Two friends shared heroin in a KFC bathroom. One died, one went to prison. Their families are picking up the pieces.

The prosecution of Emma Semler for her role in Jenny Werstler’s 2014 fatal overdose demonstrates that in the opioid crisis, the line between death and life, victim and perpetrator, can be thin.

Last week, Margaret and Ted Werstler sat on their back porch in West Chester, watching a thunderstorm roll in and trying to reconcile the questions that lingered over the death of their only child.

On the May 2014 night that she turned 20, Jenny Werstler overdosed on the floor of a KFC bathroom in a West Philadelphia neighborhood, miles from her suburban home. The two friends who had used heroin with her there — 19-year-old Emma Semler and her 17-year-old sister, Sarah — panicked and left her.

Five years later, a federal judge sentenced Emma to 21 years in prison for supplying the drugs that killed the Werstlers’ daughter.

But there is more blame to go around, Ted Werstler said as the clouds thickened. The pharmaceutical companies that flooded communities like his with opioid pain pills, which Jenny first tried as a teenager. A system that forced their daughter to come back from a Florida halfway house for a court date before she was solid in her recovery. She died one day after that court appearance.

The Werstlers said they don’t believe Emma Semler intended for their daughter to overdose. But thinking of Jenny’s last moments was unbearable.

Emma “didn’t want Jenny to die. But how could you leave another person in that bathroom?” her father said.

More than 4,500 other people have lost their lives to heroin overdoses in Philadelphia since Jenny Werstler. Behind them all are tales of destroyed families, rippling grief, and confounding questions.

The case that began with Jenny’s death and ended with Emma’s sentencing offers a window into how the addiction crisis topples lives, rips families apart, and leads frustrated law enforcement officials to reach for drastic measures they hope — but cannot be certain — will prevent more deaths. Federal prosecutors charged Semler under a law designed to go after drug dealers but one that prosecutors have used increasingly to target users, like Emma, with stiff two-decade mandatory minimum sentences.

Pieced together through interviews and hundreds of pages of court records and transcripts, the story of Jenny and Emma demonstrates that in the opioid crisis, the line between death and life, victim and perpetrator, can be thin.

“This was a sad and tragic loss of life,” one of Semler’s lawyers, Lynanne Wescott, said at the trial. “But is every tragedy a crime?”

Asking for an extra hit

The three young women who entered the KFC on 61st Street and Lancaster Avenue made a beeline to the bathroom with one shared goal — their next high.

Inside, Emma passed the packets of heroin she had just bought from a drug dealer to Sarah and Jenny, and handed them needles.

Just home from Florida, Jenny asked for an extra hit. It was her birthday.

Minutes later, Jenny’s head dipped low and her breathing slowed. The Semler sisters recognized the signs; both had overdosed in the past.

They splashed Jenny’s face with water, but she didn’t respond. Terrified, the young women packed up their remaining drugs and left.

Moments later, an employee found the young woman on the floor and called an ambulance. Within 30 minutes, Jenny was dead.

‘I tried to open her eyes’

Just having Jenny back home from Florida had Ted and Margaret Werstler on edge. For more than a year, they had endured the crushing cycle familiar to so many parents of addicted teens: Rehab, relapse, then repeat.

Margaret Werstler, a native of Gdansk, Poland, struggled to understand how her daughter — the once-bubbly girl she called her “Polish Princess” — had fallen into addiction.

At age 7, the vivacious, thrill-seeking girl flew on her own to visit her maternal grandparents in Eastern Europe. By her teen years, she was fluent in English and Polish and spoke of one day opening her own business, like her father.

But her addiction, which her parents discovered when she was around 14, became her singular focus.

At first, her parents believed Jenny was only smoking pot. In 2013, a psychiatrist told Margaret Werstler her daughter had admitted to using heroin.

During her second rehab stint later that year at the Malvern Institute in Delaware County, Jenny met Emma Semler.

Growing up in Montgomery County as the daughter of two Merck employees, Emma had been a high school cheerleader. She loved art and music and talked about becoming a nurse.

Her parents’ contentious divorce roiled her family. She began smoking pot at 12, encouraged, she would later tell court officials, by her father, who gave his daughters alcohol and marijuana along with advice to “experience everything in life at least once.”

At 13 she was prescribed pain pills after a back surgery. The next year, she moved on to crack cocaine, and, by 15, heroin. She was using 10 to 12 bags a day by the time she met Jenny.

