More ‘injured on duty’ police officers are back on the force following Inquirer investigation, city audit

Compared to 2021. weekly injury lists now include 300 fewer officers who are unable to work. “We need folks to do the job that they took an oath to do," said Interim Police Commissioner John Stanford.

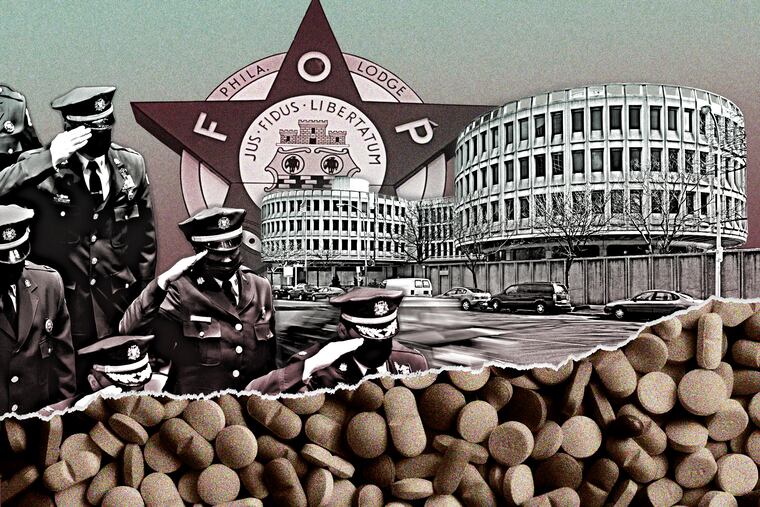

Former Philadelphia Police Commissioner Charles H. Ramsey once called it “the biggest scam going” — a state disability benefit for first responders that enables city officers to collect inflated paychecks while out of work, sometimes with dubious injuries.

For nearly two decades, city and police union officials have argued about the flaws of the Heart and Lung benefit system, while the number of police officers who weren’t available for work swelled to alarming levels.

An Inquirer investigation, MIA: Crisis in the Ranks, found that by the fall of 2021, 652 officers were listed as too hurt to work. All told, 11% of Philadelphia’s total police force was missing, vastly higher than other major cities like Chicago (3.3%), Portland, Ore. (1.9%), Tampa, Fla. (1%), and Phoenix (0.6%).

The newspaper found that at least 74 officers had been unavailable for two or more years, while doctors who had been selected by the Fraternal Order of Police Lodge No. 5 to treat their injured members had been involved with questionable practices; one had even falsely claimed to be a Philadelphia police officer when she was arrested on a DUI charge in 2020.

Now, city records reviewed by The Inquirer show that the number of cops listed as injured on duty during the summer had plunged 46% from late 2021, meaning about 300 fewer officers were out of work each week.

The number of officers who were listed as available to testify in court while they recovered from injuries has also increased dramatically, from just 64 during that same period of 2021, to now more than 200.

The injury data began sloping downward last year, after the first installment of the newspaper’s investigation, which explored multiple instances of officers who had worked second jobs while they collected the Heart and Lung benefit — a violation of police policy.

More recently, the city contracted with two Temple occupational health doctors, Howard Rudnick and Christopher Goodwin, to treat injured officers.

Rudnick and Goodwin replaced Rocco Costabile and Richard Berger, two other Heart and Lung doctors who had practiced at a small office, Holmesburg Family Medicine, which abruptly closed its Frankford Avenue doors in July 2022, making the process of returning officers to work even slower.

On Friday, John Stanford became the city’s interim police commissioner, following the resignation of Commissioner Danielle Outlaw.

Stanford said The Inquirer’s reporting “obviously made some people aware” of problems with the Heart and Lung system.

“It’s a good thing,” he said, in reference to officers returning to work. “We need folks to do the job that they took an oath to do.”

A class of 93 cadets enrolled in the police academy last week, but the force is still “down significantly,” Stanford said. The department has about 6,500 employees but is budgeted for 7,400; more than 800 officers are scheduled to retire within the next four years.

“Every little bit helps,” Stanford said.

“I’ve talked to so many men and women who get nicks and bumps and bruises, but they jump right back into the mix and they do the job,” he said. “They get frustrated knowing that people have abused the system.”

Roosevelt Poplar, an FOP vice president, said he believes that the lower injured-on-duty figures can be attributed to a gradual reduction in medical procedure backlogs that were caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The union, he said, wants to work with the city and PMA — a third-party company the city pays $6 million a year to help manage the Heart and Lung program — to streamline the injury claim process.

“We’re trying to get to where we’re all straight down the middle on this,” Poplar said. “If an officer is injured, we want to protect them. If not, we want them back to work. We don’t condone people who put us in a spot where they make us look like we’re bad union reps.”

