Senate acquits Trump in his second impeachment trial, a coda to a tumultuous presidency

A majority of the Senate, including seven Republicans, voted to convict Trump of inciting the Jan. 6 Capitol insurrection, but 67 votes were required for a conviction.

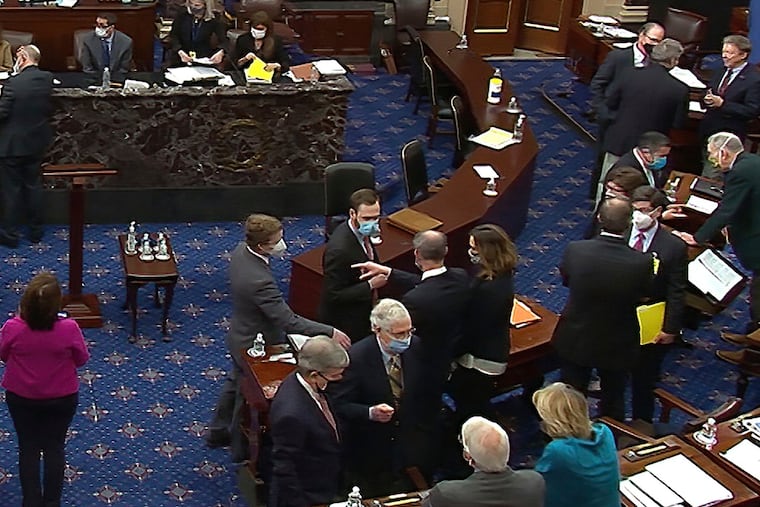

WASHINGTON — The U.S. Senate voted Saturday to acquit former President Donald Trump, ending a five-day impeachment trial by ruling that he could not — or should not — be held responsible for the Jan. 6 insurrection, when supporters fueled by his lies of a stolen election stormed the Capitol to keep him in power.

A majority of the Senate voted to convict Trump of inciting the attack, 57-43, with seven Republicans voting to convict, including Pennsylvania Sen. Pat Toomey — the most bipartisan vote to convict in any presidential impeachment trial. But 67 votes were required for conviction.

The acquittal was long expected: Few believed 17 Republicans would join the Senate’s 50 Democrats.

But Democrats hope the trial will leave a historical stain on the Trump presidency, with its meticulous re-creation of his long string of false election claims and his cheering, at times, of violence. The trial featured visceral videos of his supporters brutally attacking police, officers screaming in pain, lawmakers running for their lives, and aides barricading themselves inside offices while a mob ransacked a symbol of American democracy — all in the name of subverting the will of American voters.

The vote served as a coda, at least for now, to Trump’s tumultuous four years in office, which ended with one of the darkest days in American history.

It also showed that Trump, despite the riot and his electoral defeat, retains a powerful grip on the Republican Party. And it underscored the searing anger and division that have come to define American politics.

» READ MORE: Trump’s Philly lawyers won the impeachment trial. But they’re facing a backlash at home.

“The failure to convict Donald Trump will live as a vote of infamy in the history of the United States Senate,” Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (D., N.Y.) said after the vote. But Schumer held out hope that Trump would be “convicted in the court of public opinion” and that he would suffer “an unambiguous objection by the American people” if he ever seeks office again.

In a statement after the vote, Trump made no mention of the insurrection.

“This has been yet another phase of the greatest witch hunt in the history of our Country,” Trump said. “No president has ever gone through anything like it, and it continues because our opponents cannot forget the almost 75 million people, the highest number ever for a sitting president, who voted for us just a few short months ago.” (74.2 million people voted for Trump.)

His defense team argued that nothing Trump said “could possibly be construed” as inciting insurrection, though even many Republicans who voted to acquit disagreed.

Senate Minority leader Mitch McConnell (R., Ky.) was among them. After voting to acquit, the most powerful Republican in Washington delivered a speech supporting the arguments laid out by the Democrats who prosecuted the case, repudiating the defense by Trump’s lawyers, and excoriating Trump for what McConnell described as a “disgraceful dereliction of duty.”

”There’s no question — none — that President Trump is practically and morally responsible for provoking the events of the day,” McConnell said. “The people who stormed this building believed they were acting on the wishes and instructions of their president.”

Still, McConnell said the trial wasn’t constitutional once Trump left office — one month to the day after McConnell rejected Democratic calls to bring the Senate back into session so a trial could begin sooner.

And he raised the unlikely prospect that Trump could still be criminally prosecuted. “President Trump is still liable for everything he did while he’s in office,” McConnell said in remarks that seemed aimed at trying to undercut Trump’s powerful influence on the GOP. “He didn’t get away with anything yet.”

Democrats focused much of their closing arguments on evidence that Trump did little to stop the insurrection, even as it unfolded on live television and as his close allies called desperately seeking help. They said that showed he supported and even reveled in the violence that threatened his own vice president, Mike Pence.

“The moment we most needed a president to preserve, protect, and defend us, President Trump instead willfully betrayed us,” said Rep. David Cicilline (D., R.I.), one of the impeachment managers who prosecuted the case.

Democrats emphasized a new statement from Rep. Jaime Herrera Beutler (R., Wash.), who on Friday recounted Trump scoffing at pleas for aid from House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy (R., Calif.) during the heat of the insurrection.

