Do we still need presidential debates? | Pro/Con

While debates still draw millions of TV viewers, some wonder if they’ve become less useful and too performative, especially as the internet makes it easier for campaigns to connect with voters.

On Tuesday, President Donald Trump joined Democratic presidential candidate and former Vice President Joe Biden in the first debate of the 2020 general election, one marked by interruptions, a lack of decorum, and President Trump’s refusal to condemn white nationalist groups, including the Proud Boys.

According to a Wall Street Journal/NBC News poll released on Sept. 20, more than 70% of respondents indicated that the debates won’t matter much this election cycle. Forty-four percent indicated the debates won’t matter in the slightest. In the current era of hyperpolarized and media-driven campaigns, some may claim that debates are no longer necessary. However, presidential debates still drawer tens of millions of viewers, according to recent data from the Pew Research Center, which points to the likelihood that voters are still interested in hearing from candidates in this time-honored format.

The Inquirer turned to two scholars to debate: Do we still need presidential debates?

No: Presidential debates entertain, but they don’t inform.

Bz Joseph Shieber

In this unusual campaign season shaped by the coronavirus pandemic, few Americans, I suspect, have missed the rituals of fund-raisers, conventions, and rallies. So why are we hanging on to the pointless tradition of presidential and vice-presidential debates?

Debates don’t serve any of the audiences who might tune into them. Those who follow politics already know the candidates’ track records and positions, so the debate doesn’t provide any salient information, just noise. And focusing on the effect of debates on undecided voters distorts the discussion of the candidates in ways that damage substantive coverage of political issues.

If they’re watching the debates at all, uninformed or undecided voters are almost certainly focused on the wrong signals. Appreciating who refrained from perspiring, who wasn’t sighing annoyingly, or who had the snappiest one-line rebuttal doesn’t actually tell voters anything about who would promote policies that best represent those voters’ — and the country’s — interests.

Debate performance doesn’t reveal a candidate’s deeply held moral principles or their selfless pursuit of the country’s well-being over one’s own ambition. For evidence, look no further than Princeton University’s 1992 North American Debating Championship Top Speaker, National Championship Top Speaker, and Speaker of the Year, Ted Cruz.

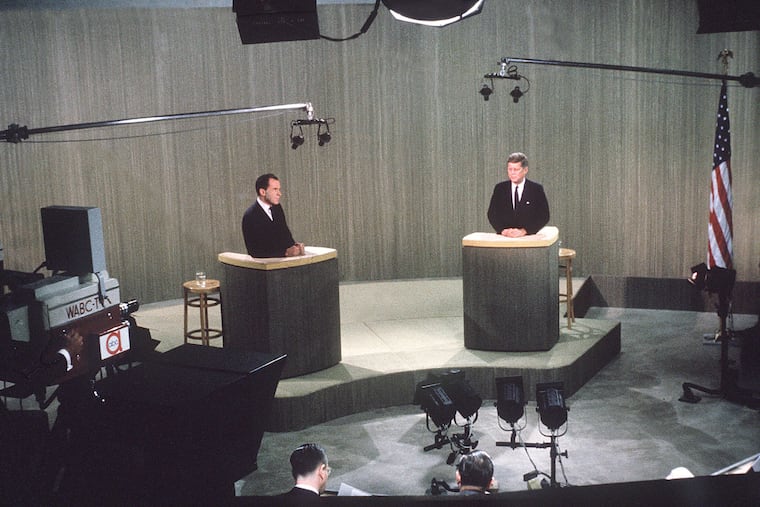

Debate skill doesn’t equate to a smarter or more experienced candidate, either. In the three most frequently cited influential debates, the sick-looking and sweaty Nixon was almost certainly more intelligent than Kennedy. As for sighing Gore vs. Bush and youthfully inexperienced Mondale vs. Reagan? It’s not even close.

