How a modern public library ended up among Wynnefield’s stately stone homes

Fifty years later, the library is still bringing light and enlightenment into the neighborhood.

During the middle decades of the 20th century, modernist architects produced endless variations of low-slung, flat-roofed buildings. Some were conceived as floating glass vitrines and looked as weightless as a soap bubble. Others were more like shoeboxes, solid and inscrutable from the outside, and firmly earthbound.

The Wynnefield branch of the Free Library is a little of both. Completed in 1964, the building features a staccato run of brick bays along its two main facades, on 54th Street and Overbrook Avenue. But the walls are not as formidable as they might first appear. Each brick section is separated by a narrow window slot. And just below the decorative roofline, a series of large windows forms a clerestory, bringing a soft light into the reading rooms. The alternating rhythm of solid and void gives the facade a lively sculptural quality.

Nestled on the western edge of the city, between Fairmount Park and Bala Cynwyd, Wynnefield developed into a leafy enclave of large stone homes in the early 20th century. Horace Trumbauer, the architect who catered to the Jazz Age’s newly minted millionaires, lived there, as did many prosperous Jews, Catholics, and African Americans who felt excluded from the city’s other upscale neighborhoods. But despite the area’s growing affluence, it lacked a local library.

In the late ‘50s, Wynnefield residents began lobbying the city for a branch of their own. Under the Free Library’s energetic director Emerson Greenaway, the city had been extending its branch system into growing neighborhoods such as the Northeast. In the early ‘60s, the Free Library finally agreed to establish a Wynnefield location at 54th and Overbrook, a transitional corner where the residential neighborhood gives way to St. Joseph’s University and the commercial area along City Avenue.

The Free Library reached out to a firm led by Newcomb Montgomery and Robert Bishop. The pair had just won acclaim for their district health center at Broad and Lombard, faced in flashy, turquoise-colored glazed brick (and now about to be redeveloped by the Goldenberg Group). Reconstituted as Montgomery, Bishop & Arnold, the firm went to work developing a design that would fit into Wynnefield.

Much like that in Chestnut Hill and Mount Airy, Wynnefield’s architecture was defined by the use of a heavy gray stone called Wissahickon schist. The area was originally settled by Thomas Wynne, William Penn’s physician, and his 1689 homestead seems to have been the inspiration for everything that followed. But the architects stuck to their modernist guns and resisted using stone. They chose flat modern brick, instead.

Even though they were breaking from local tradition, the warm, brownish-red brick was still fairly subdued, especially in comparison with the brightly colored blocks the firm chose for the health center. Had the designers not segmented the bays, the expanses of flat brick would have been awfully dull. The design is saved by strong detailing that emphasizes the thickness of the walls. The best feature is the stone band along the roofline, which forms a simplified Greek key pattern and serves as a modernist cornice.

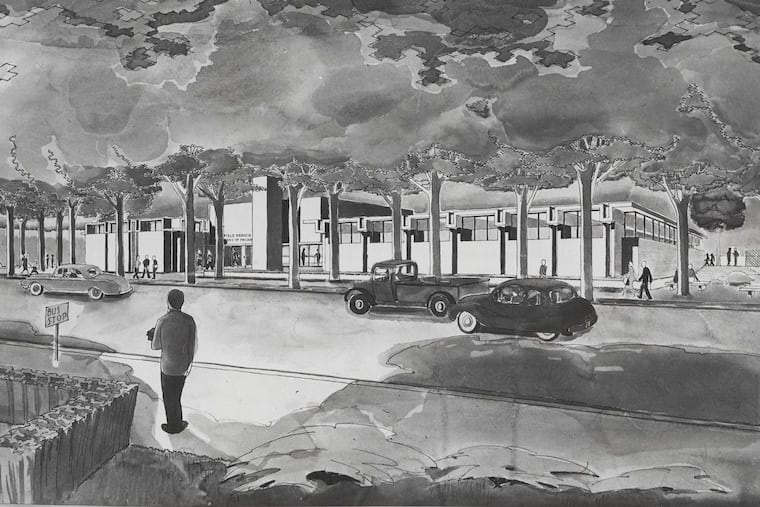

Judging from the early renderings, the architects had more ambitious plans for the site than were actually realized. One model shows an L-shaped building facing an elegant sunken garden. The space, sadly, ended up as a dreary, unlandscaped interior courtyard.

The strength of the design is the way it is organized as a collection of geometric volumes. There are two horizontal wings, each housing a reading room. What was expected to be the main entrance is located at the point where the wings intersect on Overbrook Avenue. The entryway is marked by a monumental brick tower that hovers over the complex, similar to the one at the Northeast Regional Library. At some point, however, access was switched to a less impressive entrance on 54th Street. The Overbrook entrance is now fenced off and used to store trash.

The 54th Street entrance may have been more practical because you can glide in at street level, without having to climb stairs. From the reception desk in the lobby, you can see into both the children’s library and the adult reading room.

Inside the building, the logic behind the exterior arrangement of windows becomes clear. The rooms are bathed in natural light. But because the sun filters in through the clerestory windows, which are partially shielded by brick overhangs, the rays are modulated and there is no glare. When you look down the aisles of shelves, the narrow vertical windows and horizontal clerestories appear to coalesce into a T-shape. You see the same arrangement in many Louis Kahn designs. The influences of other modernist architects, such as Geddes Brecher Qualls Cunningham, is also evident.

Wynnefield has continued to change since the library was built. St. Joe’s has expanded deeper into the neighborhood and 54th Street has become more commercial. But after more than half a century, Wynnefield’s modernist brick library remains a hub of light and enlightenment for the community.