Atlantic City residents split as ‘Big Casino’ bankrolls effort to change their city government

Used to Boardwalk protests and strikes against billionaire casino owners, the city's Local 54 casino workers are now entering the civic conversation in unprecedented ways. Residents vote March 31.

ATLANTIC CITY — What does Morris Bailey want?

The elusive owner of Resorts Casino Hotel has spent more than $179,000 trying to change Atlantic City from a government run by a nine-person ward council and an elected mayor to one run by five at-large council members and a professional city manager. Unions have kicked in an additional $42K.

But the question of who really runs Atlantic City is unlikely to be settled by the March 31 referendum, no matter which side wins, in a battle that has broken along confusing lines in this casino city that always seems to be under siege from outside and inside interests.

In this case, the Vote Yes group is dominated by the red “One Job Should Be Enough” shirted members of UNITE HERE Local 54, the storied Atlantic City casino workers union, which counts about 1,500 members who live in Atlantic City itself, 1,000 of whom are registered to vote.

In a city accustomed to vocal Boardwalk protests and fearless strikes against billionaire casino owners, this referendum battle has these casino workers, many Hispanic, entering the civic conversation in unprecedented ways.

“It’s about time Local 54 got involved," said former Mayor Don Guardian, who has endorsed the change, putting him in opposition to current Mayor Marty Small, despite a former alliance in an unsuccessful battle to fight off a state takeover, now in its fourth year.

“They’re the breathing heart of Atlantic City,” he said.

Bob McDevitt, the president of Local 54 who has been spearheading the effort, along with Bailey and former State Sen. Ray Lesniak, who personally lent the effort $10,000, said his members are ready to make their voices heard in city government. The union’s PAC donated $10,000 to the Vote Yes PAC, “Atlantic City Residents for Good Government.”

“We had a lost decade from casinos in PA in 2006 through fights with billionaires, [Hurricane] Sandy, [casino] closings, and finally the showdown with [Trump Taj Mahal owner] Carl Icahn in 2016," McDevitt said. "We lost 40% of our members. We were so busy treading water that we couldn’t intervene with the politics while the city was cratering. That’s changed and now we’re able to engage.”

The Vote No group has been fueled by a familiar alliance of the city’s civic associations, elected officials, and organizers from Food & Water Watch, back in town for a second time in recent years warning about water privatization.

Those groups banded together previously to fight the state takeover and block any attempt to sell the Municipal Utilities Authority. Back then, the city was on the verge of bankruptcy, reeling from multiple casino closings that decimated its tax base. (The proposed new form of government would not permit “initiative and referendum,” which the group said makes the water utility vulnerable to being sold).

On a recent Saturday inside St. Nicholas Greek Orthodox Church on Atlantic Avenue, residents said they feared the consolidation of power in a system comprising at-large representatives and a city manager who could quickly gain tenure.

Once again, they said, they believe their power to represent themselves was being undermined. Some saw it as an attack on a black power base in Atlantic City, one that has spent decades trying to get a share of casino tax revenue that was supposed to go toward the city’s economic revitalization.

To change the government, the referendum must be approved by at least 1,869 people, equivalent to 30% of the number of people who voted in Atlantic City in the last general election.

About 3,000 people signed a petition to get the matter on the ballot, though a portion of those signatures are in dispute. In traditional Atlantic City fashion, a court challenge will be heard March 9.

“I think we are going to lose more than we will gain,” said retired social worker Libbie Wills, president of the First Ward Civic Association who lives in the Inlet neighborhood. “I don’t like they had to go back to 1923 to come up with the form of government.”

She said the ward system — six of the current council are elected by dividing up the 48-block-long city into six wards — provides better accountability.

“This is what we’re going to lose: community representation,” she said. “We would be voting at large for five members. All five people could technically come from the same household.”

Ex-mayor awaits sentencing

A déjà vu paranoia has set in around this city, which has repeatedly seen mayors arrested on corruption and which is awaiting an April sentencing of the most recent, Frank M. Gilliam Jr., who pleaded guilty in October to stealing from a youth basketball charity he founded.

