A new book about Kensington issues an urgent call to action for a long-neglected neighborhood

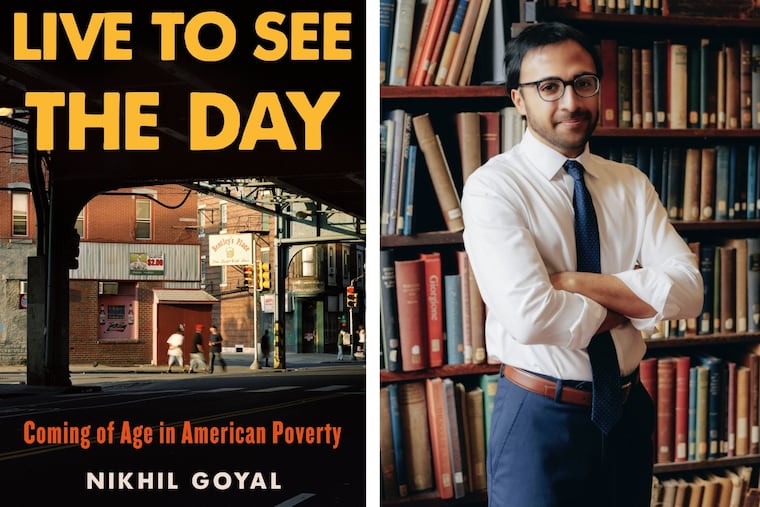

In "Live to See the Day: Coming of Age in American Poverty," author Nikhil Goyal focuses on young people growing up in one of Philadelphia's poorest neighborhoods.

In his new book, Live to See the Day: Coming of Age in American Poverty, sociologist and policymaker Nikhil Goyal draws on a decade of on-the-ground reporting in Kensington for a harsh coming-of-age story.

Against the backdrop of the poorest neighborhoods in the nation’s poorest big city, Goyal, 28, who until recently served as senior policy adviser on education and children for Sen. Bernie Sanders for two years, introduces us to three Puerto Rican students determined to beat the odds: Ryan, who makes a fateful decision that traps him in the juvenile justice pipeline; Emmanuel, forced to navigate his queerness alone when he is rejected by his family; and Giancarlos, a casualty of a deeply flawed school system.

It is a gripping, if familiar, story of crushing obstacles that include hunger, housing insecurity, and drug addiction.

But it is also a call to action aimed at city leaders who have not done nearly enough to address historical neglect and a country that could change policies and save lives.

I spoke with Goyal recently about Kensington, the crisis of disengagement among Philadelphia’s youth, and what can be done to improve the lives of the city’s most marginalized.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

I approached your book with some trepidation, considering how often Kensington is used as a spectacle or a prop, but your book did neither.

I’ve been a longtime organizer and activist, and so my writing and my reporting hopefully honors the social movements and the ideologies behind them. It was very important for me to avoid parachuting in — the one-day, one-week style where you go in and talk to a few people and then characterize an entire neighborhood.

You’ve spent time in Philadelphia, but this was your first time immersing yourself in Kensington. Why did you decide to base your book there?

I was interested in looking at the high school dropout crisis, and I had been in touch with Andrew Frishman, who runs an organization called Big Picture Learning. I asked him to suggest a couple of schools for me to visit and one was El Centro de Estudiantes. This was back in 2015, and I was just about to go to grad school. I thought I was going to write a story and that would be it, but after spending time at the school, I realized that to look at the high school dropout crisis and educational inequality in a more systematic way, we really needed to account for economic and social systems to genuinely understand the lives of these young people and their families.

Tell me about your process and how you made the necessary connections.

I conducted hundreds of interviews, and not just with the kids. They would take me around to their blocks and I would talk to their neighbors. I would sit in parks and chat up people to make sure I was fully understanding folks’ experiences and how they were dealing with certain challenges and issues. I also tried to tie it all to history and to show that there’s a series of policy decisions that were made that put these young people and their families in the conditions that they’re in today. The crisis in Kensington didn’t come about by accident. There were deliberate, systematic policy choices. And so I thought it was important for me to marry these young people’s stories with the social structures that undergird their lives. Without that, it seems we can’t do anything about it — and we can.

But it didn’t end there, right? You took your experiences in Kensington with you when you worked for Sen. Sanders.

I worked for Sen. Sanders for two years, and my experiences in Kensington were at the core when I was working on policy because I knew people who were deeply underserved by policy, and I believed there could be better policies that could transform their lives. I didn’t just want to report and write a book; I also wanted to try to make their lives somewhat better.

You talk in the book about policies and legislation that didn’t go far enough, but can you give an example of something you worked on that had a direct impact on young people and families like those you met in Kensington?

When we expanded the child tax credit in 2021, one of the things I knew from my reporting was that there are millions of people in this country who don’t file taxes. And so the IRS and other government agencies have almost no way to reach them to get social benefits to them. I talked to several young people and families during that time, and I knew they would have difficulties navigating that bureaucracy of getting those benefits. Those conversations informed my policymaking where we actually got language in the draft bill where we would provide funding and support for Social Security, the IRS, and other government agencies to share data. If, say, somebody is on SNAP, that data should be easily shared with the federal government and other entities so that they can identify who is not getting the benefits that they are eligible for.

We’re just months away from electing our 100th mayor. What advice can you offer the city’s next leader to improve the lives of young people and families like those you met in Kensington?

I think the most tangible thing that the new mayor can do is address the youth disengagement crisis. What are we going to do to expand summer and after-school programming? What are we going to do to make sure that kids can get to school safely without getting shot? What are we going to do about making sure that our school buildings and our recreation centers are open extended hours and on the weekends? What are we doing about mentoring programs? Those tangible efforts would be enormously helpful, and they can help a city thrive. The challenges are certainly daunting — the homicide crisis, the urban violence crisis, the crisis of poverty and inequality, those all exist. But at the very least, you start with young people, with children and families, and provide them with the building blocks for a dignified life.