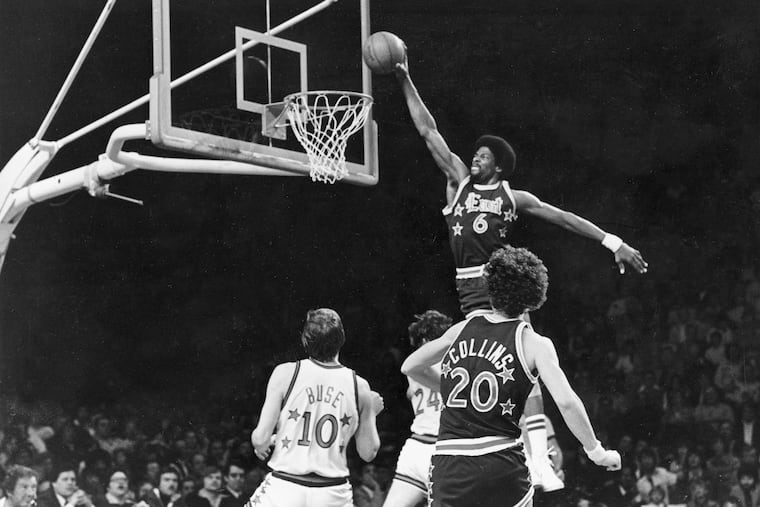

Dr. J, the first dunk contest, and the dawn of a new era for the Sixers and the NBA

In this excerpt from his book “Magic in the Air: The Myth, the Mystery, and the Soul of the Slam Dunk,” Inquirer columnist Mike Sielski details why the dunk contest was significant to Julius Erving.

Julius Erving will celebrate his 76th birthday on Sunday, just a few weeks after the 50th anniversary of the event that led to his milestone signing by the 76ers: the American Basketball Association’s Slam Dunk Contest. Erving’s victory in the five-man competition — held in Denver on Jan. 27, 1976, during the ABA’s final season, while he was starring for the New York Nets — marked his breakthrough into America’s sports and pop-culture consciousness.

In this excerpt from his book “Magic in the Air: The Myth, the Mystery, and the Soul of the Slam Dunk,” Inquirer columnist Mike Sielski details why the contest was so significant to Erving, to the Sixers, and to the evolution of professional basketball.

The people in charge of the ABA were under no illusions about the condition of their league as it entered its ninth season. Despite its star power — Connie Hawkins, George McGinnis, Erving, more — franchises were folding, or relocating then folding, every year. Two, the San Diego Sails and Utah Stars, went under during that 1975-76 season. Rather than committing to keep the league afloat, its top-drawing teams — the Nets, with Erving, and the Denver Nuggets, with their sky-walking star, David Thompson — were eyeballing the NBA, looking to bolt to a stabler, more lucrative situation.

To juice interest, and with less to lose with each passing day, the league’s decision-makers tried a new format for its midseason All-Star Game at McNichols Arena: The Nuggets, as the defending champions and the game’s hosts, would take on a squad of players picked from the ABA’s other six teams. That wasn’t all. The country-western singers Glen Campbell and Charlie Rich would perform before the game, and, at the suggestion of Jim Bukata, the league’s public-relations director, there would be a slam-dunk contest at halftime.

Five players, all of whom would already be in Denver for the game, would take part: Erving, Thompson, George Gervin, Artis Gilmore, and Larry Kenon. Including a non-All-Star in the contest would have required flying in a non-All-Star for the contest, and no one in the league was about to spend that extra money. Erving asked Kevin Loughery, the Nets’ head coach, if the contest ought to have a white participant, and in fact, the league invited the Nuggets’ Bobby Jones to compete. Jones declined. “I wanted to win the All-Star Game,” he told me. “I didn’t have the energy to do what those guys did.”

On Jan. 27, 1976, with 17,798 — the largest crowd in ABA history — on hand, with $1,200 in prize money at stake, the five competitors were briefed on the rules before commencing with the contest. Each of them could attempt up to five dunks in a two-minute span. One of the dunks had to be from a stationary position; one had to have the player start his move from the foul line, 10 feet away, or beyond. Two contestants would dunk on one basket and three would dunk on the other, the public-address announcer told everyone, “to take pressure off the rims and backboards.”

Based on “artistic ability, imagination, body flow, and fan response,” four judges would determine the winner. The panel: former Knicks star and Nuggets general manager Vince Boryla; Nuggets super-fan Alberta Worthington; high school standout LaVon Williams, who was “Mr. Basketball” in Colorado before heading off to the University of Kentucky; and Barry Fey, a former guard at Penn who, as a concert promoter, had set up the pregame festivities with Campbell and Rich.

Gilmore, the tallest competitor at 7-foot-2, appeared unsure of what to do, as if he hadn’t practiced or planned his dunks or was, for whatever reason, holding back. Gervin and Kenon were a little looser, but there was a mood of tentativeness in the arena until Thompson got the ball.

Fresh from a remarkable career at North Carolina State and in his rookie season with the Nuggets, he had been nervous throughout the days leading into the contest, so eager was he to live up to the home crowd’s expectations and hopes. His teammates had been pumping him up, encouraging him, letting him know which of his dunks they thought were his best. From the right side, he charged toward the hoop and hammered down a powerful right-handed slam. Working quickly, he ripped off a double-pump two-handed reverse and, from the left baseline, a 360-degree spin and jam, establishing himself as the man to beat.

