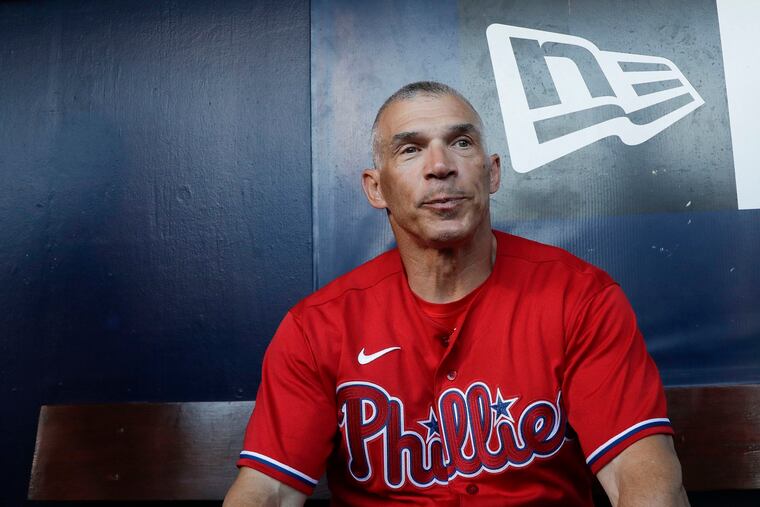

The Phillies’ John Middleton fired Gabe Kapler and hired Joe Girardi. Will it make a difference in the 2020 season?

Phillies ownership made a calculation that Girardi is good enough to bridge the roughly 10-win gulf between a .500 record and the postseason appearance that has eluded the franchise since 2011.

It was the last — if not the lasting — image from the Phillies’ 2019 season.

The final out had just been made. Players were still streaming off the field. But owner John Middleton left his suite, stood on the steps near the entrance to the dugout — in full view of cameras — and waited to shake manager Gabe Kapler’s hand.

Eleven days later, Middleton fired Kapler. Two weeks after that, he hired Joe Girardi. And nothing else the Phillies did in the offseason — not throwing $118 million at free-agent pitcher Zack Wheeler nor signing shortstop Didi Gregorius — carried more weight.

In replacing a manager who had a 161-163 record in two seasons at the helm with one who made the playoffs six times and won a World Series in 10 years with the New York Yankees, Middleton made his opinion clear: The manager matters. Maybe even as much as the makeup of the roster.

“People were telling me, ‘You had injury problems and you can’t blame Gabe for that,’” Middleton said in October. “But ultimately, I felt, if I was going to bring Gabe back, I had to be very, very confident we were going to have a different outcome in 2020. I couldn’t get confident enough that if I brought him back we wouldn’t run into other problems.”

It was a fair take. The Phillies did underachieve in going 81-81, their eighth consecutive nonwinning season — after Middleton green-lit half a billion dollars in player additions, no less.

But the managerial upheaval, at a time when the Phillies have a club-record payroll that is approaching the $208 million luxury-tax threshold, also raises reasonable questions. Over the course of a season — 162 games in normal times or 60 in the middle of a pandemic — how many wins and losses can be traced directly to the manager? In the absence of an equivalent to the WAR metric that is typically applied to players, and considering the myriad facets of the job, is a manager’s impact even measurable?

“I think managers are undervalued in baseball, to be honest,” said Phillies catcher J.T. Realmuto, who has played for five of them since 2014. “Just putting your players in the best position to succeed is not as easy as it seems.”

Middleton seems to concur. He made a calculation that Girardi — along with new pitching coach Bryan Price — is good enough to bridge the roughly 10-win gulf between a .500 record and the postseason appearance that has eluded the franchise since 2011.

Is he correct?

As with most things, it depends on who you ask.

» READ MORE: Joe Girardi’s many baseball stops prepared him to manage the Phillies

Making the grade

Bill James has a statistical formula for everything in baseball. But even the godfather of sabermetrics gave up long ago on trying to scientifically quantify a manager’s value.

“My contribution to the subject was to stop asking that question and shift to a different question: Not how good is this manager, but how does he manage?” James said. “What does one manager do that another does not? How much does he bunt? How many relievers does he use? How many different lineups does he use? By focusing on process questions, you can see some differences between one manager and another. If you focus on the question of whether a guy is good or bad, in my experience, you don’t really learn anything.”

Kapler has cultivated a reputation as a progressive thinker who is unafraid to push the bounds of baseball convention. He once summed up his managerial approach by saying, “We all need to challenge the [bleep] out of our own beliefs.” But his ideas on daily lineup construction, hitting philosophy, and bullpen management aren’t radical. Many are adopted from what has worked for other organizations. And for a franchise that had fallen far behind the analytical curve, Kapler’s data-driven method was appealing.

