About 1 in 5 Pennsylvania adults are caregivers, and they’re not OK | Opinion

If you aren’t already a caregiver for a friend or family member who is disabled, elderly, or in poor health, you may be soon.

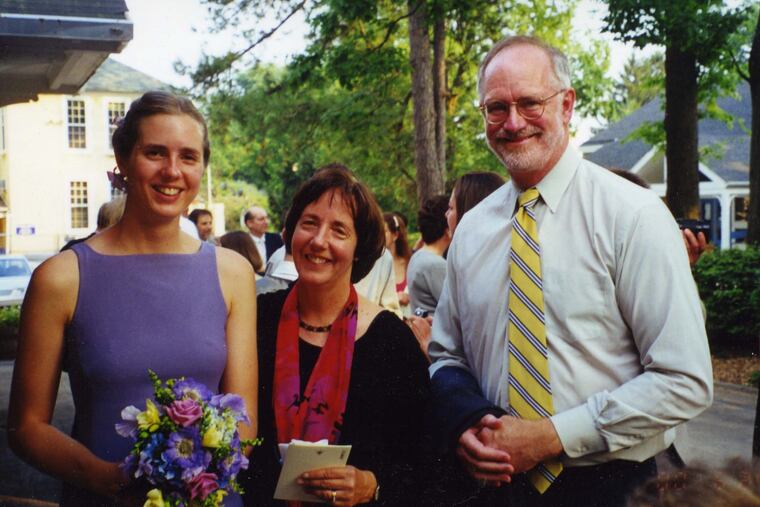

For 15 years, I was a caregiver. Not as a job, but as a daughter of dying parents.

It started around 2005 when my mother began having trouble walking. As an only child, I moved back to Wyndmoor from New York City, where I had been working as a journalist, so I could help out. When she was diagnosed with ALS, I became her full-time nurse and confidant as she processed her rage and despair about leaving the world before she was ready. Immediately after her death in 2007, my father began having trouble speaking, and was diagnosed with dementia; he died in September.

My family situation was fairly unique. But about one in five Pennsylvania adults are caregivers, meaning they regularly take care of a friend or family member who is disabled, elderly, or in poor health, with that number likely to increase. So if you aren’t a caregiver, you may be soon.

» READ MORE: When my son was shot and paralyzed, I learned how broken Pa.’s home care system is | Opinion

Taking care of my mom was all-consuming; my life essentially stopped until hers did. But my dad lived for 13 years with dementia, and the extra responsibility was like the water level of a bucket under a dripping faucet, slowly rising over time. It started small — accompanying him to doctors’ offices, hiring someone to check on him and do small errands — but steadily grew to where I had to make time for him every day. In my 30s and early 40s, while my friends were getting married or promoted at work, I was calling the Alzheimer’s Association’s 24-hour helpline, researching nursing homes, and fighting with insurance providers. Sometimes it felt like I was drowning.

Under normal circumstances, taking care of a sick or dying loved one is grueling physical and emotional work. Under COVID-19, it’s even harder, as the pandemic has worsened a shortage in professional caregivers, shifting more of the burden onto family members (mostly women). Not surprisingly, unpaid caregivers’ mental health has suffered during the pandemic, and they are significantly more likely to report anxiety or depression compared with adults not in those roles. Family caregivers need more help than they are getting.

During my father’s illness, when I wasn’t with him, my mind was. My phone was always charged and nearby, so I could spring into action in case another emergency arose. The staff at the Chestnut Hill Hospital ER started recognizing me. Over the years, I watched my active, upbeat father disintegrate into an angry, confused man who screamed in my face.

» READ MORE: The hope brought by the COVID vaccine is bittersweet for those of us already grieving | Opinion

I couldn’t take jobs that required long hours or travel. I stuck with supervisors who tolerated me disappearing for hours in the middle of the day for dad’s doctor appointments, or suddenly dropping off the planet for a week because he fell. In 2010, I was forced to resign from a job I loved because the company decided to move to New York.

I was lucky — most of my caregiving didn’t take place during a pandemic. A Pittsburgh study of unpaid family caregivers from April to May 2020 found more evidence their mental health is suffering, and they have worried more about money since COVID-19. A CDC study of caregivers in COVID-19 found that half of people who were both parenting and taking care of ailing loved ones — which was me, for years — said they had seriously considered suicide in the last month, an eight-fold higher rate than among people with neither of these added responsibilities.

Many family caregivers lost home care help during the pandemic. I honestly don’t know how they managed without the amazing aides who frequently came to my rescue. I also had friends and family who would visit my ailing parents, giving me a break — this option, too, went away during COVID-19. You can now get walk-in vaccines in Philly, but those don’t reach homebound patients and their caregivers, some of whom have waited months for shots.

“You may see caregivers going to work, grocery shopping, or meeting a friend. But inside, they are drowning.”

Pennsylvania and New Jersey offer some help to some family caregivers, such as cost reimbursements, meal delivery, and supplies. Unpaid family caregivers always need respite, which adult day centers (also closed during COVID-19) can provide. Thankfully, this month Gov. Tom Wolf signed a bill that removes some financial caps on what family caregivers can receive; the previous monthly spending limit — $500 — hadn’t changed since 1993, and bought very little time off for family caregivers. President Joe Biden’s American Jobs Plan may also help by providing additional federal support for long underappreciated paid caregivers, which could ease the home care shortage.

Besides help with finances and logistics, unpaid family caregivers need emotional support, now more than ever. That starts with acknowledging the burden they carry every day. So consider, as you walk the streets of the city, that one-fifth of the people you pass have an extra responsibility — and in that moment are most likely worrying, planning, and anticipating the next medical crisis they know is coming. They may be going to work, grocery shopping, or meeting a friend. But inside, they are drowning.

Alison McCook is a writer based in Wyncote. @alisonmccook