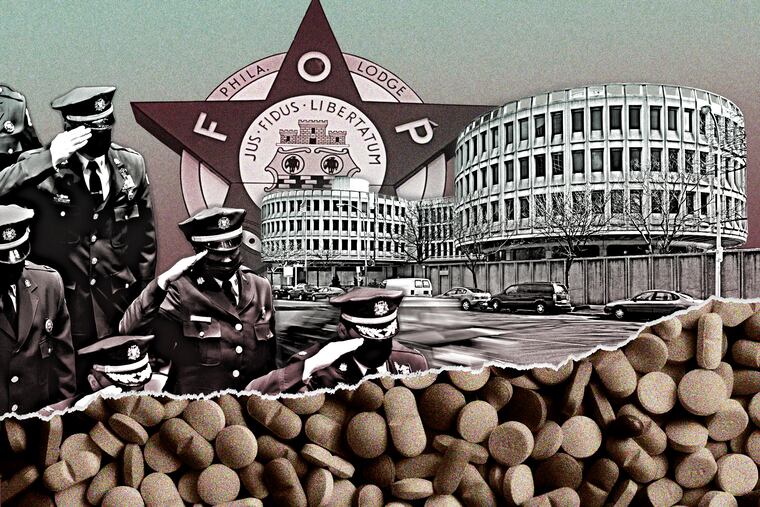

Philly has spent $205 million on salaries for injured police since 2017. An audit found little is done to prevent fraud.

Oversight of a police disability benefit is inadequate, allowing abuse to go unchecked, according to City Controller Rebecca Rhynhart.

For nearly two decades, top city officials have argued that a generous but loosely controlled state disability benefit meant for injured Philadelphia police officers has been an easy target for abuse.

But an audit of police spending, released Tuesday by City Controller Rebecca Rhynhart, has found that the cost to taxpayers is far steeper than previously imagined — and that between unreliable data and bureaucratic finger-pointing, little is being done by the city or the Police Department to root out or identify fraud among officers who claim to be too hurt to work.

Since the 2017 fiscal year, the department has spent a staggering sum on salaries of officers who have been designated “injured on duty,” or IOD: $205.5 million. The annual spending on those officers reached a record high of $44 million during the 2021 fiscal year, the audit shows, and is projected to climb even higher by the end of this fiscal year, to more than $50 million.

» READ MORE: The understaffed Philly Police don’t evaluate their main patrol and crime-fighting strategy, city controller finds

Other trends lurk behind the large dollar signs.

The number of officers who have missed more than a year’s worth of work due to a single injury has skyrocketed, from 10 during the 2017 fiscal year, to 124 during the 2021 fiscal year, according to the audit.

And the controller’s office also found that the average number of officers who are listed as “no duty” — meaning they can’t complete even menial tasks, like testifying in court or filing paperwork — has soared over the last 13 years from 234 to 572.

The audit echoes reporting that The Inquirer has done in its series MIA: Crisis in the Ranks, an exploration of Pennsylvania’s Heart and Lung benefit, which allows police officers and firefighters to collect their full salaries — along with a 20% raise, in the form of tax breaks — after they have been injured in the line of duty.

Some officers have worked second jobs while they collected the disability benefit, in violation of police policy, while others have filed multiple claims for questionable injuries. There is no limit for how long officers can remain on Heart and Lung, or on the number of claims they can submit during their careers.

» READ MORE: More than 650 Philly cops say they’re too hurt to work. But some are holding down second jobs.

The Inquirer investigation found that Philadelphia has a vastly higher percentage of its total police force out of work due to injuries, 11%, compared with other major cities such as Chicago (3.3%), Portland, Ore. (1.9%), Tampa, Fla. (1%), and Phoenix (0.6%).

Police Commissioner Danielle Outlaw called abuse of the benefit “absolutely repulsive” and directed Internal Affairs to investigate some officers who were identified by The Inquirer. At least one case has been referred to the District Attorney’s Office.

» READ MORE: ‘Absolutely repulsive’: Outlaw slams cops who abuse Philly’s injured-on-duty benefits

Rhynhart, however, found that there’s been little meaningful oversight of the benefit.

Data maintained by the Police Department’s safety office about injured officers are “minimal, and in some cases unreliable,” riddled with human errors, according to one portion of the audit.

The city’s Office of Risk Management, meanwhile, told the controller’s office that it has no formal investigative process to follow if it suspects an officer is taking advantage of the Heart and Lung system. And even if Risk Management confirms that an officer is abusing the benefit, the worst outcome the officer might face is simply being told to return to work — and the officer can appeal that decision to an arbitrator. (The arbitration results are not tracked.)

PMA, a third-party company that the city pays more than $6 million a year to help administer Heart and Lung benefits, also doesn’t have a formal process for investigating fraud, according to the audit.

To better identify cases that warrant further investigation, Rhynhart recommended that the Police Department and the city’s Office of Risk Management improve the “accuracy and consistency” of the data collected.

» READ MORE: Code Blue: The Philadelphia police union repeatedly recruited disability doctors with questionable practices

She also suggested that oversight be greatly improved. The current system to investigate cases of Heart and Lung, as the disability benefit is known, named after a state law, is “convoluted, lacks accountability, and does not appear to be adequate.” The process to flag potential fraud should be documented in writing and clearly identify the roles and responsibilities of each department, including Risk Management and PMA, she wrote.

None of the offices or agencies that were contacted by the controller’s office disputed that some police officers have taken advantage of benefits that were meant for colleagues who suffered serious injuries; nor did any of those offices promise meaningful accountability for the $205 million that has been spent in lost salaries since 2017.

“The current process may result in individuals who are abusing the benefit not being identified or not being investigated,” reads another portion of the audit, “and therefore continuing to use the benefit inappropriately.”

» READ MORE: Takeaways from our investigation into doctors chosen by the police union to treat injured cops

Risk Management officials complained to the controller’s office that the state isn’t providing any oversight of Heart and Lung, even though it is a Pennsylvania benefit.

Philadelphia is the only big city that allows its police union, the Fraternal Order of Police Lodge 5, to select the doctors who treat injured officers, an arrangement that has been rife with problems.

For months, the union has declined to speak to reporters about Heart and Lung abuse. But in a recent issue of Peace Officer, the FOP’s magazine, Terry Reid, the union’s disability coordinator, referenced the importance of not taking advantage of the benefit.

“Returning to work after the injury is healed,” she wrote, “is imperative.”

An FOP spokesperson said the union had no comment in response to Rhynhart’s audit.

Kevin Lessard, a spokesperson for the city, disagreed with several aspects of the audit. He said the city had questions about some of the auditors’ cost calculations, and he disputed that the city has data deficiencies, pointing out that Risk Management receives an “extensive” monthly management report on the injured-on-duty program from PMA.

In June, State Reps. Brian Sims and Chris Rabb, both Democrats from Philadelphia, introduced a bill to reduce fraud and abuse within the program. It would amend the Heart and Lung Act by requiring the treating physicians to be chosen independently, not by the FOP. The bill would also add new reporting requirements to increase transparency and require state-level auditing.

House Republicans have taken no action to move the bill out of committee.

“That is unacceptable,” Rabb said, noting the conservative Republican “mantra about smaller government and addressing waste, abuse, and fraud.”

Rabb said he intends to keep pushing to fix the problem, with the Philadelphia Police Department understaffed and millions of dollars being wasted.

“That money could be going toward effective policing and going after the bad guys,” he said.

Staff writer Anna Orso contributed to this article.