Newly released FBI wiretap documents reveal glimpse of George Norcross-John Dougherty relationship

The filings show how the New Jersey power broker and Philadelphia labor leader raised money to support each other’s favored political candidates and leveraged their fiefdoms to advance their goals.

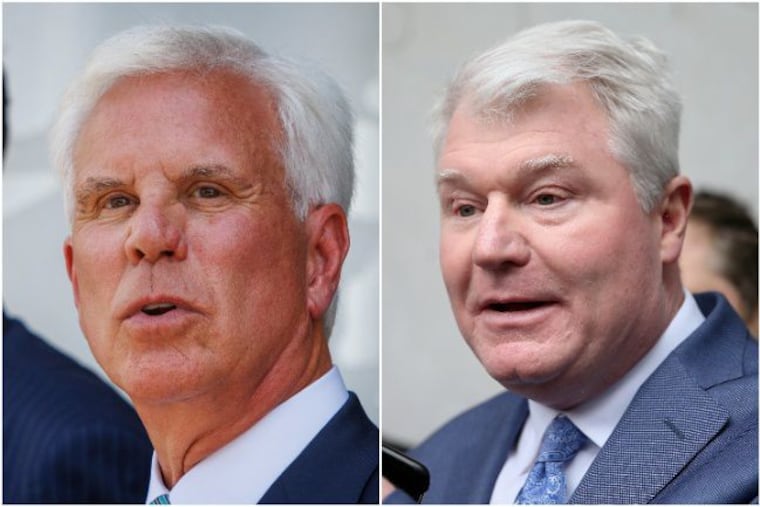

John J. Dougherty and George E. Norcross III were each at the peak of their power.

It was 2016, and Dougherty, the forceful Philadelphia labor leader and head of the city’s largest electricians’ union, had just marshaled his union’s money and manpower to help elect his brother Kevin to the Pennsylvania Supreme Court and longtime friend Jim Kenney to the mayor’s office.

Across the Delaware River, Norcross, the Camden County insurance executive and Democratic boss of South Jersey, had been quietly making moves that appeared to have put his vision for revitalizing Camden’s waterfront within his grasp.

His childhood friend, Steve Sweeney, was president of the state Senate and seen as a leading contender to succeed Republican Gov. Chris Christie, with whom Norcross also enjoyed close ties. With their help and economic development legislation that supercharged tax incentives for businesses that invested in the city, development plans in Camden — with Norcross as a major investor — were finally inching ahead.

Increasingly, Dougherty and Norcross were working together, raising money to support each other’s favored political candidates and leveraging their fiefdoms to advance each other’s personal and financial goals.

But the two power brokers shared something else that neither man knew at the time. Both were under federal investigation.

FBI agents had been surveilling their phone calls and activities for months investigating whether their activities had crossed the line into criminality. The probe never resulted in charges against Norcross, but in a June 10, 2016, application seeking court permission to continue tapping their phones, FBI Special Agent Jason Blake told a judge the investigation had “produced evidence that John Dougherty and George Norcross have exchanged things of value for official acts.”

That previously sealed document — and hundreds of pages of other heavily redacted filings from the FBI’s probe of both men — were made public for the first time last week as part of a defense filing in the New Jersey Attorney General’s Office’s racketeering case against Norcross and five codefendants.

While The Inquirer has previously reported on the existence of that earlier federal probe and the wiretaps of both men, the newly released FBI affidavits offer the most complete account to date of how a bribery and embezzlement investigation of Dougherty spawned, by mid-2016, a separate inquiry of Norcross.

Along the way, agents intercepted hundreds of private phone conversations among the two men and some of the highest-profile political figures in Philadelphia and South Jersey, including then-Mayor Kenney; then-District Attorney Seth Williams; Bob Brady, leader of the city’s Democratic Party; and members of Philadelphia City Council. Investigators captured communications with Gov. Christie, Senate President Sweeney, Philadelphia labor leader Ryan Boyer, sitting judges, state lawmakers, and more.

More intriguingly, the newly released filings offer a rare glimpse of the working relationship between Dougherty and Norcross — two of the region’s most dominant political players — and the ways in which agents believed they were willing to exert their influence to benefit each other.

The documents describe them communicating directly about raising money to help boost Kenney’s 2015 mayoral candidacy, venting about their frustrations with Brady as leader of Philadelphia’s Democratic City Committee, and discussing the possibility that Norcross’ insurance firm could land work with an agency where Dougherty held a board seat.

