Nearly 50 years after panic gripped suburbia, a new book, a key witness, and a confession

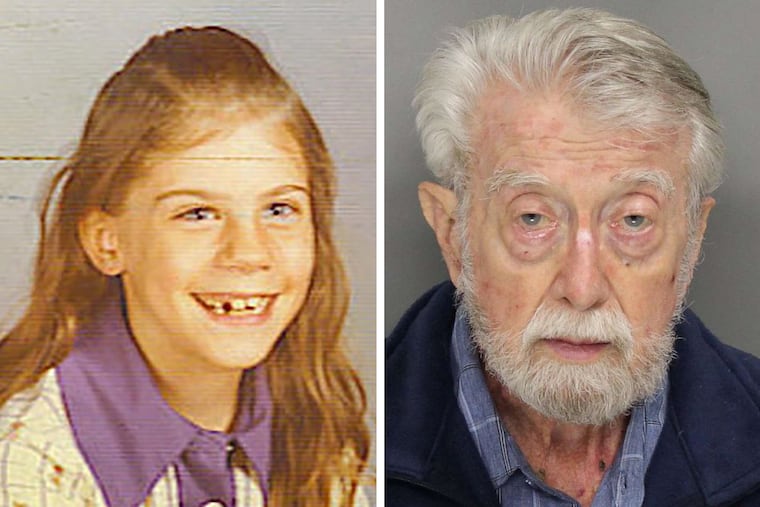

In a Georgia police station this month, David Zandstra cracked when presented with new evidence. Police say the retired reverend confessed to murdering 8-year-old Gretchen Harrington in 1975.

Robert Jordan was playing in his backyard on Aug. 15, 1975, another summer afternoon in his idyllic Delaware County neighborhood, when the panic began to spread from house to house.

Gretchen Harrington, an 8-year-old girl from his Bible camp, was missing.

“I remember being asked, ‘Have you seen Gretchen?’ and saying, ‘No, why?’” Jordan, who was 9 years old at the time, recalled this week.

The Amber Alert system wouldn’t begin for two more decades. There were no cell phones. No Facebook, Citizen or Nextdoor apps.

But through a network of suburban moms, everyone in Jordan’s Marple Township neighborhood seemed to hear the news at nearly the same time.

“It went right down the line, housewives not even getting on the phone, just going to tell each other something had happened,” Jordan said. “We knew something was happening because our mothers were so jittery.”

They sprang into action. Jordan piled into a neighbor’s Volkswagen van with his mother and four other kids. Their search began at a nearby park.

Hundreds of residents from Marple and neighboring towns would later comb wooded areas with no results. Tracking dogs were called in. Even a psychic.

“We haven’t got a thing, not a thing,” then-Broomall Fire Chief Knute Keober told The Inquirer two days after Gretchen’s disappearance. “If she’s in the area, she’s by Jesus well-hidden.”

It wasn’t until Oct. 14, 1975, that a hiker found skeletal remains along a path in Ridley Creek State Park. At first, he thought they belonged to an animal.

“I looked closely and saw what I thought was fingernails,” the man told police, according to a new book on the case. The body was positively identified as that of Gretchen Harrington. It bore signs of blunt force trauma to her skull. Her death was ruled a homicide.

Jordan, 57, now a health care marketing executive, still thinks of Gretchen and that summer each time he drives down Lawrence Road, the last place she was seen.

He remembers the Bible camp. Hot dogs and baked beans. Kickball and Wiffle ball. Then, an abduction and a murder. It haunted families for years.

“So many young people from the ‘70s still bear that pain and anxiety today,” he said. “She was a lovely girl.”

‘It was always a dead end’

Brandon Graeff was 2 years old when Gretchen Harrington’s body was found. The case had long turned cold by 1997, when he joined the Marple Township police force.

Tips had poured in early on, then slowed. Detectives pursued them all, on and off the clock.

“Everything — and I mean everything — was followed up on,” said Graeff, who became chief in 2020.

