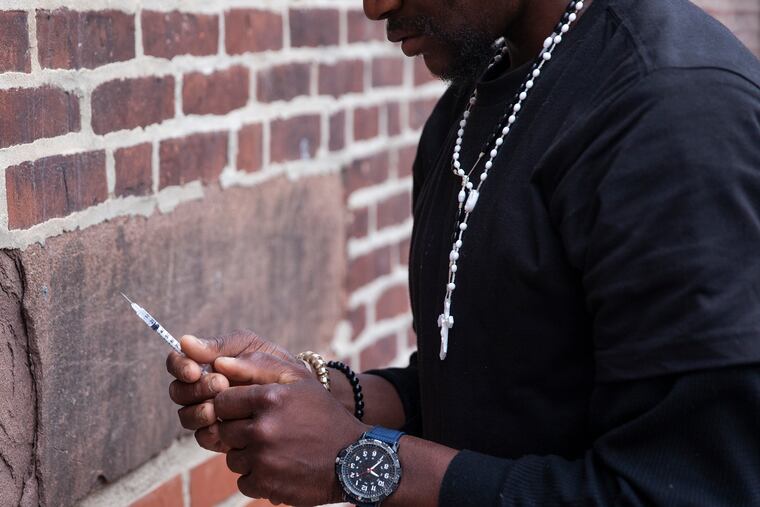

Philly’s overdose deaths rose again in 2019, especially in black and Latino communities

Overdoses killed 1,150 Philadelphians in 2019, in the worst big-city opioid crisis in the country.

Overdose deaths in Philadelphia increased by 3% from 2018 to 2019, killing 1,150 residents in the nation’s worst big-city opioid crisis.

Fatal overdoses had declined between the peak of the epidemic in 2017, when 1,217 people died of drug overdoses, and 2018′s toll of 1,116, sparking hope that deaths might continue to decline. Wednesday’s announcement by the city health department extinguished that hope.

For years, an epidemic rooted in the prescription drug explosion was widely regarded as a bigger problem for white people. Now, the death rate among the city’s white residents, while still high, has declined for two years.

But black and Latino communities saw alarming increases in overdose death rates in 2019. It’s a development that echoes the health disparities on display in the coronavirus pandemic, which has disproportionately affected minority populations.

“It’s heartbreaking. It’s a lot of people dying in Philadelphia,” said José Benitez, director of the public health organization Prevention Point Philadelphia in Kensington, long the heart of the city’s drug crisis. “We need to do more work.”

Fentanyl, the powerful synthetic opioid that has replaced most of the city’s heroin supply, is again behind most of the overdose deaths, he said. But deaths involving opioids alone have dropped. The largest portion of drug deaths, nearly 48%, were due to a combination of opioids, which are depressants, and stimulants like cocaine and methamphetamine.

Some people who use drugs say that use of opposites can counter the extreme sedative effects of fentanyl, but it’s unclear how many people are intentionally combining opioids and stimulants, and how many are unwittingly consuming drugs contaminated with fentanyl.

“We are making progress among people who use only opioids,” said Thomas Farley, the city’s health commissioner. “But that’s been more than surpassed by the rise in deaths in a different population: people who are using both fentanyl and cocaine, or fentanyl and methamphetamine. And that population is more likely to be African American and Hispanic.”

The death rate among whites declined by 22% in 2018 and by 3% in 2019. But the black overdose death rate dropped just 14% in 2018, and increased by 14% in 2019. And overdose death rates among Hispanics dropped by 9% in 2018, and spiked by 24% in 2019. The rise means that overdose death rates among whites and Hispanics are now about even.

More data are needed to determine exactly what’s behind the spike in the death rate among minority populations, said Eve Higginbotham, vice dean for diversity and inclusion and a professor of ophthalmology at the Perelman School of Medicine of the University of Pennsylvania. But structural inequities in society clearly contribute to worse health outcomes for people of color, she said.

Unemployment rates in Pennsylvania for black and Hispanic residents are higher than that of whites, Higginbotham said, and have long been linked to “diseases of despair” like addiction.

“It may be simplistic to say that it’s just unemployment, but that’s a big contributor to this,” she said. “It’s the canary in the coal mine, just like we’re seeing with COVID-19 — it’s challenges with access to care, structural discrimination in health care. And if you overlay that with insufficient mental health providers in the community at a time when people need some support, particularly with a rising unemployment rate, it’s just a formula for despair."

Benitez said the city must work harder to reach communities of color. Access to treatment and distribution of the overdose reversing drug naloxone have improved, but as the new report shows, more must be done.

The contamination of most of the city’s heroin supply with fentanyl has led to more overdoses in general. But now, health officials are seeing fentanyl overdoses in people who in the past did not use opioids — because the synthetic also is being taken in combination with drugs like cocaine, sometimes without the users’ knowledge.

“Cocaine-related deaths have been more common in African Americans and Hispanics than whites in the past,” Farley said. “What we’re seeing now is that fentanyl has gotten into that population.”

He said Prevention Point has been warning its clients that all drug users, not just those who use opioids, are at risk of overdose from fentanyl, and is encouraging them to test their drugs with strips that detect the presence of fentanyl.

Farley said it is likely that some people don’t realize there is fentanyl in the cocaine they are using, but others are deliberately using fentanyl with stimulants. It’s unclear which trend is driving the most deaths.

“There definitely seems to be a disconnect between what people think they’re buying and what’s found in their toxicology if they die or their drugs are tested. There are a lot of really dangerous cutting agents on the scene,” Kendra Viner, the health department’s opioid surveillance program manager, said in an interview last year about the rise in stimulant use in Philadelphia.

Farley said the city’s goals remain the same: get more people into treatment, especially medication-assisted treatment, and promote harm-reduction practices like needle exchanges and naloxone distribution for people who aren’t ready to stop using drugs.

“We have been addressing this mainly as an opioid problem,” he said. “We now need to address it more broadly. The fundamental principles don’t change. What differs is the nature of how we talk about it. Instead of only talking about opioids, we’re going to have to talk about cocaine, and we have to talk about people who have been using cocaine for a long time who are starting to add fentanyl to the mix."

That outreach has been complicated by the coronavirus pandemic, he said. “There’s outreach to people on the street, but it’s not at the level it was before. It’s much more difficult for us to get the message out.”

Farley said it’s too soon to tell whether overdoses have increased during the pandemic, but the city has seen no evidence that they have decreased since the city’s lockdown began in March.

“We have these two crises happening at the same time. We need to focus on both,” he said.

Doses of naloxone, the overdose-reversing drug, are available for people who use drugs and those directly connected to them, through a mailing program run by the addiction outreach and activism group SOL Collective and Next Naloxone. Visit naloxoneforall.org/philly, watch a short training, and enter your address to receive a dose.