Throughout the recorded phone calls, Dougherty refers to Norcross in conversations with others as the “big guy across the water” and “my buddy in N.J.”

Agents described Norcross, like Dougherty, as “cautious about the people with whom he interacts.” Norcross, they said, “has the ability to hire and surround himself with individuals who are loyal to him and dependent on him for their livelihoods.”

Of particular interest to authorities was the influence Dougherty allegedly wielded over commissioners on the board of the Delaware River Port Authority, which owns and operates four bridges connecting New Jersey and Pennsylvania. Agents believed Norcross was seeking to sway board members in support of land deals necessary to his Camden waterfront development plans.

“I know how much that means to you,” the labor leader told Norcross after personally lobbying members of the board during a February 2016 meeting, according to the affidavit.

“I appreciate it,” Norcross responded, offering in the same call to connect Dougherty’s daughter, Erin, the CEO of a charter school in Philadelphia, with a nonprofit charter school network for what agents believed was a potential partnership.

Though authorities said they suspected Norcross was “benefiting from actions taken by Dougherty involving the DRPA while simultaneously offering to provide financial support to Erin Dougherty,” they never filed charges related to that supposed favor trading — or any other activity between Norcross and Dougherty that they’d flagged as suspicious at the time.

Instead, they prosecuted and convicted Dougherty on unrelated charges, including embezzling from his union and bribing Philadelphia City Councilmember Bobby Henon. They closed their investigation of Norcross and shared their recordings with the New Jersey Attorney General’s Office. State prosecutors relied on them in part to further their own investigation, resulting in a racketeering and extortion indictment against the South Jersey power broker and five codefendants in June.

Defense lawyers in the New Jersey case now maintain the earlier decision by federal prosecutors not to pursue a case against Norcross suggests they concluded that he’d committed no crimes. The attorneys are seeking to use that stalled earlier probe to undercut state prosecutors’ current racketeering case.

“Two things are clear from these transcripts: John Dougherty spoke to many, many people and none of the things Dougherty and George discussed was ever charged,” Norcross attorney Michael Critchley Sr. said in a statement Wednesday. “When people make allegations, those allegations should be reviewed — and after reviewing the facts, investigators declined to move forward.”

Regardless, federal investigators said at the time, Dougherty appeared to believe work he put in for Norcross would pay dividends for himself down the line.

As he told an associate while he recounted his purported 2016 lobbying of the DRPA on Norcross’ behalf: That “is the way the game is played.”

Power brokers on opposite sides of the river

Dougherty and Norcross have long both been involved in politics and labor in the region.

Over a quarter century, Dougherty, 64, built Local 98 of the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers into a political powerhouse that, through campaign contributions and Dougherty’s tireless networking, helped elect officials at all levels of government in Pennsylvania.

Camden native Norcross — the 68-year-old son of a labor leader, executive chairman of insurance brokerage Conner Strong & Buckelew, chair of the board at Cooper University Health Care, former longtime member of the Democratic National Committee — built the Democratic machine in South Jersey, helping the region punch above its weight in Trenton.

Norcross in 2012 joined a group of investors who bought The Inquirer, helping fuel speculation about his deepening interest in affairs in Philadelphia. He sold his stake two years later after a court fight for control of the company.

By 2016, his attention was focused on an ambitious plan to build office buildings, apartments, and shops along the Camden waterfront. Officially led by Philadelphia-based developer Liberty Property Trust, the negotiations over the proposed redevelopment now make up the backbone of the New Jersey Attorney General’s Office’s case against him.

» READ MORE: ‘Are you threatening me?’ Surprise recordings are at the heart of prosecutors’ case against George Norcross.

The FBI wiretap affidavits include new details about Dougherty’s apparent role in one piece of the plan. Norcross hoped to erect an 18-story office tower, which would serve as headquarters to his insurance firm and two other businesses led by his partners.

Norcross and fellow investors had purchased the nearby Ferry Terminal Building and inherited a long-term lease on a parking lot. But Liberty needed that lot for its broader development, so the Norcross investor group agreed to give up its lease as long as Liberty found replacement parking. The developer turned to the Delaware River Port Authority, which owned a three-acre lot nearby. Investigators believed Norcross was eager to see that happen.

The DRPA is governed by a 16-member board, with most of the commissioners appointed by the governors of Pennsylvania and New Jersey. Norcross held sway with DRPA’s New Jersey commissioners, agents said in their affidavit. But they suspected he needed assistance in convincing the Pennsylvania members of the board to agree to sell the land required for the plans to proceed.

