Tropical-storm records and Philly’s stubborn, steamy heat have ties to warm Atlantic and Gulf

Sea surface temperatures are 2 and 3 degrees above normal off the Midatlantic Coast, and that's one reason why it's felt like a rain forest around here.

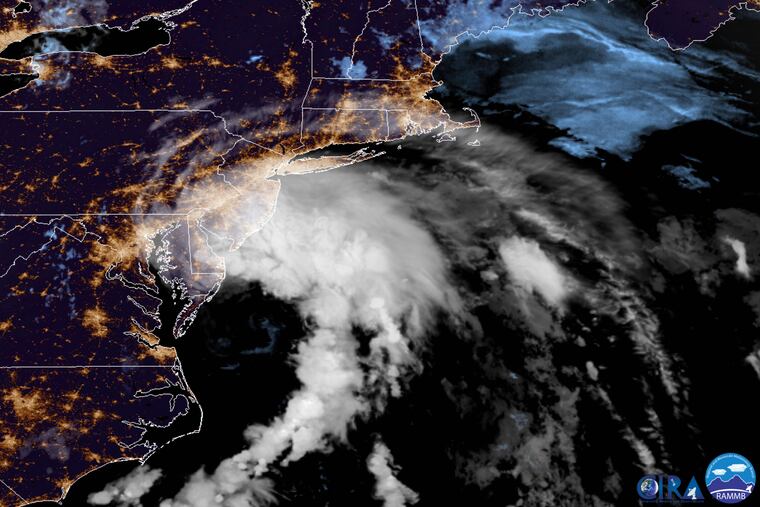

When Hanna grew into a tropical storm Friday morning, the 2020 Atlantic Basin hurricane season set yet another record for early-forming named storms, and that brisk traffic evidently has a connection to the rain-forest conditions that have settled over Philadelphia recently.

In the period of satellite records, dating to the 1960s, never had eight named storms formed before Aug. 3, and on average the season doesn’t make it to “H” until Sept. 24 in the basin, which consists of the Atlantic, the Caribbean, and Gulf of Mexico.

Neither Hanna, which hit the Texas coast as a hurricane Saturday and then got downgraded to a tropical storm, nor Gonzalo, forecast to bring tropical-storm conditions to parts of the Caribbean, is expected to affect the Philadelphia region. Both Gonzalo and Fay, which did wring out heavy rains around here on July 10, had already set records for early storms.

» READ MORE: Flood watch for Philly region as Tropical Storm Fay becomes Atlantic hurricane season’s sixth named storm

Why all the storms?

While tropical storms need a variety of ingredients to get started, they are nourished by warm waters, and right now the Gulf and Atlantic are on simmer, particularly along the Mid-Atlantic coast, where they are running as much as 4 and 5 degrees above normal.

The 30-day average Atlantic sea-surface temperatures, or SSTs, are the fourth-warmest in records dating to 1982, said Philip Klotzbach, a hurricane expert at Colorado State University, a tropical-weather research center.

The only years in which the temperatures were warmer were 2017, 2010, and 2005, the year of Katrina, when the tropical-storm numbers outran the alphabet. Klotzbach attributed the warming to a slackening of the easterly trade winds.

To at least some extent, the warm waters have countered the dampening effects of the Saharan dust layer in the atmosphere over the subtropical Atlantic. That sand and particulate matter (including camel-dung residue) ordinarily tends to inhibit storm development.

But so far the storms, all short-lived, have been able to pop up where the dust isn’t, he said.

» READ MORE: ‘Historic’ Saharan dust fills the air from Africa to the United States. But it does have a plus side.

“The above normal SSTs are certainly a significant factor,” said Dennis Feltgen, a meteorologist who is the National Hurricane Center’s spokesperson.

The Philly connection

All that warm water also is making some contribution to the siege of sultriness in the Philadelphia region, particularly at night.

“It certainly does play a role,” said Nicholas Carr, a meteorologist with the National Weather Service in Mount Holly. The nearby offshore SSTs are in the upper 70s, he said, and near 80 in the shallower depths.

Combined with the subtropical air imported from the Gulf, all that warm water has been a rich source of atmospheric moisture bathing Philadelphia. When it hasn’t been raining, it’s been soaking our clothes.

And it has consistently limited overnight cooling. All the vapor in the air inhibits the daytime warmth from escaping into space. The official temperature in Philadelphia hasn’t dropped below 74 in a week, and isn’t forecast to do so until at least Thursday morning, if then.

“The low temperatures are modulated quite a bit by the amount of moisture in the air,” Carr said.

» READ MORE: Philly heat emergency continues; strong storms possible late Wednesday and Thursday

Given that sequence and daytime highs in the 90s, the weather service might end up issuing heat advisories Sunday and Monday, he said, even though the heat indexes might fall short of the advisory criteria.

As of Sunday morning, the weather service wasn’t anticipating “hazardous” conditions, but said heat index values may reach 105 on Tuesday.

Health experts say hot nights are especially dangerous for houses without air-conditioning because they don’t give houses a chance to cool off before the sun returns to work.

The heat should back off some at midweek, but the hurricane season is another story. The Saharan dust still is offering a measure of protection.

“We’re still going to be seeing these outbreaks,” said the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Jason Dunion, a Saharan Air Layer specialist with the Hurricane Research Center. Once the Saharan dust backs off, the hurricane season tends to fire up. That could happen in a few weeks. On average, the first hurricane, a storm with winds of 74 mph or better, forms Aug. 10.

Said Dunion, “There’s almost this switch point that happens in mid-August.”