Pa. counties can help voters fix mail ballot errors after state Supreme Court deadlocks on the issue

The six-member court deadlocked, automatically affirming the lower-court decision.

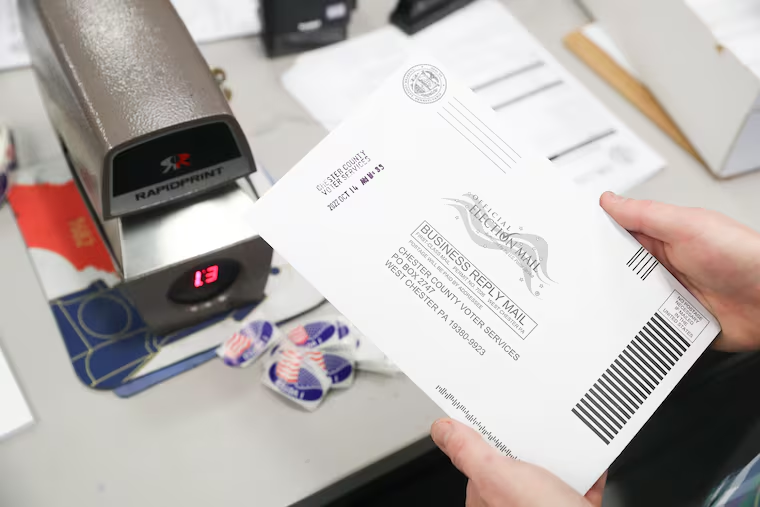

The Pennsylvania Supreme Court on Friday cleared the way for counties to help voters fix errors like missing signatures on mail ballots before Election Day.

A lower court last month denied an attempt to block counties from helping voters “cure” their ballot errors. The state Supreme Court on Friday said it had deadlocked on the appeal of that decision, which means the lower court decision is automatically affirmed.

The high court normally has seven members, but Chief Justice Max Baer died last month. Of the remaining six members, Justices Christine Donohue, Kevin Dougherty, and David Wecht said they agreed with the Pennsylvania Commonwealth Court’s decision that allowed ballot curing to continue. Chief Justice Debra Todd and Justices Sallie Updyke Mundy and Kevin Brobson said they would have reversed it.

The three-sentence order dealt a defeat to the Republican National Committee and other GOP groups, which had filed the appeal in one of the latest fronts in the state’s contentious partisan battle over which ballots should be counted.

Many of the same Republican groups also asked the court to take up a case on whether counties should count undated mail ballots — or those that arrived on time without the required handwritten date on their outer envelope — before Election Day. (The court said Friday that it would hear that case and fast-tracked it, potentially allowing it to rule in time for the Nov. 8 election.)

In the case in which the court deadlocked on Friday, Republicans had asked the justices to bar the practice known as “ballot curing,” citing the lack of any consistent curing policy across all of Pennsylvania’s 67 counties. Some counties allow voters to fix errors while others do not.

Last month, a Commonwealth Court judge sided with Democrats and the Pennsylvania Department of State, which oversees elections. They’d argued that nothing in the law was stopping all counties from adopting curing policies and that denying voters the opportunity to fix mistakes risked disenfranchising lawful voters over minor mistakes made while filling out and submitting ballots.

» READ MORE: Pennsylvania counties can help voters fix problems with their mail ballots, state court rules

But beyond the specific case, the state Supreme Court decision Friday was seen as a boon to Democrats, who are much more likely than Republicans to vote by mail.

And some of the counties that do the most to help voters cure ballots, including Philadelphia, are large and heavily Democratic.

The question of how to handle flawed ballots — like those missing dates or signatures on the outer envelopes, or that have other minor mistakes — has troubled counties since the state implemented no-excuse mail voting in 2020.

Mail voting has a higher error rate — typically about 1% to 2% — than voting in person because it can be more complicated and poll workers help with in-person voting.

» READ MORE: Pennsylvania struggles with how — or if — to help voters fix their mail ballots

Mail ballots submitted without the voter’s signature on the outer envelope, which is required under state law, or so-called “naked ballots” — those returned without the inner secrecy envelope — are required to be rejected.

But in recent elections, some counties have attempted to help voters correct such problems on ballots submitted before Election Day. For example, a county might call, email, or send a postcard telling a voter that their ballot is in danger of being rejected and urging them to visit their local elections office.

Other counties leave contacting such voters to political parties. And more don’t do anything at all, simply rejecting ballots submitted with flaws.

It’s unclear how many ballots are cured statewide in any given election.

Questions surrounding the legality of such curing procedures have been put to the state’s high court before. In 2020, the state Supreme Court denied a request from Democrats to require that all counties implement ballot curing procedures, saying instead such a mandate was “one best suited for the Legislature.”

The case the justices ruled on Friday was partly rooted in the ambiguity of that earlier ruling.

Republicans maintained that the Supreme Court in its 2020 ruling found that only the legislature — and not individual counties — had the power to implement any curing procedures. And since lawmakers had not, they argued, counties shouldn’t be allowed to adopt them on their own.

Democrats insisted that the justices had stayed silent two years ago on what counties were permitted to do, and had simply said in their 2020 opinion that they did not view the court as the appropriate body to implement a statewide policy.

In her ruling last month, Commonwealth Court Judge Ellen Ceisler agreed, noting that the Supreme Court’s 2020 ruling didn’t require curing procedures but didn’t forbid them either.