Girardi is big on data, too. Early in his Yankees tenure, he was ridiculed for carrying a binder chock full of trends and statistics. But you don’t last a decade in the manager’s office of the most scrutinized team in baseball without evolving. Girardi became known for blending new-school analytics with a traditional gut-feel. In particular, he excelled at wringing the most out of his bullpens with optimal deployment of relievers.

“He knows what he’s doing from the first pitch to the last out,” Phillies pitcher Jake Arrieta said. “He’s very good about handling a bullpen and understanding when it’s time to get the starter out of the ballgame. That’s something I really appreciate and I know the guys in the bullpen do, too.”

Said Realmuto: “Some managers go 100 percent off what the computer tells them; some managers go all off feel. Joe has a good understanding to be able to do both and not just do it because the piece of paper tells him.”

But does that translate to two wins per year? Five wins? More?

As former Phillies general manager Ruben Amaro Jr. sees it, the traditional 20-80 scouting scale for players (50 represents a solid regular; 70 is an all-star) can be applied to managers, too, with the grades loosely equating to a win total.

By Amaro’s admittedly subjective formula, a slightly above-average manager (50-55) can account for two or three wins in a 162-game season. A manager who is solidly above average (60-65) “probably gives you five to seven,” Amaro said. An all-star manager (70 or above) can win eight to 10 games.

“If it’s someone that fits not just the city but the personality of the team, he can make that much of a difference,” Amaro said, pointing to the Phillies’ 27-win improvement under Jim Fregosi from 1991 to 1993. “You can see that kind of turnaround.”

James tends to be more skeptical.

In the right situation, yes, he believes a manager can have a considerable impact. He cited Whitey Herzog, the St. Louis Cardinals’ longtime Hall of Fame manager, whose “small-ball” style maximized the offensive capabilities of Ozzie Smith, Lonnie Smith, Willie McGee, Tom Herr, Jose Oquendo, and others.

Generally, though, James believes a manager can only do so much.

“I think almost all managers make themselves obsolete after a year, two years, three years,” James said. “They solve the problems that they know how to solve. The ones that they don’t know how to solve fester and grow worse. Not many managers are able to continue to solve new problems in new situations.

“But there are certain times in a team’s history when a manager makes an immense difference in shaping the team. I think that if you study the history of any franchise, the moments at which managers come and go are almost always the obvious turning points.”

Middleton believes this is one of those moments for the Phillies. The roster is dotted with prime-age stars Bryce Harper, Realmuto, Aaron Nola and Wheeler; Rhys Hoskins and Scott Kingery are homegrown talents with upside; Adam Haseley, Alec Bohm, and Spencer Howard are touted prospects.

All they need is the right manager to bring them together.

Communication is key

There’s a degree of gravitas that comes with being one of only two managers since 1960 to survive at least 10 consecutive years in New York.

“He was the manager of the Yankees for how many years and had so many playoff seasons. That is something you can’t really replicate,” Realmuto said. “You can’t just make that up and say, ‘Hey, I’m a good manager. I’ve done this.’ He’s actually done it.”

Unlike Kapler, whose style and personality was never accepted by Philadelphia, Girardi will get greater benefit of the doubt after the first time he makes a pitching change that doesn’t work out.

But in-game strategy is only a fraction of a manager’s job. Amaro noted the importance of relating to the players and putting them in position for success. Charlie Manuel was a perfect example. Given his predilection for hitting and his ability to teach it, he matched up well with Phillies clubs that were built on offense from 2007 through 2010.

“Managing and coaching is really about interpersonal relationships,” Amaro said. “It’s not necessarily about the Xs and Os because most of the Xs and Os take care of themselves over time.”

Girardi has gotten positive reviews from within the clubhouse for his preparation and communication. It helps that he doesn’t have to win players’ respect.

“He’s big on having those conversations to build that connection,” Arrieta said. “All good managers do that. Joe has been doing it for a long time.”

But how much closer does that get the Phillies to a playoff spot? They finished eight games out of the second wild-card spot last season. Can Girardi bridge that gap?

“I don’t know the players as well as some other people know them,” Amaro said, “but I know the city. And honestly, Joe Girardi — and I know Bryan Price and I know [bench coach] Rob Thomson a little bit — with those three guys at the helm, I do believe they’re the right guys and the right fit for this city and this group.”

That’s precisely the calculation that Middleton made last October.