‘The right to miss’: How Dr. J changed video-game history and paved the way for Madden

On the heels of his 1983 NBA title 40 years ago, Julius "Dr. J" Erving sat down with EA Sports to discuss "Dr. J and Larry Bird go One on One." The game would revolutionize the genre.

One in a series of stories remembering the 1982-83 76ers, one of the NBA’s best teams ever.

He bent a wire hanger into the shape of a basketball hoop, hung it over his bedroom door, and ran the hallway with a tennis ball before slamming it home. A teenaged Trip Hawkins, just like most kids in the 1970s, fell in love with Julius Erving, who played in the flashy ABA, wore cool sneakers, had an afro, and seemed to know how to fly.

“I just wanted to be him,” Hawkins said.

And there he was, a decade later, in the conference room of Electronic Arts — the video game company Hawkins launched months earlier near San Francisco — sitting across from Dr. J.

The company eventually became a juggernaut behind the John Madden football series. But EA had yet to make a sports game, and they still were trying to find their way.

Hawkins convinced his boyhood idol in 1982 to be the face of the basketball game the company planned to release a year later. Erving, after receiving some shares in the company, was in and convinced Larry Bird to follow.

The game — Dr. J and Larry Bird go One on One — was a success after being released in 1983 and helped solidify EA’s place 40 years ago as a major player in the market. It signaled to Hawkins that sports video games could be more than just the personal project he thought they were when he wrote his company’s initial business plan.

Five years later, Electronic Arts released the first Madden game, revolutionizing the genre with a line of “EA Sports” titles and leading a Hall of Fame football coach to became best known for a video game.

First, they had to make One on One. The company’s staffers peppered Erving in that conference room with questions, hoping to glean some details that could make their basketball game authentic. How would you defend Larry? When’s the best time to release a jump shot? How often would you make a shot from here? How about if you had a hand in your face?

It depends, Erving said. Depends on what?

“He said, ‘Have I earned the right to miss,’” Hawkins said. “He was like a Buddhist monk at the top of the mountain telling me the secret. Have you earned the right to miss?”

‘Ambassador of basketball’

Hawkins originally planned for EA’s first sports entry to be a football game, as the 49ers fan dreamed of featuring Joe Montana and Dwight Clark after leaving his job at Apple Computers around the time of “The Catch.” But Montana had a deal with Atari, so football — “If he’s not going to do it, then I don’t want to do it,” Hawkins said — was out.

He pivoted to basketball, recalled a one-on-one tournament he watched on TV in the early 70s, and decided it would make a good game. But who would be the players? An athlete had never been in a video game — Atari’s 1981 soccer game was named for Pelé, but he was not a playable character — so Hawkins went straight for the top.

There was no bigger star than Dr. J, who led the Sixers to the 1983 NBA title months before the game was released. He still was the NBA’s top draw as Bird and Magic Johnson were just entering the league, and Michael Jordan still was in college.

“I always thought of Julius as the ambassador of basketball,” Hawkins said. “Dr. J really became the first human being to make a deal to appear in a game.”

Hawkins connected with Erving, met him in Las Vegas, and sold him on his vision. He offered him $25,000 plus a 2.5% cut of the royalties. Hawkins, knowing the impact Dr. J would have, sweetened the deal by offering him shares in EA. Bird didn’t get the same offer, and Hawkins never made it again, not even to Madden.

“It’s still in my portfolio all these years later,” Erving said.

“Smart man,” Hawkins said.

With Erving secured, EA needed to find his opponent. Bird was an easy choice after the Sixers and Celtics played in three straight conference finals. The two were the only playable characters in the game, and that was plenty. A year after One on One was released, Bird and Erving fought during a game. They were perfect foils.

“We always had a lot of respect for one another,” Erving said. “But on the court, once you got within the black lines, he was the enemy. There was no question about it. We always said, ‘If your mother comes out there, she better be ready to take an elbow.’”