“Well, Kevin, I guess these people are more upset about the election than you are,” Trump told McCarthy, according to Herrera Beutler. Senate Democrats won a vote to call her as a witness, briefly adding a dramatic twist that would have prolonged the trial. But they backed off in exchange for having her statement read into the record.

Both parties appeared eager to wrap up the trial: Democrats hoped to move to advancing President Joe Biden’s agenda, while Republicans were glad to put questions about Trump’s conduct behind them.

» READ MORE: What our reporter saw inside the House chamber as the insurrection at the Capitol closed in

Democrats argued Trump’s actions were an egregious violation of his oath of office — including months of false election claims, many targeting Pennsylvania, calling his supporters to Washington on the day Congress would certify the results, and urging them to “fight like hell” or risk losing the country.

Though he already lost reelection, Democrats said Trump needed to be forever barred from public office, lest he threaten democracy again.

“I fear like many of you do that the violence we saw on that terrible day may be just the beginning,” said Rep. Joe Neguse (D., Colo.), one of the impeachment managers. “Senators, this cannot be the beginning, it can’t be the new normal. It has to be the end.”

Trump’s defense, led by a team of lawyers from the Philadelphia region, countered that the trial was based on “sheer personal and political animus” and rushed with only limited investigation. And they pointed to examples of Democrats urging their supporters to “fight” for various political or policy causes. None incited violence or tried to undo an election result.

“At no point did you ever hear anything that could possibly be construed as Mr. Trump encouraging or sanctioning an insurrection,” said Trump attorney Mike van der Veen, a Philadelphia personal injury lawyer.

Channeling Trump, van der Veen turned the accusations on Democrats and the news media, comparing the riot at the Capitol to the sporadic violence that followed some summer protests against racism and arguing that those scenes, Democrats, and the media set the stage for the insurrection.

He called the impeachment an attempt by Democrats to satisfy their “impeachment lust” and to “shame, demean, silence, and demonize [Trump’s] supporters.”

Trump’s defense team also contended that trying a former president was unconstitutional. Numerous legal scholars from the right and left disagreed, but many Republicans pointed to that in voting to acquit. Few defended his conduct.

Democrats said such reasoning opens the door to a “January exception” allowing presidents to use their final weeks in office to cling to power by any means.

The weeks before the riot, as well as Trump’s impeachment defense itself, put many of the former president’s most inflammatory characteristics on display: an indifference to truth, disregard for the boundaries of democracy, an eagerness to stoke fury, and a rebuttal that hinged not on justifying his actions, but on turning the accusations back on his critics.

The trial was woven with Pennsylvania threads: The state was one where Trump had most ferociously attacked the election results, and much of his defense team came from suburban Philadelphia. One of the House impeachment managers, Rep. Madeleine Dean, represents a district based in Montgomery County.

» READ MORE: Bruce Castor and Madeleine Dean traveled very different paths from Montco to Trump’s impeachment trial

Ten House Republicans, out of 211, voted to impeach Trump, making him the only president to ever be impeached twice.

The trial was the first ever of a former president and unfolded with historic speed, drawing criticism from defense lawyers who argued House Democrats had moved without a thorough investigation or allowing due process.

At the same time, they effectively said Democrats had also been too slow, arguing they couldn’t try Trump after his term ended.

Unlike Trump’s first impeachment, which hinged on private discussions and an alleged scheme to pressure Ukrainian officials to smear Biden, this one centered on a deadly event that played out on live television.

Five people died, including a Capitol Police officer, and more than 100 other officers suffered injuries. The floors of the Capitol were bloodied and windows smashed. A Trump supporter was shot and killed a short walk from fleeing lawmakers.

Democrats pointed to the attack as not just a single day of unpredictable violence, but the culmination of months of Trump’s election lies, and years of his winking at and even celebrating violence. He had triumphantly tweeted a video of supporters in Texas nearly running a Biden campaign bus off the road, and joked at a rally about a plot to kidnap Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer.

They noted that there were already warnings of potential violence by Jan. 6, and that Trump went ahead with his incendiary speech anyway — using the word peacefully once in a nearly 11,000-word address while telling supporters to “fight” and urging them to march on the Capitol.

Dean said the fact that some supporters planned the attack, as the defense stressed, only proved the prosecution’s case, arguing that the rioters took their cues from Trump’s long-standing false claims. Details in the indictments of numerous Capitol attackers have supported that.

“Donald Trump invited them, he incited them, and he directed them,” Dean said. “This was months of cultivating a base of people who were violent, praising that violence and then leading them, leading that violence, that rage, straight to a joint session of Congress.”

The most damning indication of his state of mind, they argued, was that Trump said little while the riot unfolded, other than issuing two mild tweets while also sending one missive blasting Pence — even as Pence had been evacuated from the Senate and the mob hunted for the vice president. When Trump finally released a video, hours after the carnage began, he repeated his false election claims and seemed to revel in the carnage, telling his supporters, “We love you, you’re very special.”

Trump’s defense argued that many politicians use the word fight and that his words were protected by the First Amendment.

Before the final vote, Democratic impeachment managers appealed to senators to consider their place in history, and the lasting impact of their votes.

“This is almost certainly how you will be remembered,” said Rep. Jamie Raskin (D., Md.), the lead impeachment manager. “What kind of America will we be? It’s now literally in your hands.”