That’s where Dougherty came in. A former Pennsylvania DRPA commissioner, he continued to hold influence over board decisions as the designated proxy of DRPA board member and Pennsylvania Auditor General Eugene DePasquale. And he maintained close ties to many of the other board members from his state, chiefly fellow labor leader Ryan Boyer, who at the time was head of the Laborers District Council.

“You know this is a gigantic deal for Jersey,” Dougherty recalled telling members of the board as he described a Feb. 10 meeting in which he encouraged them to agree to the sale on Liberty Property Trust’s proposed terms. Recounting the meeting to an associate afterward in a call caught on the wiretap, Dougherty acknowledged “there was a couple of issues” that “the guys [from] Pennsylvania had that could have been a … hang-up.”

He recalled telling them: “... [L]et’s sell off everything, let them build whatever they want.” In the end, though, Dougherty concluded, “I think the guys from Jersey will … be able to buy the parking lot and start their development.”

“Look, this is significant. Nobody wants this more than me,” Dougherty said as he delivered the news to Norcross by phone later that day. “Coming from Philly … I want the other side of the river to boom. … I want this building, worth a lot of money.”

FBI agents listening into that call suspected at the time that Dougherty had more than just civic interest in mind as he assisted Norcross in closing the deal, according to the wiretap affidavits. During the same call — just moments before Dougherty had updated Norcross on the land deal’s progress — Norcross offered to connect Dougherty’s daughter, Erin, and the charter school she ran in Philadelphia with a successful charter operator in New Jersey.

“I have the person from [the] KIPP [Academy network] who runs our whole facility in Camden, a really sharp guy,” said Norcross, who through his foundation had helped found a KIPP school in the city.

He eventually told Dougherty he had set up a meeting between her and his contacts in the organization.

Erin Dougherty in an interview this week described it as a tour of a KIPP campus and said that at no point was she considering or seeking a partnership with the organization.

A few weeks later, on March 16, the DRPA’s commissioners voted to approve a resolution to open negotiations with Liberty and the Camden Redevelopment Agency — which also held an interest in the property — to sell the parking lot. As part of the process, the port authority had commissioned an appraisal that valued the property at $2.3 million. The DRPA’s interest was valued at $800,000.

That fall, the DRPA sold the plot to Liberty for $800,000. Norcross and his partners bought it from the development firm two years later for $350,000 — or 15 cents on the dollar of the original $2.3 million appraisal, The Inquirer reported in 2019.

Norcross’ lawyers have described his investor group’s deal with Liberty as one piece of a complex series of transactions. The Norcross group spent $450,000 on repaving and environmental issues, his lawyers have said.

DRPA CEO John Hanson has said the agency obtained fair market value, saying that the port authority’s rights to the parcel were tenuous — because they were tied to a project that the agency had since abandoned — and that the parking lot was a nuisance. He maintained he didn’t know at the time of the sale that Norcross would ultimately end up with the property.

In an interview Monday, Hanson said he’d never spoken with John Dougherty about the parking lot. Agents said the union leader attended multiple board meetings during the period of the negotiations.

“I would say this was likely puffing to gain favor with somebody, or to gain a negotiation advantage,” Hanson said. He added that he’s never been contacted by Norcross about DRPA business.

Contracts and campaign cash

FBI agents in 2016 were also tracking other ways Dougherty and Norcross appeared to be working together to advance each other’s business and political interests.

In one March call detailed in the affidavits, Norcross asked Dougherty about projects at the Philadelphia Regional Port Authority, a state agency for which Dougherty was a board member.

“We’d love to do the construction work once you make a choice,” said Norcross, whose insurance firm offers construction risk management services.

“Yes,” Dougherty replied.

Blake, the FBI agent, wrote that he believed this showed Dougherty’s willingness to potentially use his influence to steer business to Norcross’ firm. The affidavit did not say whether Norcross’ firm ever formally pursued a contract or whether the port authority ultimately awarded one. Port Authority officials were not immediately able to say whether Norcross’ firm was awarded work during that period.

Investigators also probed campaign contributions that Dougherty and Norcross appeared to be arranging in support of each other’s favored political candidates. While such fundraising is legal, agents told a judge in the wiretap affidavits that they suspected one or both of the men were attempting to obscure the true source of those funds by passing them through other entities and believed the end goal was expanding their influence over public officials.

As Jim Kenney vied in the 2015 Democratic primary for mayor of Philadelphia, Dougherty and his union emerged as early supporters.

