Rare, risky, and complex, lung transplants for COVID-19 survivors save, but change, lives

Only about 100 have been performed on these patients in the U.S., with Temple University Hospital and the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania together performing almost 20 of them.

For a few COVID-19 survivors, people with lungs so scarred they can barely draw a breath, a lung transplant is the last hope.

The surgery, “medically the most complex procedure that can be done,” said Ankit Bharat, a Chicago-area transplant surgeon who pioneered its use to save COVID-19 patients, is available only to a few.

“To be a transplant candidate you’ve got to be sick enough to need a lung transplant as well as well enough to undergo the procedure,” said Sameep Sehgal, a pulmonologist at Temple University Hospital. “It’s a very small group.”

Only about 100 have been performed on COVID-19 patients in the U.S., with Temple and the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania together performing almost 20 of them. All but one of the hospitals’ patients who underwent the procedure have survived.

» READ MORE: It’s a boy! Philly-area couple and Penn Medicine celebrate first birth from uterine transplant program.

People lucky enough to get new lungs face a significantly altered life and the permanent possibility that the transplanted organs could be rejected or fail. But the procedure also offers a future that can again be measured in years, instead of weeks.

“I love a cold beer. Can’t have it. Last time I had a beer was Super Bowl Sunday,” said Jack Silknitter, a 68-year-old who received a single lung transplant in April at Temple. “I’d rather live than have that.”

‘Very, very difficult’

Initially, hospitals hesitated to offer lung transplants to COVID-19 patients, thinking they would not be good transplant candidates, said Bharat, chief of thoracic surgery and surgical director of the Northwestern Medicine Lung Transplant Program, the first in the U.S. to do a post-COVID-19 lung transplant in 2020. It wasn’t clear if they had the strength to recover, if the new lungs would be infected with the virus, or if doctors might be exposed to dangerous levels of the coronavirus by operating on the lungs.

A key discovery, he said, was that a few weeks after infection the COVID-19 virus leaves patients’ bodies, and so cannot infect new lungs or endanger surgeons.

Plus, these patients’ bodies are often healthier than those of more typical transplant candidates, who have been wearied by years of smoking, or a disease like cystic fibrosis. Some only in their 20s or 30s had been well until contracting the virus, potentially leaving them better able to recover.

“Just because it’s not been done,” said Bharat, “we didn’t have any evidence to say it cannot be done.”

That ambitious statement echoes comments from Philadelphia-area thoracic specialists drawn to the field by the challenge of solving previously unanswered medical questions and difficult complications.

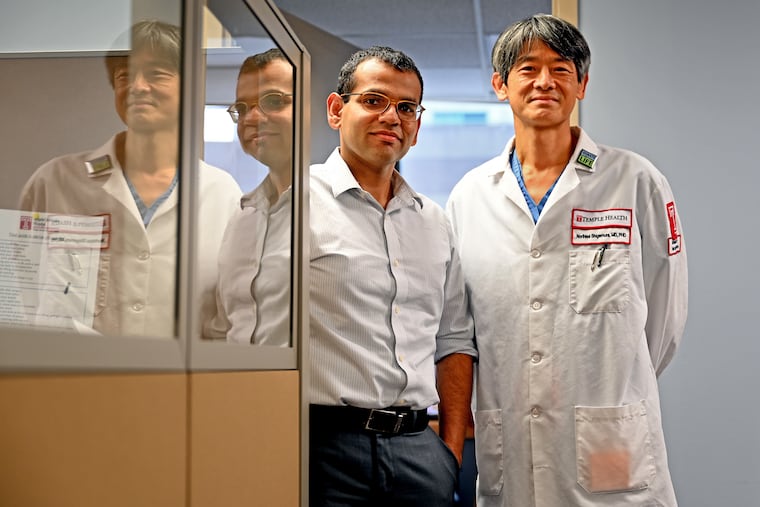

“It’s complex and complicated and there are many things remaining to be cleared, to be answered, from specialists’ standpoints,” said Norihisa Shigemura, a Temple physician who performs lung transplants. “That has driven me to stay on this specialty and stay on this position to take care of such challenging patients.”

To successfully complete a lung transplant, doctors must master a trifecta of critical connections. In a procedure that can last five to eight hours, they attach the new lung to airways, reconnect the artery that brings blood to the lungs, and attach the vein that takes blood back to the heart, some of which must be performed by reaching behind the beating heart to complete the surgery.

“Those attachments are very, very difficult and prone to complications,” Bharat said. “One error could lead to catastrophic complications.”

With its many ways of damaging the human body, COVID-19 only multiplied the difficulty.

“They have bleeding,” Christian Bermudez, director of thoracic medicine at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, said of lungs damaged by COVID-19, “they have lung complications, chest complications.”

Cost of living

Penn and Temple waited until this year to do COVID-19 lung transplants to be certain, doctors said, that they had enough information to give lungs to patients most likely to recover. The selection process for all transplants includes doctors, pharmacists, physical therapists, and social workers looking at factors like age, body mass index, and the patient’s overall strength. COVID-19 added another dimension of complexity.

