Everyone wants football back, but Timmy Brown’s death is a sign the sport’s dark side remains | Mike Sielski

Brown was one of four former NFL players, all of whom suffered from head trauma from football, who died in less than three weeks.

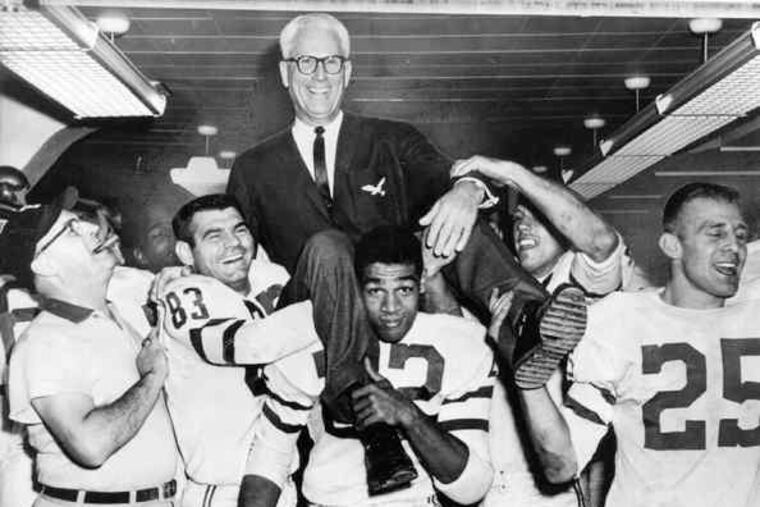

Timmy Brown was still so charming in his final years that he could mask his dementia from just about anyone. Often, he and his son, Sean, would go for bacon and eggs at a coffee shop in Palm Springs, where they lived, and he would tell the stories he had always told – about his 10 years as a star tailback and kick-returner with the Eagles and the Green Bay Packers and the Baltimore Colts, about his careers as an actor and a singer, the supporting roles in M*A*S*H* and Nashville, the celebrity hobnobbing.

The young waiters and waitresses listening didn’t notice, as far as Sean could tell, that Timmy’s anecdotes were becoming circular and repetitive. Why would they notice? The details were too captivating. You played in Super Bowl III, Mr. Brown? You dated Diana Ross? Wow! But Sean knew. Sean had known for a while. He had begun to pick up on the changes in his father in 2006. At first, Sean kept his concerns to himself, because the stories were still wonderful, and his father still told them well.

“I’d be like, ‘You’re telling the Muhammad Ali and Jim Brown one again? OK. I’ll listen. I’ve heard this a thousand times, but it’s Muhammad Ali and Jim Brown, so I’ll listen again,’” Sean said.

But then the tales grew more tangled, and Sean thought back to when he was a teenager, when his dad would get “forgetful and weird and paranoid,” he said. Sean made the connection … and worried. When he was 18 and Timmy was 68, Sean asked him if he would consider having a doctor examine him. The confirmation came a month later. Not only did Timmy have dementia, but he had been suffering from some form of it, the doctor told him, for probably 10 years before the official diagnosis.

Timmy Brown, who led the NFL in total yardage twice, who played one of football’s glamour positions and savored the glamour of Hollywood, who was inducted into the Eagles Hall of Fame in 1990, died on April 4. He was 82. That means it’s possible his brain had been deteriorating for the previous quarter-century, for 30% of his life.

“There’s no family history of dementia,” Sean said in a recent phone interview. “I can confirm it was football-related. I also know that’s not how he would have liked to have been remembered.”

Nor would Tom Dempsey, who was an NFL kicker for 10 years and five teams, including the Eagles. Who was born without toes on his right foot and fingers on his right hand, yet in 1970 boomed a 63-yard field goal, which for 43 years held up as the longest kick in league history. Who was 6-foot-2 and 255 pounds, beefy and stout, and came up in the NFL as an offensive lineman. Who covered kickoffs throughout his career and relished the vicious collisions of that kamikaze role. Who suffered at least three concussions – three, at least. Who had been living with dementia for at least a decade before he contracted the coronavirus in March and died on April 4. He was 73.

Nor would Mike Curtis, who was an All-Pro at linebacker four times in his 11 seasons with the Colts. Who, in a 1971 game at Baltimore’s Memorial Stadium, was so offended and angered that a drunken fan had run onto the field that he clotheslined the man, a moment that has remained an NFL Films fixture ever since. Who “struggled with memory loss later in life,” one obituary said after he died on April 20, and whose family donated his brain to the Brain Injury Research Institute, in Wheeling, W.Va., to determine whether he had the disease chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE. He was 77.

» READ MORE: The day the Eagles’ Timmy Brown scored at Atlantic City’s Steel Pier | An Appreciation

Nor would Vikings guard Milt Sunde, who started 113 games at guard over 11 seasons with the Minnesota Vikings. Who played in two Super Bowls. Who was, his teammate Fran Tarkenton said, “never the biggest or the fastest, but … the smartest and the toughest.” Who died on April 22, having suffered from Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease. He was 78.

Four former NFL players with head trauma or disease, all of them within 10 years of age, all of them dead within three weeks of one another.

Football has long been the country’s true pastime, its civic religion, and even now, as the NFL tries to maintain its routines and conduct its business in the usual way despite the pandemic, it provides the hope that things will be normal again, that autumn will begin and football will begin with it. And before the pandemic reoriented everyone’s focus, the NFL had a good story to tell and sell about the advances made in treating head injuries, in changing the way that players approached and dealt with those injuries and their potential long-term effects.

One of its young stars, Carson Wentz, removed himself from a playoff game in January after suffering a concussion, and his peers understood, even lauded him for it. This was a breakthrough, a sign of progress.

“We as players know what we’re signing up for,” Wentz said.

More of them do, yes, and that’s an encouraging development. But the information available to athletes these days about head trauma wasn’t available to the generations who came before them. The same measure of attention was not paid. In 1967, Timmy Brown lost the entire top row of his teeth on a brutal tackle by Dallas Cowboys linebacker Lee Roy Jordan. The Cowboys might or might not have put a bounty on Brown for that game. Such was the sport then. The men who played it knew there would be damage. They expected a cost. They didn’t expect this reckoning, the darkness that fell over them later.

“He loved his life. He had lived it to the fullest. He felt very proud about what he had done. The dementia thing was the first time I saw him second-guess that, though, where he thought, ‘Man, this is so serious now, and I’m forgetting so much … .’ "

Sean Brown was his father’s caretaker for nine years, and he talked with him about this very subject, about regret.

“He loved his life,” Sean said. “He had lived it to the fullest. He felt very proud about what he had done. The dementia thing was the first time I saw him second-guess that, though, where he thought, ‘Man, this is so serious now, and I’m forgetting so much … .’ That was the first little glimmer of that I ever got from him.

“The through line was typically that he wouldn’t have changed anything. He always talked about that with regard to his knee and his back and his shoulders and all the other ailments he had. The dementia line was the first time he was kind of taken aback. ‘This is more than I realized it was going to be.’ ”

Football might yet return, but these stories haven’t gone away. They won’t. There will be more.