Meat crisis undoes lesson of classic 1906 novel | Will Bunch Newsletter

A deadly crisis in meat plants undoes the lessons of Sinclair's The Jungle, plus your ideas on national service.

We made it into May! Welcome back, and if someone forwarded you this email or you somehow stumbled aboard without signing up to get The Will Bunch Newsletter delivered weekly to your inbox, then today’s a great day to do that. It’s easy, at inquirer.com/bunch. And to mark #GivingTuesdayNow, the Lenfest Institute is matching, dollar for dollar, your donation to support the Inquirer’s public journalism—a great cause. Learn more and give here.

Coronavirus shows how America unlearned the moral of Sinclair’s ‘The Jungle’

I read something that seemed particularly apt, given the ongoing global pandemic and the horrific impact it’s been having on America’s meatpacking industry, where thousands – many of them immigrants – have fallen ill to COVID-19 and at least 20 have died:.

“Here was a population, low-class and mostly foreign, hanging always on the verge of starvation, and dependent for its opportunities of life upon the whim of men every bit as brutal and unscrupulous as the old-time slave drivers.”

To be clear, I read that sometime in the mid-1970s, when I was a high school student. And the classic work of literature it comes from – Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle – was published way back in 1906, a bygone era of runaway capitalism creating vast contrasts of wealth and poverty, where a poor, largely immigrant labor force desperate to feed its families was often exploited. (Sounds familiar.)

When we read The Jungle in high school 45 years ago, its backstory reeked of triumph — that great literature can also change the world. Just months after Sinclair’s tome was published, progressive-minded Theodore Roosevelt pushed through the Meat Inspection Act of 1906. But as this excellent analysis points out, Roosevelt’s reforms were aimed at making meat safer to eat for consumers but didn’t protect the workers whose plight was chronicled in The Jungle; that only came decades later, thanks to the labor activism of unions.

Over the last 50 years or so, while kids like me were taught to slap America on the back for our progress, everything changed. Unions declined. Rules once enacted in the spirit of Sinclair and TR disappeared. A new wave of immigrants – not from Eastern Europe as in 1906 but black and brown people from Mexico or Central America or Africa – now arrived willing to take these jobs on the bottom rung.

Most people weren’t looking, though, at America’s meat plants until the last few weeks, as when the spread of the coronavirus through these large facilities where employees typically work in close quarters – and which remained open to keep supplying food to Americans on lockdown –even hit states like South Dakota with few other cases.

We should have been paying attention. In 2005, the non-profit Human Rights Watch issued a highly damning report on workers’ rights and conditions in the nation’s meat processing facilities, including shockingly high rates of injuries – from an array of moving objects, sharp cutting tools and the strain of repetitive motion – and even death.

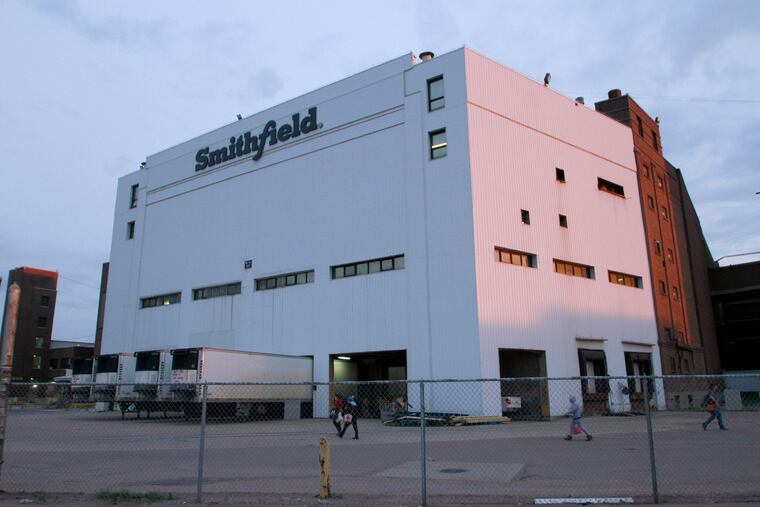

In September 2019 – that would be six months before the first coronavirus death in the United States – HRW revisited the issue and found that the lives of many workers in America’s meatpacking plants are still consumed with managing injuries, illness and chronic pain. “We’ve already gone from the line of exhaustion to the line of pain.… When we’re dead and buried, our bones will keep hurting,” Ignacio Davalos, a worker at a Smithfield-owned hog plant in Crete, Neb., told the human-rights organization.

If you’ve been paying attention these last three-plus years, it won’t shock you to learn that the response from President Trump and his administration to the plight of these workers has been to significantly weaken the rules on their “brutal and unscrupulous” owners. Under Trump, the main agency that regulates worker safety – the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, or OSHA – has conducted fewer inspections than any time in its history. Since the coronavirus arrived, even industry officials have complained about the lack of guidance from OSHA or any other federal agencies about how to keep workers safe.

The current situation is a mess. Despite the large-scale coronavirus outbreaks, Trump – a Meat Lover’s President if there ever was one – has ordered the plants to stay open to salvage America’s food chain. The workers don’t want to die from COVID-19 yet desperately need their paycheck, and many get overtime or even incentive pay for NOT calling in sick. That keeps food on their table but sets the stage for more disease.

It never should have come to this. A government for the people could have – should have – made these plants safer when the economy was good. Upton Sinclair warned us to clear out The Jungle 114 years ago. Shame on all of us for letting it grow back.

Feedback Loop

I was blown away by the response to last week’s call for a mandatory national service. About 30 or more (OK, I lost count) emailed me back with your own ideas, with most (but not all) pretty supportive. I’m printing a few quotes from your emails here:

I joined the US Army upon graduating from Bartram (in 1965) and experienced the blending of young men from all over. The transition for some was not easy whether it was racial, cultural or economic. In the Army, one learns quickly about discipline and teamwork. You learn, not only to depend on each other, but also to extend help to those that have trouble keeping up. – Lou DiScioli

Many of your points on a MNS are worthy. But, even cumulatively, they are superseded by the simple fact that such a policy would amount to involuntary servitude, a clear violation of the 13th Amendment. – Daniel Fleisher

I have often lamented how EVERYTHING is so fragmented now, we don’t have anything in common with each other, not like years ago, not even little popular culture things. – Kristina Hartley

Perhaps the entitled attitude a lot of kids have today would be wiped clean when they see how others live each day in a pure survival mode — Louis Skatz

Additionally, as you point out, it could bring together kids who would otherwise never meet, never travel, never get outside their narrow cocoons. – Flora Wolf

My time on active duty in the Army was something that I cherish. Not because I liked being in the military. I feel that it served as an eye opener about other people’s culture throughout the US and it was a deeply enriching experience. It really does give one the understanding that "we’re all in this together.” – Barry Grossman