‘What am I doing with these nerds?’

Erving soon flew to EA’s offices in San Mateo, Calif., to play basketball at a YMCA and meet the staff. They wanted to take pictures of Dr. J in action, hoping they could best replicate it on the 8-bit Apple II machine. And then they met with him in that conference room.

“He was really fun to talk to,” said Eric Hammond, the game’s 19-year-old programmer. “He didn’t have that superstar ego, and he was a real guy. He was so gracious. Back then, I idolized him. It was like this guy isn’t just amazing, but he’s super cool.”

Hammond convinced his parents to buy an Apple II as a high school student in San Diego and released his first game just months after graduation. EA soon recruited him to create One on One and told him they planned to sign two NBA players for it. He was floored, Hammond said, to learn the two players were Erving and Bird.

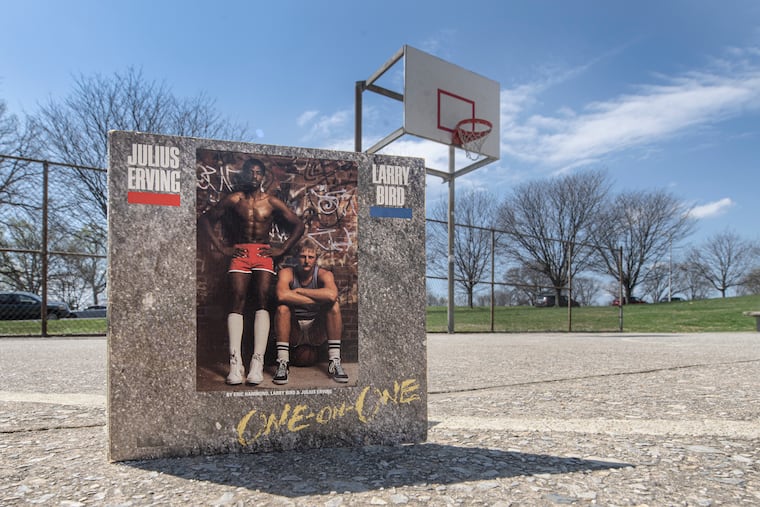

Hammond met Bird in the summer of 1982 after EA flew to Massachusetts to shoot the cover of the game, which featured the stars against a brick wall as if they just finished playing pickup. Hawkins considers it one of the best video game covers of all time but admits “there’s a little fatherly pride in there.”

And then they sat down with Bird.

“We had about a half hour in a closet. It was this tiny, little room,” Hammond said. “It was pretty clear that Larry was like, ‘What’s the minimum that I have to do to fulfill my obligations?’ He was there, but he wasn’t all that interested. It was like, ‘WTF? What am I doing with these nerds?’”

Hammond finished earlier games as fast as eight weeks but One on One was a different beast as the teenager pushed the limitations of what an Apple II could handle. Hammond spent the first part of the 18-month project at home before EA started to worry that the game would not be ready for Christmas of 1983. So EA moved Hammond north to an apartment in San Mateo before he asked if he could just work in the office.

“I pretty much lived at EA for the last two and a half months,” Hammond said.

A groundbreaking game

One on One now looks rudimentary, but 40 years ago, it was groundbreaking. Four years earlier, Atari released a one-on-one basketball game where the nets were lines and the ball was a square.

“There wasn’t a lot of video game action out there at that time,” Erving said. “There were some games, but they were very robotic. It wasn’t people moving, it was blocks and columns and triangles moving. This was a fun project.”

Hammond — who had his older brother, Greg, assist him with the graphics — created a tool to have Erving and Bird appear three times larger than characters in other video games. Their arms and legs moved, they jumped, and even resemble their real-life counterparts. There was a three-point line, a 24-second clock, and whistles for traveling and “hacking” fouls.

