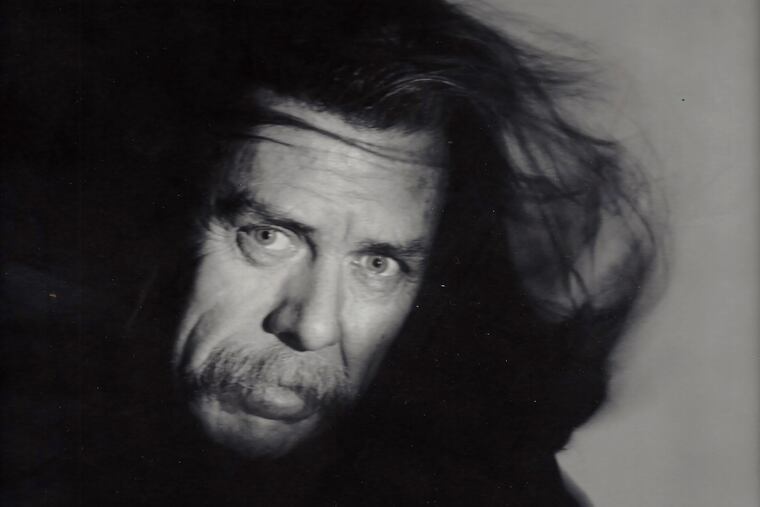

Jim Quinn, whose unapologetic food writing captured 1980s bravado with characters and culture, dies at 85

The prolific Philadelphia journalist and fiction writer died Sept. 30 after a long illness.

“What do you do when a woman comes up naked and asks for a cheese with?” Jim Quinn asked cheesesteak king Frank Olivieri at 3 a.m. one Saturday morning.

“What do we do? Give her a cheese with and say, ‘Next.’ … You think you’re going to make Pat’s Steaks fall down and faint if you take your clothes off? We see it all here.”

That vivid bravado slice of Philly’s unapologetic cheesesteak culture in the early 1980s — with its cinematic snippets of keenly observed banter and unmistakable neighborhood characters — was among the first glimpses Inquirer readers got to read from Jim Quinn, the prolific Philadelphia journalist and fiction writer who died Sept. 30 after a long illness at age 85.

The scene at Pat’s (all 4,000-plus words) eventually become a part of Quinn’s 1983 book, But Never Eat Out on a Saturday Night. But it would be followed by 646 bylines for the next 12 years, most of them for the “Food Life” column in the Sunday Inquirer Magazine. It began with a 1983 visit to Bennie Strano, the fresh-kill chicken butcher on South Ninth Street dispatching Black Minorca birds for stewing (“for flavor, you can’t beat it”) and ended in 1995 with a 10-course farewell banquet at David’s Mai Lai Wah II. And Quinn was still advocating for the freshest ingredients.

On the live tilapia swimming in David’s Chinatown fish tanks: “If you prefer, dead fish … is also available. But live fish, killed and cleaned and cooked to order, is … like trying prime steak after eating supermarket choice grade all your life.”

Quinn’s prose, which became well-known during the previous decade as restaurant critic for Philadelphia magazine, always captured a vital pulse of freshness, a New Journalism-era feast of deft reportage rendered with novelistic dialogue and scenes that revealed a dramatic new stylistic shift at that time in American food writing. At once populist and discriminating, his immersive columns journeyed through the region’s diverse kitchens with social commentary, boundless curiosity, and wicked humor, depicting Philly food life in the moment as it was rather than an idealized vision.

“You want the real story or the B.S. story?” asked Ron Conti in Quinn’s 1985 piece on the origins of Chuck Forte’s frozen stromboli. “The real story is Chuck’s wife didn’t feel like cooking.”

Jim Quinn wasn’t born to gourmet tastes in 1935. He was the Northeast Philly son of an Irish steelworker and a homemaker mom who was “sainted but a terrible cook,” says Quinn’s wife, Daisy Fried, 52.

His antiestablishment streak was evident early when he was suspended from Catholic high school for “preaching communism." A decade later, he enrolled at Temple University where he got plunged into journalism by founding an alternative paper called The Other Temple News. He demonstrated against the war in Vietnam, for civil rights and integration. But it wasn’t until he led a boycott against the school cafeteria’s push to raise the price of coffee by 2 cents that his food writing career began. The publisher of the Collegiate Guide to Philadelphia tapped Quinn to be its restaurant reviewer.

Quinn wrote about other subjects, including politics and language. His 1980 book American Tongue and Cheek took the nation’s “pop grammarians” satirically to task, prompting one target, New York Times columnist William Safire, to say, “Jim Quinn is the Professor Moriarty of language.” A 1979 profile of Philadelphia Daily News columnist Pete Dexter for Philadelphia magazine earned him one of his two finalist nominations for the National Magazine Award.

His love of language made Quinn’s writing about food irresistible, especially as he documented the 1970s restaurant renaissance that transformed Philadelphia’s stodgy scene of fish houses into a more dynamic and quirky modern landscape.

He praised the Philadelphia-style lack of pretense at Le Bec-Fin in 1973, compared to its uptight Gallic counterparts in New York, mooning over the “fat little cylinders” of pudding-like whipped pike quenelles whose texture was “as almost as smooth as a sauce.”

He could also acknowledge the cultural significance of pioneering “war baby” restaurants like Friday Saturday Sunday, Astral Plane, and the Frog without cutting them slack for amateurish cooking.

“To this day I remember his criticism of our hollandaise,” said the Frog’s Steve Poses, still smarting 47 years later. “Hollandaise was taught to me by Peter von Starck (of La Panetière), who knew how to make hollandaise … But (Quinn) had strong points of view. And he was around at an era when restaurants were becoming more interesting and sophisticated. He was up to the task of supporting and adding to that.”

As caustic as his criticism could sometimes be, he could also be very kind, said Daisy Fried, the Guggenheim-winning poet he married in 2000. At dinner once at the Four Seasons, he asked her not to point out that the waiter had accidentally poured a pricey bottle of Vosne-Romanée Burgundy into her half-drunk glass of Spanish red: "He’d go back and kill himself in the kitchen if he knew he’d made that mistake.”

Quinn began to shift away from journalism by 2000 when he married Fried, who teaches at Villanova University. They had a daughter named Maisie in 2007, and he embraced fatherhood again at age 72. He has two other surviving children from a previous marriage, Charlotte Quinn and Michael “Freedom” Quinn.

“He would play with Maisie for hours," Fried says. "Imaginative games, Monopoly, and gin rummy … He was so happy being a dad.”

The retired dining critic ultimately eschewed restaurant meals, she said, for the pleasures of home cooking, with stuffed duck among his specialties. Quinn, who also earned his M.A. in creative writing from Temple, focused more on writing fiction about “left-wing politics and strange sex,” including a two novella book in 2012 called Waiting for the Wars to End.

“He always joked that his (five published books) were ‘worst sellers,’” said Fried. “But he didn’t really care. He would have liked to have been more successful as a fiction writer, but Jim didn’t do regret or guilt very much. He felt that life was for the living, so let’s live right now.”