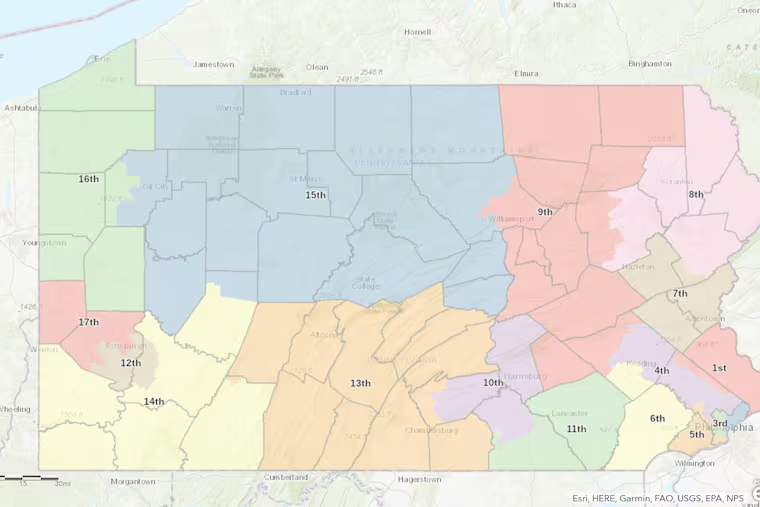

Pennsylvania has a new congressional map that will keep the state intensely competitive

The map slightly favors Republicans — with some important wins for Democrats.

» READ MORE: Is the new Pennsylvania congressional map better for Democrats or Republicans? We tested it.

The Pennsylvania Supreme Court has selected a new congressional map that will shape power and politics for the next decade, one that’s largely based on the current map and slightly favors Republicans — but with some important wins for Democrats.

In a 4-3 decision Wednesday, the court chose a map that was drawn by a Stanford professor and proposed by Democratic plaintiffs. It’s a major decision for the justices, one that will draw intense political scrutiny for the court’s elected Democratic majority. It also left the state’s May 17 primary in place, despite worries it would need to be delayed.

Congressional maps are redrawn every decade to reflect changes in population, and Pennsylvania has a history of partisan gerrymandering — drawing maps to unfairly favor one political party. With the state losing one of its 18 seats in the House of Representatives, the new districts will help determine control of Congress and how communities are represented in the years to come.

With at least four competitive House districts, Pennsylvania is a key battleground in this year’s campaign for control of Congress, with Republicans needing to gain just five seats nationwide to take the majority.

The new map was drawn by Jonathan Rodden, a well-known Stanford expert on redistricting and political geography. Rodden drew the map based on the current one, using a “least-change” approach.

It creates nine districts that voted for Donald Trump in 2016 and 2020, and eight that voted for Hillary Clinton and Joe Biden, according to a detailed data analysis conducted for The Inquirer by the nonpartisan Princeton Gerrymandering Project. It slightly favors Republicans on multiple measures of partisan skew, according to the analysis.

Looking at the two-party vote share in the two most recent presidential and U.S. Senate elections, The Inquirer classifies six of the districts as strongly Republican, five as strongly Democratic, and three each as leaning Democratic and Republican. Four districts in the new map are so closely divided that either party could realistically win them, the same as in the previous version, and a few others could become competitive in wave elections.

Unlike redistricting in some other states this year, the new Pennsylvania map doesn’t reduce the number of competitive swing seats.

But there are some individual winners and losers within the parties.

Two Republicans, Fred Keller and Glenn “GT” Thompson, were drawn together in central Pennsylvania. Keller quickly announced that he would run in the newly drawn 9th District instead, which includes most of the population of his existing one. That would pit him against fellow Republican Dan Meuser, who also said Wednesday that he’d run for reelection. That effectively ensures at least one Republican will be losing his job.

In Northeastern Pennsylvania, Rep. Matt Cartwright, one of the country’s most vulnerable Democrats, avoided a significant shift to the right for his district. But another at-risk colleague, Susan Wild, saw her Lehigh Valley district become a bit more conservative.

Pennsylvania has a Democratic voter registration edge, and the map largely reflects its swing-state status. And while party registration favors Democrats, political geography helps Republicans. The new map, though, helps Democrats at least partially overcome the disadvantage that results from having so many of their voters concentrated in and around major cities. A number of districts that might have swung rightward remain competitive.

Still, the new map leaves them defending several seats that could easily swing away from them this fall, if the political tides continue favoring the GOP.

Gov. Tom Wolf, a Democrat, applauded the ruling, calling it a “fair map that will result in a congressional delegation mirroring the citizenry of Pennsylvania.”

