Philly part of national effort to cut new HIV infections by 90% over 10 years

The CDC has determined that most of the country’s new HIV cases are concentrated in just a few cities and counties, including Philadelphia.

Philadelphia will be one of nearly 50 U.S. cities set to receive special funding and support from the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention aimed at decreasing new HIV infections by 90% in the next 10 years.

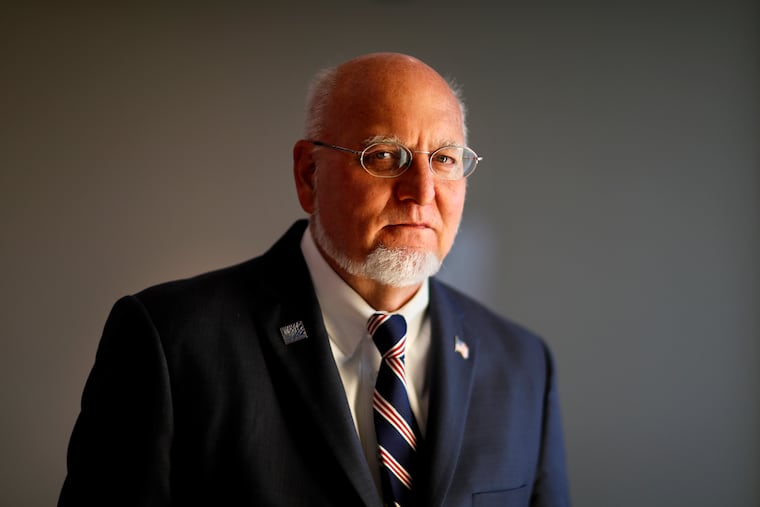

CDC Director Robert R. Redfield said Monday during a visit to Philadelphia that the number of new HIV cases has been dropping steadily since the height of the AIDS epidemic in the early 1990s, when more than 100,000 people a year were newly diagnosed with the virus that can lead to AIDS. But beginning in about 2008, when about 40,000 people a year were diagnosed with HIV, improvement largely stalled, he said.

“It just stagnated there for a decade,” he said. “And it wasn’t because we didn’t have the scientific tools. It’s because we weren’t effective in implementing those tools" — like access to HIV treatment, HIV-prevention drugs, and expanded syringe exchanges, which are proved to prevent HIV among injection drug users.

HIV is spread via blood and other body fluids. It attacks the immune system, and if left unchecked can lead to the late-stage condition, AIDS. Medication therapies enable people to live with HIV for decades but must be taken for life.

The disease could be eradicated, Redfield said, largely because the CDC has determined that most of the country’s new cases are concentrated in just a few places, including Philadelphia. A new push by the agency to decrease HIV infections will target those jurisdictions specifically with funding, staff, and other support.

“We decided to look very carefully at where the new diagnoses were occurring. We went ahead and mapped them, and I think it shocked a lot of leadership, when we saw that those 40,000 new infections, they actually occurred in only 48 jurisdictions,” Redfield said during an interview at the Philadelphia Department of Public Health, where he was meeting with director Thomas Farley and Pennsylvania Surgeon General Rachel Levine. “This is a pretty geographically concentrated situation. Maybe that idea of bringing an end to the HIV epidemic in America is not aspirational.”

Philadelphia has already been awarded $381,444 in planning funds as part of the initiative. The city and other jurisdictions will develop a formal grant proposal for the CDC and apply for more funding to be announced in March.

New HIV diagnoses have been declining steadily in Philadelphia for several years, according to new data from the city health department, including a 14.3% drop between 2017 and 2018. Still, of Pennsylvania’s new HIV infections in the last year, half were reported in Philadelphia.

And the extent of the city’s opioid crisis means that diagnoses have been rising recently among people who inject drugs. Until just a few years ago, officials note, HIV infections had been decreasing in that population since 1992, when the city’s only syringe exchange opened. Today, more people are injecting drugs, and the powerful synthetic opioid fentanyl means users are injecting more often. That’s because the drug, which officials say is contaminating virtually all of the city’s heroin supply, sends drug users into withdrawal faster. More frequent injections to stave off pain means needle sharing — and the risk of HIV — is more likely.

Redfield and Levine said on Monday that syringe exchanges are key to stopping the spread of HIV. A study released last week in the Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome found that Philadelphia’s needle exchange prevented an estimated 10,592 HIV diagnoses in its first 10 years of operation.

“Safe syringe programs benefit the public health of this nation,” Redfield said.

Levine said that she and Gov. Tom Wolf are pushing for legislation to reverse the state’s decades-long ban on syringe exchanges. (Needle exchanges still operate in several Pennsylvania cities with the approval of local officials.) She added that the state’s efforts to treat and prevent HIV also need to focus on African American and LGBTQ patients, who are still disproportionately affected by the disease.

Neither Levine nor Redfield said they supported supervised injection sites, which would allow people to use drugs under medical supervision with clean needles, be revived if they overdose, and access treatment.

Philadelphia officials, including Farley, have said they will sanction a site, and a federal judge recently declared that a nonprofit’s plan to open one did not violate federal law. Still, Levine said, the state would stick to “traditional” harm reduction programs like syringe exchanges.