Beware, baseball: Keep bickering and many of your fans will not return in 2021 | Bob Brookover

During elongated negotiations with the players union, baseball owners have estimated that 40% of their revenue comes from attendance. History tells us that failed negotiations can cause fans to lose interest and stay away from the ballpark.

Business was booming at beautiful Veterans Stadium and across baseball in 1993.

The Phillies, on a worst-to-first run to the World Series, drew more than 3 million fans for the first time in franchise history. With a major assist from the addition of the expansion Colorado Rockies and Florida Marlins, the average attendance across baseball rose above 30,000 per game for the first time.

Attendance per game continued to rise in 1994 and so did the league’s average payroll. We know, of course, that gravity never seems to apply to the valuation of ball clubs -- even the ones that are poorly run. The game was healthy, the owners and elite players were wealthy, and yet they were about to do something tremendously unwise.

After a 15-inning victory over the New York Mets on the night of Aug. 11, 1994, the Phillies lined up their SUVs in front of the home dugout at the Vet, packed their belongings, and did not return. It was a scene duplicated at ballparks across the country as what would become the longest strike in baseball history began. It led to the cancellation of the World Series for the first time since 1904 and a bogus spring training with replacement players in 1995.

History is not repeating itself right now, but the contentious negotiations between the owners and players union amid a pandemic and booming nationwide calls for social justice reform do look quite familiar. This would be a good time for the owners and players to remember their sport’s history.

After the 1995 strike finally ended following six senseless weeks of that faux spring training, the average attendance fell from a record high 31,256 in 1994 to 25,021 in 1995, a 20% decline despite some deep discounts on tickets. Thanks to a steroid-aided home run race between Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa, attendance rebounded above 29,000 in 1998, but it did not get back above 30,000 until the 2004 season.

The fan animosity following the 232-day strike was wicked.

At the Vet, an opening-day sign in center field offered a mock pardon: We Forgive You Phils NOT! Bring Back Replacements.

_At Shea Stadium, three Mets fans wearing T-shirts with the word Greed on the front threw dollar bills at the players as they ran onto the field. They got their money’s worth out of it, too, throwing a total of $150.

_In Cincinnati, a fan paid for a plane to fly over Riverfront Stadium carrying a banner with this message: Owners & players: To hell with all of you.

_In Detroit, the Tigers’ May 2 home opener against Cleveland was delayed for 12 minutes and Indians center fielder Kenny Lofton said baseballs, whiskey bottles, and even a large metal napkin dispenser were thrown at him from the bleachers. Fans also held up signs that read, Field of Dreams Greed and Strike, Owner$ Win, Player$ Win, Fans Lose.

“Just call it Fan Upheaval Day,” Baltimore outfielder Andy Van Slyke told the Washington Post.

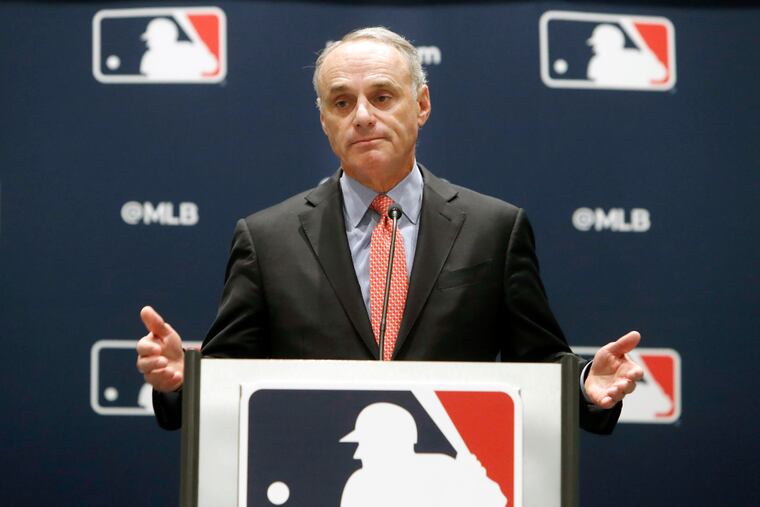

Commissioner Rob Manfred promised before the start of the draft Wednesday that there is going to be a season in 2020, but the failed negotiations between the owners and players have essentially already created a work stoppage beyond the one caused by COVID-19.

The initial plan was to get the games going again around the Fourth of July, but that’s not going to happen, and Manfred made it clear that the delay is about money rather than health protocol. He said that the sides are pretty much in agreement about the health parameters it will take to return.

MLB’s most recent proposal was for a 72-game season and 80 percent pay. It also was tagged with a nasty letter from deputy commissioner Dan Halem and a Sunday deadline. Union chief Tony Clark easily met the deadline Saturday by rejecting the offer and essentially telling the owners there was no reason to even make a counterproposal.

“It unfortunately appears that further dialogue with the league would be futile,” Clark said in a statement. “It’s time to get back to work. Tell us when and where.”

If that’s how this actually plays out we are likely looking at 48-game season without expanded playoffs.

The owners and players should know that nobody is scoring their financial feud at home. Instead, they are mostly ignoring it. Too many other things are happening to keep their attention. As always, the labor negotiations are being viewed as a fight between billionaires and millionaires and the average Joe and Joelle feel nothing but contempt for the participants.

It’s a feeling that also exists among some who work inside the game.

“Greed is an ugly thing,” one National League executive said recently via text. “This game is losing fans of all ages.”

The rage we saw in ballparks 25 years ago after the longest strike in MLB history probably would not be as intense today, but the apathy toward the game is likely to be even greater and that’s something the owners and players should strongly consider. During these turbulent times, the owners have said that 40% of their revenue comes from gate receipts, concessions, and parking. That’s their justification for asking the players to take less than prorated salaries.

There’s no way to confirm that because baseball’s accounting figures have always been concealed from the public and the players union, but the owners nevertheless have to be concerned by the recent attendance trend. The average attendance dipped below 30,000 in 2017 for the first time since 2003, and it has been on the decline for four straight years. That should deeply concern the players, too.

We know, of course, that this is going to be a drastically shortened season without fans and it seems very likely that attendance is going to continue to decline even when fans are allowed back in the ballpark next season. The pandemic-forced rise in unemployment will not help and it’s well-documented that baseball has other issues that need to be addressed.

By Manfred’s own admission, the amount of time it takes to play the game is one of them. Baseball has implemented a few things in an attempt to speed things up, but the average time of games still ticked up to a record-high 3 hours, 10 minutes last season.

By bickering over money, the owners and players are involved in a high-risk, low-ceiling game that we’ve seen in the past. History tells us that if it continues for too long, both sides will lose their most valuable asset -- the fans.