zoning rights to open the museum there. He had a collector, Nicholas DePace, a South Jersey cardiologist, whose archive of memorabilia was valued at more than $35 million. He had a board of advisers — Ed Rendell, Harold Carmichael, and former La Salle and Temple athletic director Bill Bradshaw among them. He needed $4 million to open.

But the previous Comcast Spectacor administration, Scheinfeld said, told him, We want to own and operate everything down here. “There was a movement to keep us out,” he said. His attempts to find other benefactors failed. Aren’t the teams paying for this? We don’t give money to sports. We give money to children with cancer. The pandemic hit. He couldn’t get an angel investor. The momentum faded.

“We lost the lease. We lost the money. And I lost heart,” Scheinfeld said.

» READ MORE: Sixers will limit game-day closures of 10th and 11th Streets at proposed downtown arena

What’s more, Scheinfeld and Avallon years ago had discussed joining forces. To say it didn’t work out is putting it mildly.

“It’s the opposite of joining forces,” Avallon said. Their timelines didn’t align at all. “We don’t want to take it slow,” Scheinfeld said. “We need to have the baby.” Avallon was more conservative in his approach. “Any numbers we’ve put together include an operational endowment,” he said, “which covers literally three years of expenses if you don’t have a single paying customer.”

The Hall’s modest collection of memorabilia resides at Spike’s Trophies, on Grant Avenue in the Northeast. “We haven’t taken on any loans for the effort,” Avallon said. “We haven’t even solicited for a museum.”

Funding will of course be an issue for such a project, perhaps the biggest one. The Western Pennsylvania Sports Museum, in Pittsburgh’s Strip District, is marvelous: interactive exhibits, multiple floors, a souvenir and vintage apparel store. It’s also part of the larger John Heinz History Center, which is an affiliate of the Smithsonian Institution.

And if a museum/hall of fame did exist here, what site would be best for it? South Philadelphia would seem logical, given it’s the four teams’ home now. But Phil Laws, the president of the Wells Fargo Center, acknowledged that he thinks of a sports museum in the same way that he does the retail establishments that Comcast Spectacor wants to build at the complex — as an amenity, not as a revenue-driver. “It’s something to do while you’re down here,” he said.

A cleaned-up and revitalized Market East, meanwhile, would theoretically provide the measure of foot traffic that could allow the museum to attract consistent crowds even on nongame days. The proximity to the Pennsylvania Convention Center would be another potential draw.

“That was one of the reasons we diverged from Lou,” Avallon said. “His idea was that you have so many thousands of people coming through on game days, and they’ll walk through the museum. We just didn’t see it that way.

“We’ve been to enough home games to know: You either want to tailgate or go to the game. Most people are not going to spend an hour and a half paying money to see a museum.”

Hilferty said he had been unaware of the distance between Scheinfeld’s and Avallon’s visions. “But,” he added, “if we could be part of bringing everybody together, that would be exciting to me.”

It should be exciting for everyone in the Philadelphia community: the Eagles, the Phillies, the colleges and universities, the philanthropists and power people who can make it happen, the fans and families and tourists who would stream through the doors. This is a project worth pursuing. This is a conversation worth starting and having. Let’s have it.