“The stakes are really high, were really high, and are still really high,” Bermudez said.

Patients on ventilators are often not eligible, Bermudez said, because their condition deteriorates due to damage the ventilator can cause to lung tissue or infections it can introduce. Many people eligible for transplants are on an extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) machine, which adds oxygen to blood when lungs can’t and often allows patients to remain conscious and able to move. ECMO is a short-term solution, though. Because of infection and inflammation risks, patients typically live no more than four and a half months while relying on the machines.

Silknitter recalled his life in the weeks before his transplant, when his damaged lungs were operating at a third their normal capacity.

“To roll over in bed, just to roll over, I was out of oxygen,” he said. “You think you’re going to get better and you don’t.”

He was home for about a week before his transplant, relying on oxygen tanks to keep him alive. His family had placed chairs around the house so he could sit down after walking a few steps. The experience of trying to catch a breath could be terrifying.

“You’re breathing,” he said, “but it’s not doing anything.”

His wife, Pat, feared a new organ wouldn’t come in time.

“The week before he got the transplant I pretty much thought if he didn’t get it quite soon it would be the end,” she said.

This year, more than 2,800 people nationally have died while waiting for a lung transplant, according to Gift of Life, the Philadelphia organization that connects donor organs with patients. Scarcity is endemic in the world of transplants, and delicate lungs are especially challenging, said its vice president of clinical services, Rick Hasz. Just 1% to 2% of all deaths in the United States happen under conditions that make internal organ transplants possible, and of those, just a quarter provide viable lungs.

“We’re in a supply and demand deficit all the time,” Hasz said.

There are 993 people currently waiting for donor lungs in the United States, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network.

Bermudez said at least three of his COVID-19 patients died while waiting for donor organs. One reason doctors are reluctant to give transplants to people on ventilators is that they can’t participate in deciding whether they want the surgery, Bermudez said.

Silknitter was on the waiting list for just a week before he got the call about 11 p.m. to be at Temple Hospital for a 5 a.m. transplant.

By then, he was well aware that new lungs came with many strings attached.

» READ MORE: Some COVID-19 long haulers have had symptoms since the first wave. Can they still get better?

As with other transplants, patients face a lifetime regimen of powerful immunosuppressant drugs that affect the immune system, requiring patients to take extra precautions to stay healthy. Transplanted lungs are constantly exposed to the outside environment and all the bacteria and fungi that could be present in every breath of air.

Protecting his new lung, Silknitter learned, requires giving up alcohol and meat that isn’t well done, and thoroughly cleaning raw fruits and vegetables.

A schedule of frequent doctor visits and tests for life is another reality, yet they can’t offer complete protection from a first year of recovery that is rarely problem free, or from an ongoing risk of organ rejection.

And there are unexpected complications. Just this weekend, an outpatient lung biopsy turned into an overnight hospital stay when Silknitter had a delayed negative reaction to an anesthetic drug.

COVID-19 survivors seeking transplants face these radical choices after going from healthy to mortally ill in a matter of weeks.

“To go from having no medical problems three months back …,” Sehgal said. “It can have a significant psychological impact on the patients.”

The warnings, however, haven’t discouraged anyone who has been offered a chance at life.

“All of them wanted it,” Bermudez said.

‘It’s special’

After his surgery, Silknitter was unconscious for days, and then his moments of awareness were haunted by hallucinations — not an uncommon phenomenon among long-term ICU patients. For nine days, he could consume no water or food.

“That was probably the worst part,” he said. “No liquid. It’s like a desert.”

But less than a week after the operation, he took his first steps. Just over two weeks post-op, he transferred to a rehab facility. Less than a month after receiving his transplant, he went home.

Up to 60% of lung transplant patients survive five years, Shigemura said, but those statistics are based on pre-COVID-19 patterns. The younger, healthier people receiving organs after coronavirus infections may stretch estimates of how long transplanted lungs can extend a life.

Though COVID-19 hospitalizations in Philadelphia are far below where they were just months ago, both Temple and Penn have patients currently waiting for donor organs. Treating them has left physicians little time to think about how close their transplant patients came to death.

“Frankly, I haven’t had such good time to reflect or think about it,” Shigemura said. “In reality, after one issue was resolved the other issues, questions, keep coming.”

About two months after Silknitter’s surgery, breathing is easy.

Recovery has mostly meant rebuilding his endurance after months of barely moving. He can walk about a quarter of a mile without a cane, and has been leaving the house for brief excursions.

When he had his surgery, Silknitter set a goal to attend a charity golf event established in memory of his brother, Ron, who died 15 years ago. A week and a half after leaving the hospital, Silknitter was at Gilbertsville Golf Course. He couldn’t get around well or stay long. He certainly couldn’t play golf. But he was there.

“With me being as sick as I was,” he said, his voice shaking with emotion, “and the friends I have there, it’s special.”

To learn more about organ donation, or to register to be a donor, go to Gift of Life’s web site at donors1.org