What COVID-19 has taught medicine in 2020

As 2020 thankfully draws to a close, here are some highlights of what science has learned from the virus that globally has infected more than 77 million people since it was first reported in China.

Just a year ago, medical science knew very little about the devastation COVID-19 can wreak. How it can destroy organs throughout the body, and even kill people who seemed to be on the way to recovery.

Initially, doctors put desperately ill patients on ventilators and scrambled for drugs that offered any hint of promise (remember hydroxychloroquine?). They called and tweeted with colleagues around the world searching for lifesaving clues.

Meanwhile, many of us over-sanitized our groceries and the mail. And many failed to appreciate the superpowers of masks.

But the pace of discovery has been phenomenal, from therapies that lessened the severity of symptoms to the collaboration that has produced remarkably effective vaccines in record time.

As 2020 thankfully draws to a close, here are some highlights of what science has learned over the past year from the virus that globally has infected nearly 79 million people, killing more than 1.7 million, since it was first reported in Wuhan, China.

Why COVID-19 is deadly to some, yet hardly touches others

From the early days in China, one of the top mysteries of COVID has been why some people become severely ill and die, while most suffer mild to moderate symptoms, or none at all. Old age and certain health conditions make people more susceptible, as with many viral illnesses, yet plenty of COVID patients meeting those descriptions recover just fine.

One factor may be right before our very noses, says University of Pennsylvania immunologist Michael Betts: masks.

In other words, even when the ubiquitous face coverings do not prevent disease, they may nevertheless help by limiting the severity of illness. The theory is that masks reduce the number of virus particles that a person ingests, which may enable the immune system to squelch an infection before it builds up steam, said Betts, a professor at Penn’s Perelman School of Medicine.

Scientists cannot directly test this idea, as it would be unethical to test a deadly virus in humans. But experiments on hamsters have found that higher “doses” of the virus lead to more severe disease. And in two real-world settings — cruise ships and food-processing plants — evidence suggests that mask wearing increases the proportion of infections with no symptoms, according to a review in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The body’s first line of defense is called the innate immune system, consisting of a variety of chemical warning signals, proteins, and other agents that attempt to fight off viral invaders. But once a virus penetrates human cells and makes lots of copies of itself, a secondary line of defense, consisting of customized antibodies, B cells, and T cells, takes on the brunt of the work. With viruses in general, if an infection gets that far, the person is more likely to feel sick.

“It certainly is a numbers game,” Betts said.

Yet with COVID, the amount of virus seems to be just part of the story. For months, Betts and others at Penn have been studying why the immune system overreacts in certain patients, leading to a cascade of harmful inflammation.

One factor may be a family of proteins in the immune system called interferons — so named because they interfere with the process of infection in various ways, such as by preventing a virus from entering a cell. Humans produce more than a dozen slightly different varieties of one class of these proteins, called interferon alpha.

Our genes determine how much we make of each, likely as a result of various infectious diseases that our ancestors survived, he said. And evidence suggests that levels of various interferon alphas may help determine a person’s ability to ward off the coronavirus.

Betts said interferons may be involved in disease severity in yet another way: by drawing friendly fire. In addition to making antibodies against the virus, some COVID patients make antibodies against their interferons — called autoantibodies because they attack the person’s own defenses.

“We are definitely making progress, there is no question,” he said. “But we still don’t know precisely what drives these different outcomes. It’s just going to take time.”

— Tom Avril

How the coronavirus spreads

Scientists have made strides in understanding coronavirus transmission — and every one of those insights has made the challenge of containing the virus harder.

Back in February, a German report that two people with no symptoms tested positive for the coronavirus was so chilling that it was published in the prestigious New England Journal of Medicine. Now, up to half of COVID-19 cases are estimated to be asymptomatic. Because such people can spread the disease without knowing it, universal masking in public is now recommended or required.

The next shattering insight into transmission remains controversial: The virus can spread invisibly indoors in microscopic droplets that are released by talking, singing, or simply breathing. These aerosols can float in the air for minutes or even hours, then be inhaled by an unsuspecting individual. In contrast, the big, wet globules expelled by a cough or sneeze mostly fall to the ground quickly, which is the basis for the six-foot social-distancing standard.

Logically, if asymptomatic people can spread the virus, then they are probably doing it just by exhaling aerosols. Super-spreader events have provided circumstantial evidence. In March, for example, a single member of a choir in Skagit Valley, Wash., infected 53 of the 61 people who rehearsed in a large room; two eventually died.