Nor do presidents have much occasion to deploy their debating skills on the world stage for the good of the country. It wasn’t Reagan’s one-liners that endeared him to Maggie Thatcher, but their shared love of deregulation and conservative economic principles. And it wasn’t W’s folksy charm that won Tony Blair’s support for the war in Iraq, but a shared sense of quasi-religious purpose and the horror over 9/11.

While it may be true that debates demonstrate which candidate is better able to communicate his or her core beliefs to the public, this is no virtue.

First, it reinforces the view of the political-media establishment that stories on political style and the “state of the political race” are worthwhile topics for endless column inches of bloviating. Second, candidates have plenty of other opportunities to communicate their core beliefs to the public. That’s what campaigns are for.

Presidential debates are certainly not without entertainment value, but that’s just further evidence that we don’t need them. What is entertaining about the debates is the armchair political psychology. It’s watching “your” candidate performing while asking yourself, not, “How is she doing?” but, “How will a few tens of thousands of uninformed voters in Wisconsin, Michigan, or Ohio perceive that she’s doing?”

If you think that a series of televised debates is an important hurdle in choosing a president, then don’t be surprised if the coverage of the “horse race” dominates discussion of policies and ideas. Don’t be surprised if complex solutions to complex problems fail to translate into 15-second soundbites. And don’t be surprised when the real loser of the debate is the audience.

Joseph Shieber is an associate professor of philosophy at Lafayette College.

Yes: Presidential debates set agendas and help undecided voters.

By Brandon Koenig

Debates matter for undecided voters. While the poll numbers indicate a record level of interest in this year’s presidential campaign, 11% of voters are still undecided, more than Joe Biden’s lead in the same poll. For these voters, presidential debates might offer the cleanest opportunity to compare the two candidates position by position.

Debates matter for a second minority of voters — the organized and the powerful. One of the greatest victories of our elites is convincing citizens that voting once every two or four years is enough to be a responsible citizen. While many of us engage in this “set it and forget it” style of politics, real policy change happens in between elections.

Wealthy players will watch the debate to ensure that their preferred candidates do not veer too far off message. Social movement actors will take notes about the promises — or threats — made to their constituencies. Both groups will follow how the messaging plays out among the citizenry and begin to plan how to hold the president accountable or push them to act in the coming year.

» READ MORE: How Miami plans to host an October presidential debate amid a coronavirus pandemic

Debates are a key site of this work, as candidates lay out the contours of acceptable speech and behavior among supporters. Trump voters will learn how to best defend his record on race, while Biden supporters will see how to thread the needle on Black Lives Matter.

But for the rest of us, debates are something of a spectacle. We don’t tune in for a measured discussion of policy proposals (which candidates don’t offer, anyway). Instead, we tune in to watch our preferred candidate denigrate our opponents and elevate ourselves.

For many voters, this election is about the future, the heart and soul, of the United States. The Biden supporters I know describe a country slowly slipping into ethnonationalism and fascism. For my Trump-supporting colleagues, a common belief is that a Biden victory will bring in an era of communism and the destruction of their way of life. With such stark contrasts, it would be a mistake to assume that a debate structure could at all influence committed partisans from one side to the other.

As political scientists Christopher H. Achen and Larry Bartles tell us in Democracy for Realists, “Even the most informed voters typically make choices not on the basis of policy preferences or ideology, but on the basis of who they are — their social identities.” Debates are one moment in the continual renewal of American democracy, but not through romanticized notions of sober reflection or free and fair elections. Rather, the performance of the candidates in the debate help Americans to reconsider and solidify their connection to the social groups that make up their individual identities. Who am I, and who am I with? In turn, who am I not, and who am I against?

The spectacle of presidential debates allows candidates ample room to describe what it means to be properly American. The starkness of the differences, amplified by the format of the debate, allow voters on both sides to better understand what kind of Americans they should want to be. The debate will also illustrate why opponents are villains and undeserving of the title of American. For those that think this dynamic is a problem, the politics of elections and parties clearly offer no path toward a solution. Until then, tune in and enjoy the show!

Brandon Koenig is an assistant professor of government and public policy at Franklin & Marshall College.