By the spring of 2014, Jenny’s parents sent her to Florida, hoping to remove her from her circle of drug-using friends.

It seemed to work for two months — until Jenny had to return home for a May 8 hearing in a marijuana possession case in Chester County drug court. Her parents begged for a postponement, to no avail.

“I was furious,” Margaret Werstler would later recall. “I was afraid of Jenny coming back for the court. I was afraid that something would trigger her, being back in the neighborhood.”

Still, when the call came from Lankenau Medical Center around 9:30 p.m. on May 9, her first thought was that Jenny had been in a car accident.

“I thought, I’m going to go to the hospital, pick her up, and bring her home,” she recalled.

At Lankenau, the doctors broke the news: Jenny had died of an overdose. Her mother passed out. When she woke, officials took her to identify the body.

“I tried to open her eyes; they were closed," Werstler recalled. “I was opening and opening. … I couldn’t believe. How could this be my only child, who is dead?”

A search for answers

Within a day Emma learned her friend was dead. She immediately injected heroin from the same batch that killed Jenny.

Meanwhile, the Werstlers started looking for answers.

They drove to the Overbrook KFC, hoping to piece together their daughter’s last hours, and spoke to the fast-food worker who found Jenny on the bathroom floor. They learned that the ambulance that arrived to treat her had no Narcan, the lifesaving overdose reversal drug that had not yet become as widely available as it is today.

With help from a friend of her daughter’s, Margaret Werstler obsessively pored through Jenny’s phone and Facebook page. She found messages Emma and Jenny had traded just hours before her daughter’s death.

Jenny was short on cash and had asked Emma to front her $10 for a bag of heroin. Emma replied that she would and that she knew a dealer where they could score.

Convinced the messages were evidence of a crime, the Werstlers turned them over to Collegeville police and Chester County detectives.

Weeks passed. Spiraling in grief and rage, Jenny’s mom kept compulsively checking her daughter’s final text messages and Facebook conversations.

She sent scathing messages to Emma through Jenny’s Facebook account. Sometimes, she called Emma’s cell phone from her daughter’s phone, only to sit in silence, listening to Emma’s voice on the recorded message.

“I was torturing myself,” Margaret recalled. “Emma is alive, she is breathing the air, seeing the sun and moon, and my daughter is dead.”

Nearly a year after Jenny’s death, federal agents showed up at the Werstlers’ door.

A ‘strong hammer’

For years, the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration had been investigating a West Philadelphia group that controlled much of the heroin and crack flowing through Overbrook.

With Jenny’s death, agents saw an opportunity — both to provide justice to the Werstlers and to recruit Emma to help them dismantle the traffickers’ operations.

They began building a case against the teen, using a federal statute passed at the height of the 1980s crack-cocaine epidemic. It dictated a 20-year mandatory minimum sentence for drug distribution cases involving a death or serious injury.

Emma may not have been a drug-corner slinger, but prosecutors reasoned that by fronting Jenny the money, making the buy and passing out the heroin, Emma was just as responsible for her death.

Courts had upheld similar arguments before. Though the statute initially was used to target large-scale traffickers or kingpins, the legal definition of a “drug distributor” has been more broadly applied in the three decades since, used to charge drug users who share narcotics or buy a small amount for friends.

The expansion has raised concern among public health advocates, who worry the stiff mandatory punishments in the federal law — and 20 similar state laws — are pushing users into riskier behaviors, such as using drugs alone or running away when a friend overdoses.

“It cuts at cross-purposes with public health interventions,” said Leo Beletsky, an associate professor of law and health science at Northeastern University in Boston. “What is going to be accomplished by spending [money] prosecuting these people, and spending [more] to keep them in federal prison for decades?”

Prosecutors maintain they need the option as a tool to stem opioid-related deaths in their communities.

In Pennsylvania courts, the number of cases ballooned from fewer than 15 in 2013 to more than 200 in 2017, the last year for which statistics were available. At the federal level, Pennsylvania’s three U.S. Attorney’s Offices have also reported a rise — with prosecutors in Pittsburgh alone pursuing 48 such cases in the last six years.

“There’s really no difference between shooting a person with a gun and giving them heroin and killing them,” David Hickton, that city’s ex-U.S. attorney and former cochairman of the White House’s National Heroin Task Force, said in an interview last year.

[Can’t see the chart above? Click here to view the complete article.]