Nonetheless, it wasn’t until July that the World Health Organization — prodded by a letter from 237 experts around the globe — acknowledged “airborne transmission cannot be ruled out” and maybe indoor ventilation should be a concern. The U.S Centers for Disease Control and Prevention took until October to make a similar concession.

» READ MORE: Make this DIY air filter to (possibly) reduce your indoor exposure to coronavirus

Researching the role of indoor airflow in transmission is difficult. However, a small but growing number of meticulous investigations suggest that air-conditioning, fans, and drafts can enhance the insidiousness of the coronavirus, defying current beliefs about what kind of contact is close enough to be dangerous.

The latest such study was published last month in the Journal of Korean Medical Science. A South Korea high school student was infected after five minutes of exposure to a contagious but asymptomatic person who was sitting 20 feet away in the air-conditioned restaurant. They weren’t wearing masks but had no direct or indirect contact, such as touching the same plate or doorknob.

Meanwhile, public health officials stress the importance of frequent handwashing, even though it has not been conclusively shown that you can be infected by touching a contaminated surface, then touching your nose, mouth, or eyes.

— Marie McCullough

Testing is a testament to how much we still don’t know

When the topic is testing, it is difficult to review what COVID-19 has taught medicine without veering off into the Trump administration’s well-documented crisis mismanagement.

For example, public health officials already knew that when facing a raging pandemic, they should not ration diagnostic testing. But for many months, they had to do just that.

Initially, the federal government was the only source of COVID-19 molecular testing kits, and the kits it sent to state labs were faulty and few. Then, the government authorized emergency use of molecular tests developed by dozens of big diagnostic companies, but ramping up was hampered by shortages of everything from nasal swabs to chemicals needed to extract and copy the virus. Rationing enabled rampant spread of the virus until state governors resorted to stay-at-home orders in the spring.

“It’s insane that we have the country shut down because of swabs,” Ashish Jha, a physician then with the Harvard Global Health Institute, told the Wall Street Journal in April. “The president could use the Defense Production Act, and he could use the Army Corps of Engineers to build testing facilities.”

Federal missteps aside, testing has been a mess because experts are still learning the basics of coronavirus transmission, virulence, and immunity.

For example, experts thought simple blood tests could help compensate for the lack of molecular testing. Antibody tests, which look for signs of immune response to a virus, were hurriedly developed around the world. The goal was to track the spread of the coronavirus, and identify people who had immunity to it so they could safely resume normal life.

» READ MORE: Chester County spent $13 million on coronavirus antibody tests. Then it quietly shelved the program.

But while rapid antibody tests have transformed HIV detection, the coronavirus version has been disappointing. Accuracy is low, and uncertainty is high. How long do COVID-19 antibodies persist? What level is protective? Do asymptomatic infections confer adequate protection?

Similarly, experts such as Harvard Medical School epidemiologist Michael Mina have had high hopes for antigen testing, which detects a protein made by the virus in the early days of infection. Rapid and inexpensive, the blood tests could be used in schools, prisons, nursing homes — anywhere.

Screening millions of people every few days in hot spots would be “more than enough to suppress the outbreaks that are happening and make the country much safer,” Mina said during a lecture posted on YouTube.

In September, the Trump administration began bimonthly shipments of 140 million antigen tests to the states. But again, the lessons of the coronavirus are hard. Antigen tests are often wrong. Results may go unreported to public health authorities. And the current level of testing is not enough to put a dent in the raging pandemic, as two researchers explained in an article for The Conversation.

This month marked another step forward: approval of the first over-the-counter, at-home, antigen test. Only time will tell if DIY testing makes a difference.

— Marie McCullough

Nursing home residents have suffered terribly. But there is hope.

Even before the first case was identified in the United States, Chinese officials had made it clear that the virus was more likely to kill older people already in poor health.

Still, COVID-19′s rampage through America’s nursing homes was horrifying to watch. More than 100,000 people in nursing homes and other long-term care settings have died. Fifty-eight percent of coronavirus deaths in Pennsylvania and 45% in New Jersey involved either residents or workers at such facilities.

While it is tempting to blame these deaths on nursing home failures, research so far has found little connection between outbreaks and quality ratings or inspections, said Vincent Mor, a Brown University health services expert. Instead, he said, the evidence is “quite conclusive” that the most important factor is how much the virus is spreading in neighborhoods where staff live, because workers are the main way the disease sneaks into facilities.

Nina O’Connor, chief of palliative care at Penn Medicine and of a regional program that pairs Penn with area nursing homes, said she has seen outbreaks in facilities that seemed to be doing everything right. “I don’t think this is always within a nursing home’s control,” she said.

Mor said the problem was worse in the spring because nursing homes lacked protective equipment.

