The story of the second woman executed in Pa. history shows why the death penalty must end | Opinion

Seventy-five years after the death of Corrine Sykes, why do chance and politics still determine who lives?

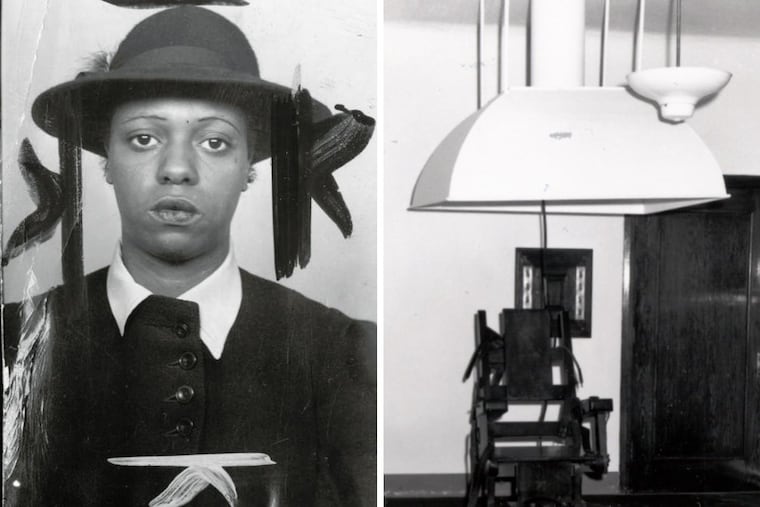

Seventy-five years ago this month, Corrine Sykes walked “the last mile” to Pennsylvania’s electric chair in a gray jumper and white bobby socks. She was a 22-year-old African American housemaid with a mental age of 8.

She was convicted of sinking a large kitchen knife into her new employer’s heart, then dismembering her finger in a frantic struggle to snatch a two-karat diamond ring. Sykes naively confessed to Freeda Wodlinger’s murder: “After I stabbed her, I took the rings off her fingers. I sure like jewels.”

The crime

Harry Wodlinger played hooky from his Center City real estate office on the afternoon of Dec. 7, 1944. He bounded up the 20 steps to his house on leafy North Camac Street minutes after Sykes hurried down them.

» READ MORE: It’s time for Pennsylvania to abolish the death penalty | Editorial

His plan was to drop off the meat his wife wanted for dinner and grab his golf clubs. He was going to play a round with his buddy Irving Weingrad, who was waiting in the car at the curb. As he climbed the steep steps, an alarm went off in Wodlinger’s head. He spotted his front door ajar on a day when the temperatures never climbed above 46. Then he heard Susie, his mop-haired terrier, barking from the basement.

He found his well-dressed wife sprawled on the floor of the bathroom. The room was a fight scene. Along with his wife’s rings, a string of pearls, and $100 cash, the Wodlingers’ new live-in maid was missing.

Fear seeped across Philadelphia’s tonier neighborhoods, where housemaids were in high demand in the days before automatic washers, dryers, and dishwashers. The case reverberated on the city’s African American blocks, too, because domestic work was a support beam for Black neighborhoods. Unskilled men might be furloughed whenever the economy dipped, but a well-to-do wife would keep a good maid because it was too time-consuming to train a replacement.

After Sykes confessed, detectives found her bloodstained tan skirt and turquoise sweater at her boyfriend’s apartment. After 17 arrests, the boyfriend knew a thing or two about talking to police. He said he didn’t know Sykes had killed anyone when she changed outfits at his place. “News to me,” he said.

Sykes’ relatives said the boyfriend orchestrated the theft. If he did, he was savvy enough to send Sykes solo and leave no fingerprints of his own.

Alamena Sykes, the suspect’s mother, told reporters, “Corrine was so tender and mild, but she wasn’t very smart, and she didn’t use the brains the Lord gave her.”

Word percolated around the city that Sykes’ school principal had recommended she be institutionalized years earlier, but no institution in Philadelphia would take a Black child.

The trial

Raymond Pace Alexander, the city’s preeminent African American attorney and later its first Black judge, represented Sykes. He never asked for an acquittal. He asked the jury to consider Sykes’ case as a social problem and sentence her to life without parole.

During the trial, Judge Vincent Carroll interrupted Alexander’s defense, overruled his objections, and, when Alexander got the boyfriend on the stand, Carroll advised the man not to answer. The jury took 301 minutes. The verdict: guilty punishable by death. Higher courts brushed off Alexander’s appeals.

Philadelphia Tribune columnist Elijah Hodges called Alexander a “bronze Clarence Darrow.” He said he had two strikes against him from the start, though. First, a Black woman accused of murdering a white woman. Second, the evidence against her.

Today

Sykes was only the second woman electrocuted in Pennsylvania. Six were sentenced to die in the chair before her, but five got off with life, including a white woman with intellectual disabilities. She had smothered her own baby so she could go to parties.

» READ MORE: Pa. could enforce death penalty when Gov. Wolf leaves office | Opinion

Why one woman and not the other? Lives should not be left to caprice and the emotions of the moment.

Former District Attorney Lynne Abraham pressed 108 death-penalty convictions. Current District Attorney Larry Krasner vows never to seek the death penalty. Lives depend on a system that could unravel any election day.

Seventy-five years later, why do chance and politics still determine who lives?

Kathryn Canavan is the author of “True Crime Philadelphia: From America’s First Bank Robbery to the Real-Life Killers Who Inspired Boardwalk Empire,” coming Nov. 15 from Lyons Press.