William M. McSwain, the top federal prosecutor in Philadelphia, also praised the law as a “strong hammer” to encourage cooperation in cases like Emma Semler’s. One way a defendant can avoid the 20-year minimum sentence is to deliver agents “substantial assistance” in an ongoing investigation.

Prosecutors offered Sarah Semler an even better deal — immunity in exchange for testifying against her sister. She accepted, though the decision wracked her with guilt, family members said.

Hours before she was to appear before a grand jury hearing evidence in the case, Sarah overdosed on heroin and was revived. Prosecutors put her on the stand anyway, over the objections of her lawyer.

Emma, too, was offered multiple chances to plead guilty and help agents build a case against others. She chose to take her chances in court.

A hard road to recovery

By the time her trial began in December, Emma Semler was far from the girl who passed out heroin packets in that KFC restroom.

Drug-free for three years, the 23-year-old had landed a job at a New Jersey rehab clinic, became active in Narcotics Anonymous, and at one point was sponsoring 10 people in recovery.

It had been a hard road, and like Jenny’s recovery attempts before her death, it had come in fits and starts.

When she finally stopped using in 2015, Emma had been through at least half a dozen stints in rehab, numerous relapses, and several overdoses.

“She was tired of feeling the way she did,” said her aunt, Susan Layton. “And tired of losing friends to drugs.”

Still, no matter how much she had changed, her actions on that 2014 night were damning as prosecutors laid them out in court, especially the decision to leave Jenny behind on the bathroom floor.

Asked to explain that choice to jurors, Sarah testified that their mother had just bailed her and her sister out of jail that morning after they were caught buying drugs in Kensington. They worried what would happen if they were arrested again.

“I was scared. Young. High," Sarah said. "We left.”

A path of darkness

Emma faced a similar question about her decisions at her sentencing last week. Her face streaked with tears, she pleaded with the judge to understand that her choices that night were driven by addiction.

“The disease turns us into people we never thought we would be. It leads us down a path of darkness,” she said. “If I could go back and change anything, I would.”

The next day, she emailed her aunt from prison: “I’m totally numb.”

“She often would say, ‘Why wasn’t it me and not [Jenny]?’ ” Susan Layton said. “Emma was present that day. But we all lost something. Emma lost, and Jenny lost.”

At least five other drug-induced homicide cases, many tied to the same larger investigation in West Philadelphia, are moving their way through the federal courts.

Three others have reached sentencing in the last six years — all involving pill-peddling doctors responsible for feeding addictions of dozens of patients. One of those defendants got a slightly lighter sentence than Emma: the mandatory minimum of 20 years.

“Emma Semler brought this on herself with some strong conduct,” McSwain, the U.S. attorney, said in March. “We did everything we could to get her to plead guilty, and she rolled the dice. When you roll the dice against the federal government, you almost always lose.”

Margaret and Ted Werstler said Emma’s sentence was harsh but not as harsh as their grief.

The framed portrait they had taken to the courtroom for her sentencing is back in its place of honor in the living room. And they have kept Jenny’s bedroom exactly as it was on the day she died. The clothing she wore to the KFC that night, ripped by the medics who tried to save her life, hangs on the closet door.