A tangled system

A succession of police commissioners — from Ramsey to Christine Coulter and Outlaw — have expressed frustration with the Heart and Lung benefit. There is no limit on how long cops can remain out of work, or how many times they can submit a claim during their careers. And thanks to federal and state tax breaks, officers see their pay increase by about 20% while they’re out of work.

Judges, prosecutors, and defense lawyers have separately complained that the missing officers cause criminal cases to be delayed or dismissed.

The number of reported police injuries had fallen 30%, from 1,265 in 2009, to 884 in 2021. Despite fewer cops being injured on the job, the total number of days that they stayed out on Heart and Lung had nearly tripled.

Coulter has said that she thought it was time to end the tax-free perk, to “disincentivize staying out beyond the point you’re well.”

Outlaw, who left to work for the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, once recalled her reaction to learning about the benefit system’s rules after she was hired in Philadelphia in 2019: “It blew my mind,” she said. “I said, ‘You guys know this isn’t normal, right?’”

Poplar argues that police officials’ criticism of the benefit has been misguided.

“They have their version, we have our version,” he said.

The union has long insisted that, before 2004 — when Philly police officers first became eligible to receive the state benefit — city doctors rushed injured cops back to work before they were healthy.

“They’re quick to say people abuse it, but they’re not protecting the ones who aren’t abusing it,” Poplar said. “Do you want officers out there with torn muscles?”

“Nobody wants to go back to that,” Stanford said. “But we also don’t want to have the system being abused.”

The Inquirer found that some officers managed to engage in strenuous physical work while they were supposed to be too hurt to do police work — including one who competed in a traveling softball league, and was even given a defensive MVP award.

The cost to taxpayers was steep.

In October, then-City Controller Rebecca Rhynhart released an audit that showed that the city had spent $205 million since the 2017 fiscal year on salaries for injured officers. Rhynhart contended that abuse had gone largely unchecked due to poor coordination between the mayor’s office, the city’s Office of Risk Management, the police department, and PMA.

The number of officers who had missed more than a year’s worth of work due to a single injury had jumped from 10 during the 2017 fiscal year, to 124 during the 2021 fiscal year.

Following Rhynhart’s audit, FOP president John McNesby conceded that perhaps 50 or so officers could be collecting the benefit improperly for a questionable injury.

“We need to get those cops back to work, and we’re willing to sit down starting this afternoon and put some of them back to work,” McNesby said at the time.

(Terry Reid, the FOP’s longtime disability coordinator, was fired by McNesby earlier this year, after the family of a late police officer accused Reid of trying to scam the officer’s widow out of $20,000.)

Rhynhart said on Monday the new numbers “confirm the findings of the audit that it can be managed better,” that the problem was more extensive than a few dozen problem officers.

“The goal is to get any and all officers that can do the job back to work to support all the other officers that are working so hard,” she said. “The fact that it’s back down to around the 350 level does show that there was some oversight issue.”

Poplar estimates that 150 officers are seeking to retire from the police force due to injuries they suffered in the line of duty but face a yearslong wait before they’re approved by the city for disability and pension benefits, a backlog he said the city has done little to resolve.

“We have to try to make the system a little less complicated,” he said.

» READ MORE: Code Blue: FOP selected disability doctors who had questionable practices, sold diet pills for cash

Doctor, doctor

The FOP has had the ability to choose which doctors treat its members since 2003, when it was awarded that right as part of a legal settlement with the city. Other large cities, like New York and Chicago, don’t give their police unions such control.

The Inquirer found that five of the seven long-term doctors chosen since 2004 worked out of practices that operated lucrative diet-pill businesses for cash. One was accused in lawsuits of plying two patients with an abundance of addictive medications and sexually assaulting them. (He was not charged with a crime.) And two have struggled with financial troubles that ended in bankruptcy.

A police commander who is familiar with the Heart and Lung system, but didn’t have permission to speak about the benefit publicly, said officers had nicknamed one physician “Dr. Summeroff” — and rode generous diagnoses straight to the Jersey Shore.

Poplar said the FOP did not select Rudnick and Goodwin, the new Heart and Lung doctors.

“We need to make sure we have the right doctors,” Stanford said, “and that they assess folks the right way.”

The union has presented the city with names of additional doctors that it would like added to the disability system, but thus far, the city has not acted on those suggestions, said Joe Schrank, the union’s disability co-coordinator.

Schrank faulted the city and PMA for rejecting medical procedures that some injured officers need.

“We have to litigate it, and it ends up before an arbitrator,” he said, lengthening the amount of time that cops are unable to work.

A police official, who requested anonymity to discuss the Heart and Lung benefit, said Rudnick and Goodwin have been returning officers to limited- or full-duty work more quickly than some of their predecessors.

The faster pace has come as a surprise, the official said, to anyone who was hoping to milk the disability benefit.

“They’re not getting the candy they want,” the official said.