The case came up from time to time, in roll call, or when a detective would grab the folder again during a slow week.

“They’d look through it, maybe try to see something different for her,” Graeff said, “But we couldn’t. We didn’t. It was always a dead end.”

Since 1975, the case has proceeded along two tracks: the abduction handled by Marple Police, and the homicide by state police, because the park in Edgmont Township is in their jurisdiction.

In early 2021, Graeff got a call from a man named Mike Mathis, who said he and another former township resident, Joanna Sullivan, were working on a book about the murder and were hoping the department would cooperate with granting them some access to the files.

With little movement in the investigation in decades, Graeff couldn’t think of a good reason to say no.

“We’re dealing with a little girl whose killer was not held to account,” he said. “My question to myself was, ‘Why not? How could it hurt?’”

Sullivan, 57, remembers being at Lawrence Park Swim club the day that Gretchen disappeared. The image of a hovering helicopter was seared into her memory.

“We were just at the pool on a hot summer day and the helicopter was overhead,” she said. “We were wondering what was going on. Then we heard.”

Mathis, 58, remembers his father joining the search for Gretchen. He and Sullivan would meet a few years later at Paxon Hollow Middle School. They were editors at the student newspaper, The Hollow Log.

They kept in touch through high school and beyond. At a reunion decades later, they’d talk about writing a book together about Gretchen.

“It just stayed with me and Mike and many other kids through the years,” said Sullivan, now the editor-in-chief of the Baltimore Business Journal. “I always thought I’d like to write that story.”

When COVID struck in 2020, Sullivan and Mathis suddenly had more time. They got started by creating a list of people they wanted to interview.

“At the top of the list,” she said, “was the Zandstra family.”

The book, Marple’s Gretchen Harrington Tragedy: Kidnapping, Murder and Innocence Lost in Suburban Philadelphia, was published in October 2022. Sullivan and Mathis did a round of public appearances in the area, including a December book signing at the Barnes & Noble in the Lawrence Park Shopping Center — just down the street from where Gretchen was abducted.

They had no idea that, just a few weeks later, a woman would come forward with information that would break the case wide open.

“I think it was Mr. Z”

On Jan. 2, 2023, state police interviewed a woman later identified in court documents only by her initials. She said she’d frequently slept at the home of a local reverend named David Zandstra and his family because she was friends with his daughter.

Zandstra had served at Trinity Chapel Christian Reformed Church, one of two churches on Lawrence Road in Marple Township that were used for the Bible camp that Gretchen attended. The other was the Reformed Presbyterian Church, where Gretchen’s father was the pastor.

It was Zandstra who called police and reported Gretchen missing at 11:23 a.m. on Aug. 15, 1975. He said he was calling at the request of the girl’s father.

The new witness told state investigators that during two sleepovers at the Zandstra house when she was 10 years old, she awoke to Zandstra touching her. She also showed police a childhood diary she’d kept that mentioned the sleepovers and, in September 1975, her suspicion that Zandstra might have been involved with the attempted kidnapping of a girl in her class, as well as Gretchen’s disappearance.

“It’s a secret, so I can’t tell anyone, but I think he might be the one who kidnapped Gretchen,” she wrote. “I think it was Mr. Z.”

At first, a cordial interview

Earlier this month, David Zandstra, 83 and living in Marietta, Ga., walked into an interview room at the Cobb County Police Headquarters with no reservations about speaking with police. He didn’t lawyer up. It was the department’s “soft” interview room. Couch, comfortable chairs, unlocked.

Two Pennsylvania troopers were waiting for him: Cpl. Andrew Martin, who had picked up the Harrington case about 2017, and Eugene Tray, who’d been called in recently. They’d caught a flight to Atlanta on July 17 to interview the octogenarian suspect, with the new information in hand.

If Zandstra was worried about the interview when he sat down, he didn’t show it — at least not at first.

Back in 1975, police had interviewed Zandstra twice. He also spoke to Mathis for the book, which focused on a different man as the prime suspect.

