Who actually has the power to postpone the Pennsylvania primary over coronavirus? And will they agree?

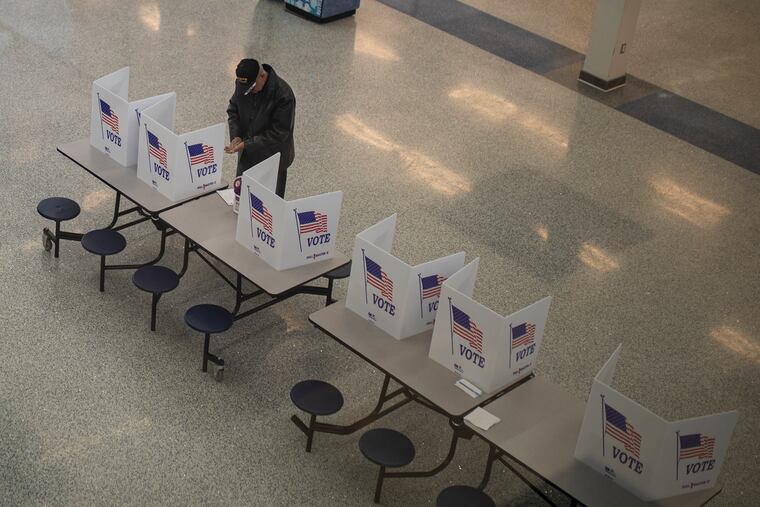

Everyday life is suspended. Democracy is not. And now it’s on officials to figure out how to keep it going as pandemic strikes during a presidential election year.

Everyday life is suspended. Democracy is not.

And now it’s on officials to figure out how to keep it going as pandemic strikes during a presidential election year.

County elections officials in Pennsylvania are urging the state to postpone the April 28 primary election because of the coronavirus, and Gov. Tom Wolf has said it’s under consideration. But the national Democratic Party has asked states not to move their elections, and lawmakers in Harrisburg, especially Republican ones, appear so far unwilling to take such drastic action.

A handful of states, including Maryland — which had been scheduled to vote the same day as Pennsylvania — have postponed their primaries. The Republican governor of Ohio decided to delay that state’s Tuesday primary hours before the polls were scheduled to open. In Pennsylvania, a special state House election went forward in Bucks County after local officials unsuccessfully petitioned a court to stop it.

During a public health crisis that has upended every corner of life in America, who has the power to change an election? Pennsylvania is now grappling with the question.

Election dates and processes are normally set by state legislatures

Pennsylvania’s primary election date is set by state law — in presidential years, for the fourth Tuesday in April — and the U.S. Constitution gives state legislatures and Congress the power to set the “times, places, and manners” of federal elections.

A postponement would be virtually unassailable if the state House and Senate passed a bill to amend the election code and the governor signed it.

“That would be best,” said Adam Bonin, a Democratic election lawyer in Philadelphia. “This is fundamental American constitutionalism, that we are happiest and the system is best when all the branches have the opportunity to weigh in on a question.”

But lawmakers in Harrisburg, at least right now, don’t agree

Right now, there’s no consensus in the state legislature on what to do.

Geography, more than partisan ties, appears to explain differences of opinion. Especially in the early stages, lawmakers from unaffected areas had expressed skepticism about the severity of the coronavirus outbreak. That was the case, for example, with some lawmakers from rural Western Pennsylvania, said Mike Straub, spokesperson for the House Republicans.

“Definitely it’s more geographic for our members than anything else,” he said.

“Would you want the policies in effect in New York City to also cover some small restaurant out in the desert in Utah?” asked Rep. Russ Diamond, a Republican who represents Lebanon County, which has yet to report a case.

Lawmakers in the southeastern part of the state, which has the most cases, have particularly urged delay.

“We simply have to move it,” said Rep. Michael Zabel, a Democrat whose district includes much of Delaware County. “And if we don’t, we’re putting Pennsylvanians’ lives at risk.”

He was concerned by the “cavalier attitude” he said he observed from colleagues representing less affected counties.

But not everyone is on board yet.

“I think it’s too early to say,” Diamond said. “We had a Civil War and that didn’t delay anything. One of the bedrocks of the American democratic process is that we don’t interfere with elections, and I think that’s a pretty high bar to cross.”

Diamond introduced a resolution to — once the crisis has passed — end the governor’s emergency declaration, which ordered nonessential businesses closed.

But to some Democratic lawmakers, that proposal sends the wrong message.

“It speaks to frustration many of us in the Democratic caucus have in Republican caucuses and social media posts that aren’t recognizing the seriousness of the situation,” said Rep. Kevin Boyle, a Democrat representing Northeast Philadelphia. “I would not support that resolution in a million years.”

Straub said lawmakers were beginning to discuss how to address the primary election, and he cited the unanimous vote to conduct business remotely as proof that lawmakers across the state now understand the seriousness of the emergency.

The Democratic National Committee on Monday implored states not to move their primaries if they can instead increase opportunities for remote or mail-in voting.

But Sen. Sharif Street, who is vice chair of the Pennsylvania Democrats, says he worries about the feasibility and safety of keeping Pennsylvania’s where it is.

“I respect the perspective of Chairman Perez, but I’m more focused on what’s best for the people of Pennsylvania than I am worried about the implications of either national party, including the one I’m a member of,” Street said.

It might come down to the governor’s emergency powers.

In an emergency, the governor has expanded powers to suspend some portions of state law. Those powers could be interpreted as allowing him to put aside the Election Code and set a new primary.

It’s the second-best scenario, Bonin said, because that would give lawmakers, candidates, and potentially voters the opportunity to challenge such an order in the courts, which could bring clarity to the issue.

» READ MORE: Voters saw a special election in Bucks County as ‘just too important’ to stay home — even to avoid coronavirus

Governors have made emergency changes to election procedures before, including when Ed Rendell changed the deadline for submitting nomination petitions in 2008 due to a snowstorm. Gov. Tom Ridge took a similar action in 2000, which withstood a court challenge.

State law on the use of emergency powers is unclear, and what little precedent is available comes from isolated court decisions, said Christopher R. Deluzio, a lawyer and policy director of the University of Pittsburgh Institute for Cyber Law, Policy, and Security.

“That doesn’t strike me as a sound way to address something as fundamental as our democracy in the midst of a crisis,” he said.

After the Blue Ribbon Commission on Pennsylvania’s Election Security studied the issue, it last year recommended updating state law to provide a clear answer as to who can modify elections during emergencies.

“If people are unsure whether an election’s happening, where it’s happening, whether times have changed, that is the kind of discord that can fundamentally shake our faith in whether someone’s won an election,” Deluzio said. “We have time to plan. We have more than a month to deal with what we’re going to do around the pandemic and our election, and we should take advantage of every second we have to plan properly and give voters clear and decisive answers.”