An AAU coach dies, leaving a large (and tall) following | Mike Jensen

As word spread through the Philadelphia and wider basketball world that the long-time head of the Hunting Park Warriors AAU program, stricken with lung cancer, was in hospice, the visits picked up.

A nurse had to ask. All these men kept showing up at Greg Wright’s room. It wasn’t unusual for people to visit cancer patients in their final days. Some family, a few friends, small gatherings. But more and more kept showing up for this one room ... different people. Tall people.

“Is he an actor or something?”

Nope, the nurse was told, he never acted.

“He may not have had the Hollywood fame," Greg Wright Jr. said in early March, a few days after his father died on March 3, “but he had the people.”

As word spread through the Philadelphia and wider basketball world that Greg Wright, longtime head of the Hunting Park Warriors AAU program, stricken with Stage 4 lung cancer, was in hospice, the visits picked up.

“A lot of guys I’d never met until he was in the hospital," his son said. “Grown men came in weeping. It was definitely sad, but I saw the love. It made me proud.”

It got to the point, Wright’s close friend Rick Guillen said, that the security guards at the front of the cancer treatment center in the Feltonville section of the city would see maybe a couple of 6-foot-3 men walk in and just say, “You’re going to the second floor.”

“How did you know?”

“A wild guess.”

Not a surprise, either. Tennis Young, who had founded the program before turning it over to Wright, came in from Florida. Mike Green, once a star at Butler, came in from Europe. Mustafa Shakur from the West Coast. Whatever is the common stereotype of AAU coaches being the scourge of the sport, using kids for their own means, flip that on its head and you basically have Greg Wright.

I got to know him a little, more than a couple of decades back. If basketball was a way to enrich himself off the backs of his players, Wright missed that memo. He’d started with the Logan Police Athletic League, then moved to the Hunting Park program.

He was competitive, mind you. The Hunting Park Warriors weren’t usually the team you wanted to see in your bracket at the Donofrio in Conshohocken or the travel-team big time of Las Vegas. Wright always had talented ballplayers and knew what to do with them.

I once asked him about coaching the Morris twins.

“I used to mark the back of the shoes in the beginning," Wright said of telling Marcus and Markieff Morris apart. "I didn’t know who I was hollering at. I just put a triangle on Markieff’s shoe. … As they were running away [during practices], I could see who did what.”

I asked Wright in 2009 about the mileage on his Buick Park Avenue. Wright checked the odometer on his 6-year-old car; it had 164,412 miles.

Almost all basketball miles. In the offseason, Wright was all over the city for high school games, then moving out from there to see his old players in college.

“The last week, I saw maybe about 10 games,” said Wright, who worked for the city’s Department of Inspections. "I went from Villanova to Southern to Ben Franklin, all in one day, for high school games. Then we went to Temple for a game. The Temple-St. Joe’s game, I brought five guys.”

I hadn’t seen Wright in some years. He had handed over the Hunting Park Warriors program to Guillen, who still runs it and is a familiar presence on the local basketball scene. But nobody forgot this guy who never made it about himself.

His players showed up at Wright’s bedside and told stories.

A guy would turn the ball over.

“My fault, Unc.”

“It’s not your fault," Wright would say. “It’s my fault for having your dumb a— in the game.”

If every player didn’t turn out to be the Morris twins, Wright had understood this long before they did. He’d been a pretty good ballplayer himself at University City High. Even some who thought they’d make the NBA came to understand that Wright didn’t see them differently for falling short.

“I’ve been blessed to have so many brothers,’’ said Greg Wright Jr., now 40. “They may not have the same name or the blood flowing through them. I didn’t have a problem sharing my father. I was the lucky one. I was the one who called him my father for 40 years.”

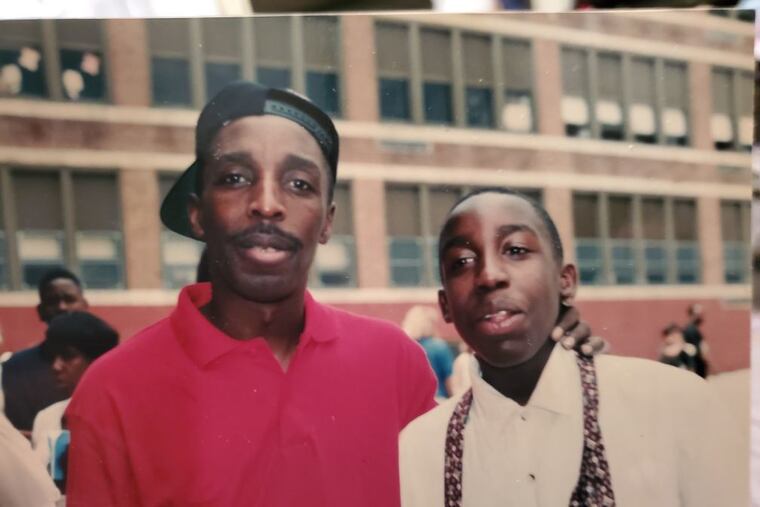

Tahric Gosley had lived with Wright for a time, sharing a bedroom with Greg Jr.

“I look at him like a dad. My dad was never there for me. He treated me just like his real son. For real,” Gosley said in 1998. "I go to him, talk to him about everything, not just basketball. Regular life things. He’ll give me an honest answer. We tell each other everything.”

Wright had been the one who got Gosley playing basketball. He ended up playing at Simon Gratz for Bill Ellerbee and Cleveland State for Rollie Massimino.

Greg Wright Jr. had played for his father, too.

“It took for me to be a grown man to understand this was his calling," Guillen said. “There’s a bunch of guys out here now that could use a Mr. Greg. He sacrificed so much of himself to help others. … Whatever life’s curveballs gave you, he gave you direction.”

What came through sounds universal …

“Taking care of your family, working hard,’’ Guillen said. “Not taking shortcuts.”

A last visit included a bedside discussion among basketball people. Guillen said. The discussion went on for quite a few minutes, Wright asleep in the bed. The discussion turned to a college ballplayer transferring. Suddenly, Guillen said, Wright was awake, wanted details.

“He always had the same style," Guillen said. “He never changed anything about him. We’re all going to carry him with us.”

Shakur had mostly played professionally overseas, instead of being the NBA star he probably expected he would become when he went out to Arizona as the top-ranked high school point guard in the country. But Guillen talked about how Wright was proud of what Shakur had turned into: a man now, in business in the Oakland area. Wright let Shakur know that.

“I really needed this," Shakur told Guillen about their visit.

“He knew everyone was coming," Guillen said. “He would smile, reach out, shake hands, tell them he loved them. Add something personal: How’s your father? His mind was sharp.”

Visits were still being lined up when Wright passed away at the age of 64.

It must be quieter at that front desk in Feltonville now.