“Deep down, I’m sure he was very, very concerned,” Tray said.

The conversation was almost cordial to start. Zandstra denied ever seeing Gretchen on the day she went missing.

But then police told Zandstra about the sexual assault allegations from the girl with the diary. It was the final straw placed on top of nearly a half-century of guilt. He broke down and confessed.

“We asked and he spoke,” Tray said. “He was presented with things I don’t think he expected to be presented with. Then, I think he started to think more on it. I think he just wanted his sick, twisted version of redemption, and to come clean.”

Zandstra admitted to abducting Gretchen as she was walking to Trinity Chapel for morning exercises, according to the criminal complaint. He said Gretchen asked to go home, but he drove her to a wooded area and parked. When she refused his demand to take off her clothes, he struck her in the head with his fist, court documents state.

Zandstra said he checked her pulse and believed that she had died, so he attempted to cover up her half-naked body with sticks and left the area.

“He was two different people,” Tray said of Zandstra, before and after his confession. “He was definitely relieved and happy to get that off his chest, how sick that may be.”

Searching for other victims

Zandstra left Delaware County in 1976, and worked in Texas and California before retiring to Georgia. Cops in and around Marple Township who’d worked on the case, or helped search for Gretchen in 1975, have retired and died.

The case took a toll on many of them, knowing a child killer could have gotten away with it, said Delaware County District Attorney Jack Stollsteimer, who was 12 years old when Gretchen disappeared.

“It’s important to understand law enforcement officers are moved by the trauma they see happen,” he said. “That’s why they’re in this business of trying to bring justice.”

Stollsteimer described Zandstra’s arrest as a “great relief” to police in Delaware County and praised Martin, in particular, for sticking with the case.

“This is just great, old-fashioned police work,” he said.

Martin was unable to attend the news conference on Monday announcing Zandstra’s arrest and was not available for an interview this week. Tray, however, said the “case would not have been solved were it not for him.”

State police collected DNA from Zandstra when he was arrested, which could prove useful if there are additional victims in other parts of the country.

As part of that effort, the Christian Reformed Church in North America says it is reaching out to Zandstra’s former congregations. He served in Flanders, N.J.; Broomall, Pa.; Plano, Texas; and San Diego and Fairfield, Calif.

After settling in Georgia, Zandstra continued to advise clients of a pregnancy resource center, according to a 2012 religious newsletter in which he wrote a small section titled “Peace to you.” A photo shows him smiling, with gray hair and a closely cropped beard.

“The prospect of peace was and is badly needed in the uncounted and constant conflicts of our world,” he wrote. “Only believers in Jesus are able to find real peace with God.”

California police are now looking into whether Zandstra might be connected to the 1991 disappearance of 4-year-old Nikki Campbell in Fairfield, and police in Delaware County are also reexamining other cases from the 1970s.

“Who knows? This guy was a monster,” Stollsteimer said. “Nothing would surprise me.”

Sullivan, the author of the book on the Harrington murder, has been fielding calls and Facebook messages this week from people in Marple who might have information about other cases of abuse.

“I don’t think it was an isolated case,” Sullivan said.

As for whether the book helped lead to the break in the case, that depends on whom you ask. Some law enforcement officials are convinced that it did. Others cautioned against such speculation. Regardless, a new chapter is planned if the book goes to another printing: Case solved.

On Friday, the Delco DA’s office got word that Zandstra would waive an extradition hearing and agree to be transported from Georgia to Pennsylvania. But his defense lawyer later sought to have the waiver recalled because he was not present with Zandstra when it was signed. Authorities are awaiting a judge’s ruling.

The Harrington family released a statement this week, thanking police for their work and community members for their support over the years. Gretchen’s father, Harold, died in November 2021 at the age of 94.

“If you met Gretchen, you were instantly her friend,” the family wrote. ”She exuded kindness to all and was sweet and gentle. Even now, when people share their memories of her, the first thing they talk about is how amazing she was and still is. At just 8 years old, she had a lifelong impact on those around her.”