”With today’s decision, we could again send to Washington members of Congress elected in districts that are fairly drawn without favor to one party or the other,” he said in a statement.

Republicans immediately criticized the court for selecting a map supported by a national Democratic group and for not following the recommendation of a conservative lower-court judge to pick the map passed by the Republican-controlled legislature. Wolf vetoed that map.

“Unfortunately, the map chosen by the Pennsylvania Supreme Court today is nothing but a partisan ploy in a process that should be free of political bias,” State Rep. Seth Grove (R., York), House Republicans’ point person on elections, said in a statement.

“These are nothing but partisan rubber stamps today,” said former New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie, cochair of the National Republican Redistricting Trust.

While Republicans lambasted the process, the map itself could be good for the party, Republican strategist Chris Nicholas said. “I could see a GOP 10-7 ratio after November,” he said, pointing to possible pick-up opportunities in the Lehigh Valley and outside Pittsburgh.

Much of the political landscape is unchanged for the state’s electoral battlegrounds, with competitive districts remaining roughly as competitive as before.

The Bucks County-based 1st District, for example, where Republican Rep. Brian Fitzpatrick has won voters who lean slightly Democratic, has almost the same partisan scores as before. Democratic Rep. Chrissy Houlahan’s 6th District in Chester County is also essentially the same. Republicans had hoped a rightward shift might make her vulnerable.

Cartwright, whose district voted for Trump twice, will have a new one that’s barely more Democratic than before. Still, for him the status quo is likely a relief, since his district could easily have added even more conservative territory. And it could have added Meuser, an incumbent Republican whose home is now just outside Cartwright’s district.

But the draw for Cartwright may make reelection tougher for Wild. Her neighboring district will go from 51% Democratic to 51% Republican, according to the Princeton analysis.

» READ MORE: Pa.’s new legislative maps could boost Democrats, reflecting a closely divided state with more voters of color

Other competitive districts that will continue to have similar partisan makeups include Republican Rep. Scott Perry’s central Pennsylvania district becoming slightly redder, and Democratic Rep. Conor Lamb’s district in the Pittsburgh suburbs becoming slightly bluer.

While the map merges two Republicans, no incumbent Democrats face that situation, including in Southeastern Pennsylvania, where Democrats had worried that some of their delegation, and political power, might be diluted by drawing House members together.

The map helps Republican prospects by keeping Pittsburgh in one district. That leaves one deep-blue district in the city and a Democratic-leaning swing district in the suburbs, one Republicans hope to win now that the incumbent, Lamb, is running for Senate. Many Democrats had hoped to divide Pittsburgh to create two blue seats.

But Republicans objected to how the rest of Pittsburgh’s Allegheny County was split up, arguing that it was still divided to spread out liberal voters and create more winnable seats for Democrats. The divisions of Allegheny and Montgomery Counties “are clear gerrymanders,” said Adam Kincaid, president of the National Republican Redistricting Trust.

» READ MORE: 5 takeaways from Pennsylvania’s new state House and Senate maps

Wednesday’s court decision followed a breakdown of the normal redistricting process, which is supposed to occur as legislation: Lawmakers pass a map and send it to the governor to sign.

Not this time.

Republicans who control the legislature didn’t work with Democrats when they introduced a map and then amended it — without public scrutiny — and passed it. Meanwhile, Wolf refused to negotiate directly over the districts, instead putting out a set of general principles and criticizing Republican maps without releasing his own specific ideas for districts until late in the process.

With the legislative process failing, a group of Democratic voters and a group of math and science professors filed separate lawsuits that were later combined. At the state Commonwealth Court’s request, the parties in the case — including Wolf, Republican and Democratic lawmakers, and good-government groups — submitted 13 proposals for the new map.

The Supreme Court then took over the case. Many observers had long predicted a political stalemate over redistricting that would end up before the high court.

That put the court in the crosshairs, and in the position of having to once again make not just a legal decision, but a political one.

The map the court chose came from the Democratic voters who brought the case in the first place. They’re represented by national Democratic lawyer Marc Elias and supported by an affiliate of the National Democratic Redistricting Committee, led by Eric Holder, an attorney general under then-President Barack Obama.

Wednesday’s decision didn’t come with an opinion explaining it, which the justices said would come later. Depending on how they picked the map — including which criteria they used and how they prioritized competing interests — their explanation could significantly change the legal landscape for future redistricting in Pennsylvania.

Elected Democrats hold a 5-2 majority on the Supreme Court, which has drawn intense criticism from Republicans since its 2018 decision to overturn Pennsylvania’s congressional map as an unconstitutional partisan gerrymander. The court drew a new map. Since then, Republicans have continued to attack the court for decisions they see as partisan judicial overreach, including rulings in election-related cases in 2020.