But now, it was Erving’s turn. Standing directly under the basket, he dunked two balls at once — a nod, perhaps unconsciously, to his days at Roosevelt High School on Long Island, when he pulled off the trick as a teenager. Then he walked out to halfcourt, then back to the free-throw line, then back to the opposite free-throw line, counting and measuring his steps as he went.

Before the contest, he had made a $1,500 bet with Doug Moe, then an assistant coach with the Nuggets, that he could take off from the foul line and dunk during his descent. He paused, bent at the waist, then started, a slight stutter step, then a sprint into four floor-eating strides from the midcourt stripe to just inside the foul line, then … whoosh. Up.

“I’ve described Julius as more of a glider than a jumper,” Jones told me. “He was more of a long jumper.”

The crowd let out a communal Whoa. Erving lost the bet to Moe, but he didn’t need another dunk to win the contest. After a reverse from the right side, he swooped in from the left side, grabbing the rim with his left hand and windmilling the ball through the hoop with his right, then finishing with an “Iron Cross” dunk from the right baseline, spreading his arms and dunking the ball without looking at the basket. All the game’s players greeted him at halfcourt to congratulate him. The judges’ decision was a formality.

“It was something else,” Erving told me. “It’s still talked about today. I didn’t know it would have such a lasting effect on basketball history, and neither did any of the other players. I don’t think any of us really knew. We were the ABA, and we were crowd-pleasers. Yes, we made history, but the intention wasn’t making history.”

The All-Star Game — and, in turn, the dunk contest — was supposed to have been broadcast nationally but ended up being televised in just five markets: Denver, Indianapolis, Louisville, San Antonio, and St. Louis. Since the game didn’t end until after 2 a.m. Eastern time, the ripples from the contest didn’t start spreading immediately. Only after Good Morning, America and The Today Show featured Erving and Thompson did the magnitude of the event begin to reveal itself.

“Merger plans had long been in the works between the ABA and the NBA,” ESPN’s Eric Neel once wrote, “but the contest no doubt hastened them.”

Afterward, Erving said that he was unlikely to compete in another dunk contest ever again, that his knees were “75 percent of what they used to be.” (He did, in fact, compete in another: the NBA’s 1984 contest, where he finished second to the Phoenix Suns’ Larry Nance.) But he and the ABA had already ignited, or at least accelerated, an insurrection within pro basketball. The slam dunk was cool, and the ABA had embraced it, which made the ABA cool, which made the NBA seem stuffy and stiff in comparison, mostly because it didn’t have the athlete who, more than anyone, had made the slam dunk cool.

In Philadelphia, 76ers general manager Pat Williams had watched those TV highlights of the contest.

“That,” he told me, “is what really put Julius on the stage.”

Erving never missed a game during his three-year career with the Nets, leading them to the league championship in 1974 and 1976, and was at times seemingly too good to be true. Long before San Antonio Spurs coach Gregg Popovich figured out that he could scream at his franchise centerpiece, Tim Duncan, and that Duncan would take the criticism without complaint, and that the other, lesser players would understand Popovich gave the team’s superstar no special dispensation, Kevin Loughery used the same psychological tactic with Erving. Doc messed up, even when he didn’t. Doc was no different, even if he was.

One night, Erving dunked over three defenders, and Loughery called a timeout for no reason other than to pull Erving aside and tell him, You just played the greatest three-minute stretch of basketball I’ve ever watched. Rod Thorn, an assistant under Loughery, had never seen a player catch and dunk an alley-oop pass with one hand until he saw Erving do it. The shame was that his exploits took place so often under the blanket of the ABA’s obscurity.

In Game 6 of the ‘76 ABA Finals, Erving scored 31 points, pulled down 19 rebounds, and blocked four shots as the Nets rallied from a 22-point deficit in the third quarter to beat the Denver Nuggets, 112-106, and win the series in six games. As they stormed the Nassau Coliseum court, Nets fans nearly trampled Nuggets’ play-by-play voice Al Albert, who climbed atop a table to escape. Albert lost his microphone and headset. The phone and cable lines he needed for his broadcast were cut. His television monitor crashed to the floor.

» READ MORE: Reflecting on the top 10 moments of Julius Erving’s career as he reaches 76 years old

The chaotic scene was a bittersweet valedictory for The Doctor’s tenure: The passion and adoration that he would earn over his career in the NBA, with the Sixers, would manifest itself in that final game … and never again with the Nets. Attendance was low throughout the ABA. So was revenue. The franchises were too regional. The league was falling apart.

“Everybody thought we were in the hinterlands,” Bill Melchionni, a member of that ‘75-75 Nets team, told me. “We were minor-league.”

Four ABA teams merged with the NBA in June 1976. “I can say without a doubt,” broadcaster John Sterling, who was the Nets’ radio play-by-play voice at the time, once said, “that what finally convinced the NBA to merge was a chance to get Julius in the league.” Melchionni, who had become the Nets’ general manager immediately after that championship series, began fielding phone calls from civic leaders and chambers of commerce around the country, begging to have Erving and the Nets come to their cities to play exhibition games, offering as much as $50,000 as enticement.

“We were scheduled to play two games in Vegas,” Melchionni told me. “Guys would ask, ‘How many minutes is he going to play?’ And I’d say, ‘It’s an exhibition game. He’s not going to play 48 minutes.’”

The calls stopped, of course, after Wednesday, Oct. 20, 1976. The last day that Julius Erving belonged to the ABA. The first day that the NBA belonged to Julius Erving.