“There was a lot of pressure for him to deliver, and it was not an easy game to make,” Greg Hammond said. “They knew what they wanted in the game, and they had a pretty good design for it. He was responsible for making it happen.”

Hawkins pushed Hammond to find a way for the backboards to shatter after seeing Darryl Dawkins, Erving’s teammate on the Sixers, do it in a game. An angry janitor, inspired by a bit Hawkins saw as a kid on Rocky and Bullwinkle, sweeps up the shards as play stops.

“Whenever you saw a real backboard get shattered, you could tell that it made an incredible mess and took a long time to clean it up,” Hawkins said.

Knowing the game would be mostly played on the Apple II by one player, Hammond spent hours trying to make the computer opponent good enough to keep the game entertaining. The game had four difficulty levels ranging from “park and rec” to “pro.”

“The hardest thing of the project was the AI,” Eric Hammond said. “I’m trying to get the computer player scalable so it would be easy and hard but also not stupid. It had to be smart but not too smart. One 19 year-old kid trying to do all this stuff.”

And as he was finishing production, Hammond thought back to the “polar opposite” experiences he had with the game’s two stars.

“I kind of favored Dr. J in the coding,” said Hammond, who would become a vice president at SEGA in the 1990s and oversee the U.S. launch of the Dreamcast console.

The right to miss

Erving explained to his audience in that conference room how a jump shot is best released at the moment just before the shooter begins to fall back to the ground. He talked about the art of the dunk and how he would try to stop Bird. It all was intel infused into the game. But Hawkins needed to know what Erving meant by “the right to miss.”

“If I come down the floor the last three times and I’ve made three shots in a row, my teammates know that I’m in a flow. They know that I’m loose, that I’m hot, and they want to give me the ball,” Erving told him. “The defense knows that they have to defend every possible thing I can do because now I’m willing to try almost anything because I’m feeling so good. For all those reasons, my shooting percentage is going to go up.”

Hawkins told himself in 1975 that it would take seven years for enough homes to have computers before a video-game company could be viable. He started EA in 1982 and soon had his first commercial success with One on One. After its first release on the Apple II, One on One was re-released over the next five years on eight consoles.

» READ MORE: Sixers needed Joel Embiid to be superhuman to beat the shorthanded Celtics. That doesn’t bode well.

It was a hit — “I was getting royalty checks for $180,000. It was just weird,” Hammond said — and a breakthrough as Hawkins said it “showed the world that we can make one of the best selling things there is in our category.” What was once just two sentences in a business plan became a pillar of the company.

“What Dr. J and Larry Bird really brought forward were the personalities of the athletes, which we had not seen before,” said Matthew Thomas Payne, a video game historian and associate professor in Notre Dame’s department of film, television, and theatre. “It’s about harnessing the stardom of these athletes. They were hip and topical. What athletes do for video games is they make them freaking cool. Maybe geek culture wasn’t what it was in the 80s and now it’s geek chic.”

A year later, Hawkins convinced John Madden to help EA make a football game. It took four years — “They were calling it Trip’s folly,” Hawkins said — but Hawkins was adamant that the game would be finished. The production was complicated as Madden insisted that his game featured 11 players on each team just like the real thing.

It didn’t seem like the 8-bit Apple II could handle it, but Hawkins — knowing the market that existed in sports games — kept pushing.

The first Madden was released in June 1988 on the Apple II and was followed two years later on the 16-bit Sega Genesis. The game has been released every year since, selling more than 130 million copies and grossing more than $4 billion. The Madden series turned EA from an unknown start-up — “Who the hell is Electronic Arts,” Hammond said he thought when they first contacted him — to a powerhouse. And it may have never happened without Dr. J.

“I think it’s fair to say that,” Hawkins said. “But I don’t really think that’s true. I was so determined. What the Dr. J game gave me was the right to miss.”

» READ MORE: P.J. Tucker’s shot making comes alive in Sixers’ win over Celtics: ‘We don’t win that game without him’