The Whittler and The Writer: How Gary Smith wrote the definitive piece on John Chaney | Mike Sielski

In 1994, Smith went back to his Philly stomping grounds for Sports Illustrated and wrote the definitive piece on Chaney. Here's how he did it.

This is the story of The Whittler and The Writer. They met in late 1993, and by then, long before he died Friday at age 89, The Whittler already had seen his life chronicled in just about every manner and from every imaginable angle. There had already been one book written about him, and another would follow, and in subsequent years another dozen writers who knew him well and covered him intimately could have written another dozen books about him. Maybe two.

But in the days since The Whittler’s death, on Twitter and Facebook and out of dusty basement boxes where old magazines are stored, people keep coming back to this one piece about him, the definitive piece about him, the piece that captured John Chaney better and revealed more about him than any other before or since.

A man’s born into crazy ...

The test of time

Before this gets more meta than it already is, let’s clean up the clutter first. Here’s what you need to know about The Writer: Native of Wilmington, Del. Alumnus of La Salle University, Class of ’75. Spent a year at the Daily News as a beat writer covering West Philadelphia High School basketball star Gene Banks — not covering high school sports, not covering one sport at one high school, covering one athlete who played one sport at one high school — before tracking Dick Vermeil and the Eagles to Super Bowl XV.

Decided the column inches of a tabloid were too confining. Traveled the globe. Returned to the United States. Wrote for Inside Sports before Sports Illustrated scooped him up in the late 1980s, and in time an entire generation of aspiring sportswriters (ahem) would fall under his spell, mimic his rat-a-tat writing style and repeated rhetorical questions (double-ahem), and aspire to get their subjects to bare their souls to them the way his did to him.

Muhammad Ali. Mike Tyson. Mia Hamm. Magic Johnson. He profiled them all and more. One story … God. One story was about a high school basketball player, a Black teenager who had lived his whole life without an apparent blemish until he was accused of rape, a story with as many sides as a diamond, and The Writer dropped the periodic table right in the middle of the freaking narrative. Go ahead. You find a way to weave a tapestry about sports and race and gender and sex and power and the presumption of innocence and to link all those third rails to … cesium. You find a way to have that story not only make sense but also treat those topics with the gravity and dignity they deserve and demand, to have that story pose fresher, deeper questions, and to have that story read like a dream. Maybe then you’ll win a record four National Magazine Awards. Maybe then you’ll be regarded as the best long-form sportswriter ever. Maybe then you’ll be as good as Gary Smith.

One day, someone at SI suggests a story idea to him: What about the men’s basketball coach at Temple? Three Elite Eight appearances in the last six years. Makes his players practice at 5:30 a.m. Rails against the NCAA and racism in preacher-style monologues hilarious and furious and thought-provoking. Gary, wanna go back to your old stomping grounds?

Hell, yes. And when he does, he produces 7,000 words for the Feb. 28, 1994, issue of SI that stand the test of time, that anyone interested in John Chaney — his friends, his players, perfect strangers — could read and say, Now I know the man, and they wouldn’t need to read anything more.

» READ MORE: John Chaney by the numbers

So at long last, you get to ask the question that you and a million other writers and readers would love to ask him: How the hell did he do it? And with John Chaney, what the hell was it like?

Holding the complexity

The Whittler. That was the story’s headline. The metaphor had come to him immediately, as soon as he arrived at McGonigle Hall and wound his way down into that dark little hole of an office, with its bare-bones simplicity, nothing you would imagine for a coach of such a successful program. And Chaney was sitting there with bags of food on his desk, food that he had already cooked at home to bring in for his players or to hand out to janitors, and bang, they were right into it.

“It was just the accumulation of so many situations and anecdotes where it came down to that,” Smith said the other day in a phone interview. “It just kind of dawned that this is what this guy keeps doing in so many different ways. It’s always reducing the complexity, and obviously you can get simplistic and lose a lot of life, but he held the complexity. He found that, especially for kids coming through the wringer that he’d come through and kids who had come through a similar wringer, the best bet, the surest way for them to knife through all that and get their best selves out to the other side, was through simplifying it.

“It became obvious: ‘This is what the recurring theme is, and let’s play with it.’”

He sat in McGonigle’s stands for Chaney’s pre-dawn practices, stifling giggles as Chaney called his players embryo-heads, told them they should go back to their dorm rooms and make more mucus, screamed at them to stop shooting p---y shots and get back on defense like their asses were on fire. He followed Chaney to the Reading Terminal Market and to his favorite rib joint, watched him shop for vegetables and meats and kibitz with the vendors.