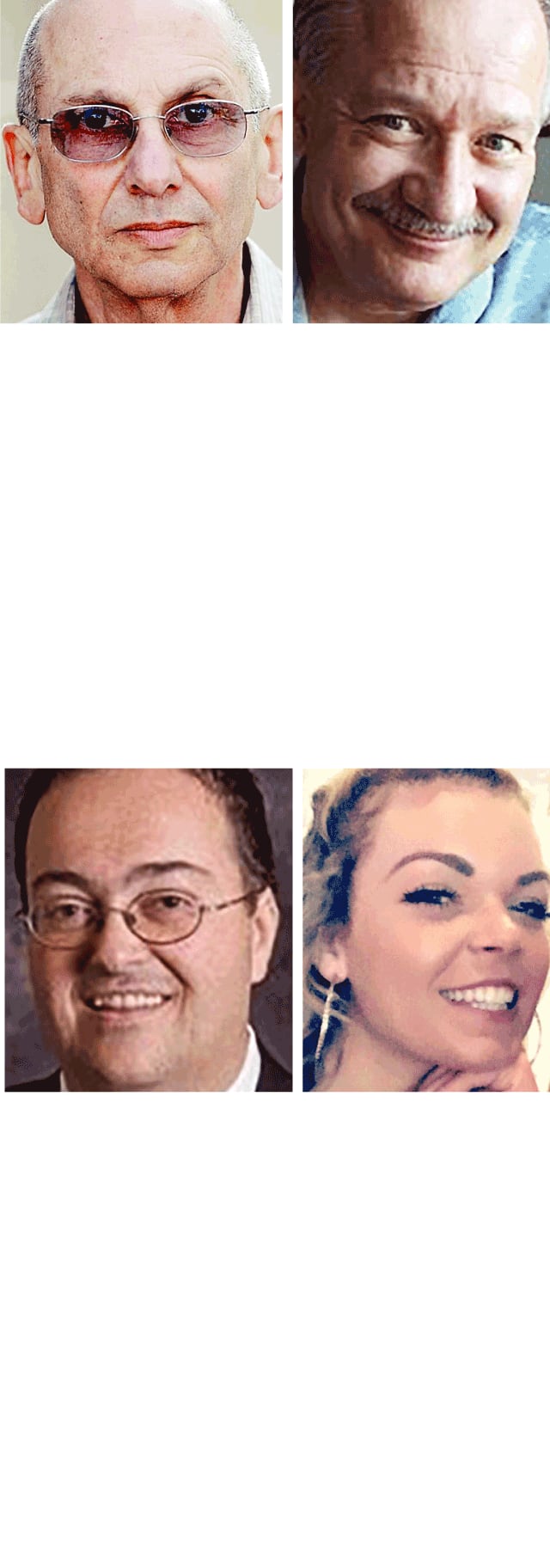

Four Cases Under Federal Drug-Induced Homicide Laws

Since 2011, four defendants in Philadelphia have been sentenced in federal court for overdose death convictions. Each faced a mandatory minimum of 20 years.

NORMAN WERTHER

Sentence: 20 years

Werther, a doctor in Willow Grove, was convicted in 2013 of more than 300 felony counts centered around his overprescribing pain medication to dozens of patients. His reputation for giving away drugs in exchange for a $150 patient visit fee prompted street level drug dealers to organize visits to his office for addicted drug users. One of those patients died.

JEFFREY BADO

Sentence: 25 years

Bado, a former physician, was convicted in 2016 of 308 felony counts, including 269 counts of drug distribution, 33 counts of health care fraud, two counts of lying to federal agents and one count of drug distribution involving death for running his Roxborough and Bryn Mawr offices like a pill mill.

WILLIAM J. O’BRIEN

Sentence: 30 years

O’Brien, convicted of 135 felony counts in 2016, turned his pain-management practice in Bucks County into a drug market and let drug dealers with the Pagans motorcycle gang have full run of his office while trading prescriptions for oral sex. In all, a jury concluded he raked in more than $5 million over three years, feeding addictions for dozens of patients, one of whom died.

EMMA SEMLER

Sentence: 21 years

Convicted in 2017 of two felony counts surrounding the 2014 death of her friend Jenny Werstler. Werstler overdosed as the two women were sharing heroin in a KFC bathroom in Overbrook. Semler and her sister left her there without calling police.

NORMAN WERTHER

Sentence: 20 years

Werther, a doctor in Willow Grove, was convicted in 2013 of more than 300 felony counts centered on his overprescribing pain medication to dozens of patients. His reputation for giving away drugs in exchange for a $150 patient visit fee prompted street-level drug dealers to organize visits to his office for addicted drug users. One of those patients died.

JEFFREY BADO

Sentence: 25 years

Bado, a former physician, was convicted in 2016 of 308 felony counts, including 269 counts of drug distribution, 33 counts of health-care fraud, two counts of lying to federal agents, and one count of drug distribution involving death for running his Roxborough and Bryn Mawr offices like a pill mill.

WILLIAM J. O’BRIEN

Sentence: 30 years

O’Brien, convicted of 135 felony counts in 2016, turned his pain-management practice in Bucks County into a drug market and let drug dealers with the Pagans motorcycle gang have full run of his office while trading prescriptions for oral sex. In all, a jury concluded he raked in more than $5 million over three years, feeding addictions for dozens of patients, one of whom died.

EMMA SEMLER

Sentence: 21 years

Convicted last year of two felony counts surrounding the 2014 death of her friend Jenny Werstler. Werstler overdosed as the two women were sharing heroin in a KFC bathroom in Overbrook. Semler and her sister left her there without calling police.