“I should have 500 coming your way shortly,” Norcross told Dougherty during an April 30, 2015, phone conversation about the race, just over two weeks before the election. Later that evening, Norcross texted: “Package sent.”

The next day, a Dougherty-affiliated political action committee — Building a Better Pennsylvania — received a $500,000 contribution from a political nonprofit based in Washington, D.C., called The Turnout Project, which had been formed just a few weeks prior.

Its fundraising consisted of money donated by “labor unions, law firms, and businesses with close ties to George Norcross and his brother Philip Norcross,” including a PAC affiliated with the Carpenters union in New Jersey, according to the June 2016 affidavit written by Blake, the FBI agent.

The New Jersey Carpenters’ support for Kenney, in particular, caused a stir, because the union’s Philadelphia local, led by Ed Coryell Sr., had thrown its support behind another candidate. The split came amid tension over labor strife at the Pennsylvania Convention Center, where Coryell’s members had lost the right to work in 2014 after the union did not sign onto new work rules.

Other unions, including Dougherty’s Local 98, crossed the picket line and continued to work. Months after Kenney’s victory, the United Brotherhood of Carpenters ousted Coryell as chief and Philadelphia-area locals were closed, with their assets and members divided among several regional councils.

Though The Inquirer and other news outlets have previously reported on the Turnout Project’s contribution and Norcross’ possible involvement was the subject of speculation in political circles at the time, the South Jersey power broker’s role had not been publicly confirmed, as he didn’t personally donate any funds and wasn’t listed on any finance reports.

At the time, Norcross distanced himself from the Carpenters’ donations. In response to a Philadelphia Magazine article about the matter, Norcross told the blog Big Trial there was “absolutely no proof” that he lined up the money and called it “absurd” to think “the Carpenters did something because George Norcross orchestrated it.”

Norcross added that he’d “known Jimmy for 20 years.”

Months later, in the fall of 2015, Norcross raised money for Dougherty’s brother Kevin’s successful campaign for Pennsylvania Supreme Court, according to the affidavit. “Checks on the way. Just got legal clearance,” Norcross texted John Dougherty on Oct. 26.

Norcross’ assistant told the labor leader in a phone call that she had three checks for him to pick up totaling $45,000. Dougherty told an associate that an even bigger windfall was coming: $100,000 from Norcross and $75,000 from Sweeney, the New Jersey Senate president.

When Norcross’ allies were fundraising for Sweeney and Norcross’ brother Donald, a Democratic member of Congress, the next year, they hit up Dougherty to return the favor. In April 2016, Dougherty’s Local 98 donated $100,000.

“I believe,” Blake, the FBI agent, wrote in his wiretap affidavit, “this was … directed by Dougherty as a favor to George Norcross.”

Their discussion of politics wasn’t all about money. In a May 2016 call quoted in the wiretap, Norcross and Dougherty groused about the current leadership of Philadelphia’s Democratic Party. Both expressed concerns over Brady, the party’s chair, and his fundraising ability.

“There is nothing positive happening there,” said Dougherty, whose relationship with Brady had long been contentious. “Bob has lost control of the party.”

Later in the conversation, Norcross added: “That is why you got to get rid of him.”

‘The guy’s buying up the world’

By the spring of that year, their attention had turned mainly to the upcoming Democratic National Convention in Philadelphia.

To cap off the July event, Norcross was preparing to host a blockbuster concert featuring Lady Gaga, Lenny Kravitz, and DJ Jazzy Jeff at Camden’s BB&T Center. He told others he’d be giving away 25,000 tickets.

It was an opportunity for Norcross — and the event’s other sponsors, including PhillyVoice, a digital news outlet run by Norcross’ daughter Lexie — to showcase the city while the eyes of the nation were on the region. But it also afforded Norcross and Dougherty the opportunity to celebrate their party’s success and the ties they’d forged over the last several months.

“There’s going to be some access. There’s going to be some VIP stuff,” Dougherty told a fellow union leader in the run-up to the event. “It’s always nice when you need that big lift, and the guy’s buying up the world.”

Norcross sought help from Dougherty and others to defray the $2.5 million cost of renting the venue and putting on the show. And Dougherty, according to the affidavits, provided $300,000. As the concert drew closer, Norcross told Dougherty on July 1 he could “make you, the mayor, whoever you want gatekeeper” of certain tickets. Dougherty shared the news with Kenney that evening.

“He’s gonna run a thousand tickets through me,” Dougherty said, “which I’m gonna run through you.”

“Right, I gotcha. Yea,” Kenney replied.

“It’s all good,” Dougherty said. “It’s all good.”