» READ MORE: Inquirer photographers captured John Chaney's life and career

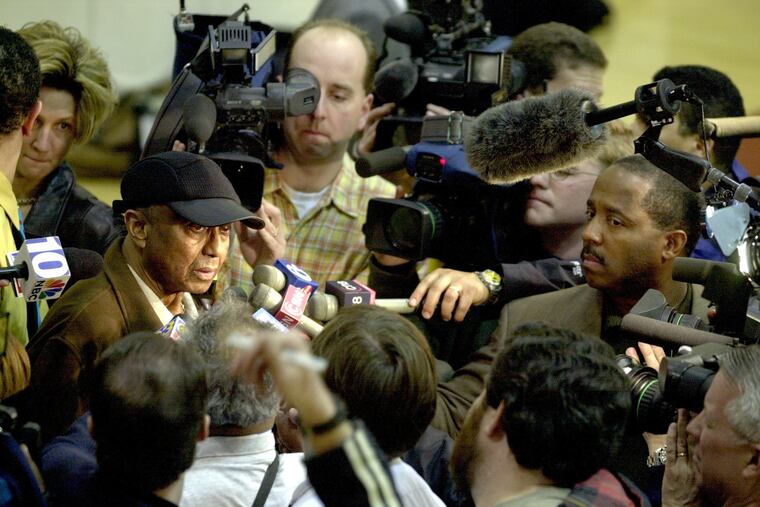

He probed him about his childhood, about an Italian kid in junior-high shop class, Dante, who tormented Chaney until Chaney grabbed a mallet and threatened to bury it in the poor kid’s brain. And a week before the story was published, when Chaney exploded at John Calipari in a postgame press conference, shouting, “I’ll kill you!” and charging after the Massachusetts coach, Smith couldn’t help but see a psychological connection.

“I had a sense that the way he felt with Dante, this Italian kid who bullied him, it came back alive with Calipari being Italian,” Smith said. “I sensed it. That’s why John went over the top. It was like some Italian kid was taking away something rightfully his or his team’s.”

He drove with him to 17th and Ellsworth, where Chaney had grown up, and they parked at the corner and turned the car off and stared at the second-floor apartment “that was so cold in winter,” Smith wrote, “you had to go outside to warm up.” And Chaney, vapor rising from his mouth, would talk to Smith about looking up at those windows and bedrooms and remembering what happened there, about keeping that past and that hurt fresh and alive so he could always understand what his players were dealing with, fearful that if he didn’t keep it close at hand, if he lost contact with it, he couldn’t be the coach and teacher he needed to be. And Smith, a yellow legal pad in his lap, would scribble for all he was worth because now he could write about that past through the lens of the man who was there, who lived it, who was still living it.

You know, when you’re young, it seems like so many things goin’ on in the world. When you’re old, seems like just two things happenin’. Birth and dyin’. My sister, my brother, my stepfather, my mother ... I buried them all in the ’80s. Why am I the last one left? Is it because the worst is waiting for me? Or because I‘m privileged? Am I left here to be special? Or to be tortured? I don’t understand … I’m just gonna disappear someday. I know myself. I’m nothin’ but an exclamation point, and one day I’m just gonna shout it out … Excuse me! ... while I disappear.

The old bull

Now go. Get to Google and find the piece. It’s still snowy out there and cozy in here. Settle in and read. How did he do it? Let the old man say it as only he could. Let The Whittler have the last word.

Smith had returned to his home in Charleston, S.C., and his writing process was always the same: He’d set his stack of bulging legal pads on his desk, and he’d type up his notes, organizing them into chronological or thematic categories, and the typing would spawn more questions, and he’d have to call back his subjects again and again, Chaney more than most. “I wore his ass out,” Smith said, “but that’s how I pretty much did my stories. Maybe a little more with him because I couldn’t wait to call him back. I was gleeful to come up with 10 more questions.”

So he rang him up one more time with another fusillade of follow-ups, another round of fact-confirming and detail-seeking, and Chaney finally stopped him.

“You know that joke about the old bull and the young bull?”

“No, John.”

“Old bull and young bull, looking down at a valley from a hill. A whole herd of young, beautiful cows are down there in the meadow of the valley. Young bull says, ‘Let’s run down there and screw one.’ The old bull says, ‘No, let’s walk down and screw ‘em all.’”

Then John Chaney paused, and Gary Smith waited for the punchline after the punchline, waited for that voice so raspy and worn ...

“Gary, you da old bull.”