People worry: Is this effort really about Camden County and power broker George Norcross trying to deepen their foothold into deep South Jersey? Is it about Big Casino’s desire to take over city government for its own ends, further eroding a historically fragile balance of power between casinos and residents?

Is it, again, about the water? (Lesniak, on the phone, shouting, insists not. “I do not support privatization of water authorities!" Lesniak insisted. And historically, he’s no Norcross ally, he says. “That has nothing to do with what we’re doing!” he yells. "Why would the casino workers want to privatize the water companies?”)

Norcross has denied any involvement in this effort. Morris Bailey has told people he wants to make a major investment in town but worries about the government and the condition of the city.

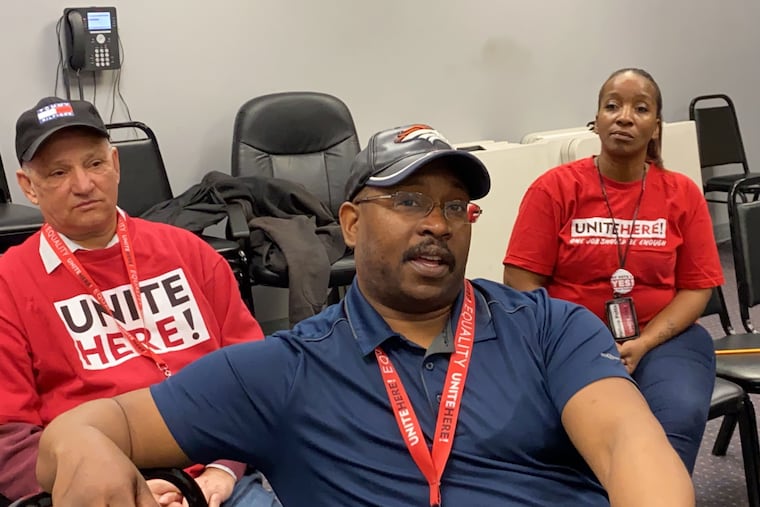

At Local 54′s Pacific Avenue headquarters, whiteboards are devoted to explaining the differences between the two systems of government. A group of casino workers has gathered to explain why they want a new form of government.

There is a buffet beverage server, a couple of people in housekeeping and environmental services, a bar porter. A couple own homes and say taxes are too high (residents got aggravating new assessments this week, which Small acknowledges could complicate efforts to stave off the change of government); others are renters.

Together, they present a picture of the middle-class core of Atlantic City — black, Hispanic, South Asian — that legalized casinos were supposed to strengthen and expand. Most casino workers don’t live in the city at all.

Rodney Mills Jr., a buffet beverage server at Tropicana born and raised in Atlantic City, said the government in Atlantic City has let him down again and again.

“When the storm [Sandy] hit, where were they?” Mills said. “As union members we take care of ourselves. It’s a gamble either way, but one I am willing to take.”

McDevitt said the current system has benefited “20 families,” an entrenched political power base he likens to “a cabal.”

Like former Mayor Guardian, he says he’s not personally interested in being the city manager under a new system.

James Henry III, an environmental services worker at Tropicana, says knocking on doors, he hears the argument that the effort is aimed at taking power away from the city's black residents.

“I hear that a lot: ‘We have to keep black people in there,’ " he said. "My response is, even if they’re doing wrong? They want to use race as part of their power.”

Cristian Moreno-Rodriguez, a Latino activist and organizer, was initially part of the effort to change the government. But he said he now is opposed to the change, and believes the effort has exploited racial and ethnic divisions.

"I feel they pitted us against each other for their reasons and not for mine,” Moreno-Rodriguez said. “Regardless of what happens, we still have long-standing problems that have to be addressed. This petition is a symptom of much larger problems: historic lack of representation among Latino communities, us feeling like our voices aren’t being heard.”