Doctors and nursing home leaders have learned a great deal about how to limit nursing home cases and treat them, O’Connor said. The game changer was widespread, frequent testing of staff, which she says nursing homes are doing better than anybody. In the beginning of the pandemic, before doctors realized how common asymptomatic cases are, nursing homes tested only residents or staff with symptoms. That often allowed the coronavirus to spread widely before it was detected. Up to 40% of infected nursing home residents, even some who are very old and frail, never show symptoms, Mor said. Big outbreaks led to large numbers of deaths.

Now cases are caught faster, and residents are sequestered in three groups: those known to be infected, those who have been exposed, and people who test negative and have no symptoms.

Death rates are down. Mor, who has studied residents who tested positive for COVID-19 at Genesis HealthCare facilities, said mortality has dropped from about 30% in April to 12% in October.

One factor, O’Connor said, may be that the most vulnerable residents have already died, but she thinks care has also improved. Doctors are identifying patients who need extra care more quickly and they know better who should get extra oxygen and steroids.

Nursing homes have just started using monoclonal antibodies, newly approved treatments that can boost immune response early in infection. These treatments have been underutilized in the general public because they are given intravenously, and patients are often identified too late. But, O’Connor said, nursing homes, where patients are tested frequently and infusion is readily available, are perfect settings for the drugs.

Mor said there was “chaos” and a lot of fear in nursing homes in the early months. He thinks care is better now because workers have settled into routines. He also thinks widespread masking may be leading to lower exposure to the virus.

One of the biggest lessons of the year had nothing to do with new drugs or tests. It is about the power of human contact. O’Connor has watched some nursing home residents decline faster than they normally would have because their depression and dementia worsened without visitors, activities, and a sense of purpose.

» READ MORE: The coronavirus pandemic is killing people with Alzheimer’s who didn’t even contract the virus

“I think we’ve learned about the incredible impact of isolation on these older adults,” O’Connor said. “Isolation is just as dangerous as the virus in some of these residents.”

— Stacey Burling

Pandemic adds pressure to an already-strained mental health system

The pandemic has laid bare what experts long knew about mental health: The system is strained and often young people suffer most.

As the coronavirus spread, mental health experts warned of the negative effects that isolation, unemployment, and increased anxiety could have on people’s emotional well-being.

Health-care workers, who already have high rates of burnout, made physical and emotional sacrifices to treat COVID-19 patients. Young people dealt with the sudden loss of graduations and job offers, and mental health-related visits to the emergency room increased for children. The gaps in access to behavioral health treatment widened in communities of color, which were disproportionately affected by the pandemic. In mid-April, suicide prevention hotlines reported getting more calls, and by August nearly 41% of adults surveyed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported at least one adverse mental or behavioral health condition.

The effects of the pandemic on mental health are so severe that China, where mental health discussions once were rare, has begun confronting the issue. But while mental health problems are not as stigmatized in the United States, where suicide rates have increased 30% between 2000 and 2016, existing services do not meet demand, advocates say.

Telemedicine and teletherapy have eased access for some, but others who are most at risk, like those who are in unstable housing situations or need residential treatment, are still struggling. The increases in relapses, drug use, and domestic violence are all related to declining mental health, said Dan DeJoseph, the medical director at Delaware Valley Community Health.

“In the last month or so, a lot of our patients are doing worse,” DeJoseph said. “I’m getting many more emergency room summaries of patients going in with overdoses. … I think that’s in a large part due to mental health. Their insurance statuses are fluctuating, which is a real barrier. They’ve lost their jobs, so they don’t have access to phones or computers for Zoom or FaceTime. We’re trying to make this patchwork of care work.”

— Bethany Ao

Health-care workers are tested like never before

With so much unknown about COVID-19, doctors, nurses, and technicians changed their work clothes outside their homes to protect their families. Some stayed in hotels rather than risk infecting the people they loved. But for most, quitting was never an option.

While the pandemic created solidarity in emergency rooms and intensive care units, the lack of protective equipment, as well as confusing communication, sometimes meant deep fissures between employees and hospital administrators.

“When you’re in front of a patient and the mask falls off your face, what are you going to do, cover your face with your elbow?” Celeste Bevans, a radiology technician and a representative of the Temple University Allied Health Professionals union, said in May.

Therapists heard health-care workers talk of sleepless nights and excessive drinking.

“I have a 6-year-old little girl with asthma, and the thought of making her sick keeps me up at night,” Matthew Behme, chair of general internal medicine and geriatrics at Einstein Medical Center Philadelphia, said in May. “My parents are older, and I worry so much about them. I never even conceived the idea that I might make my family sick.”

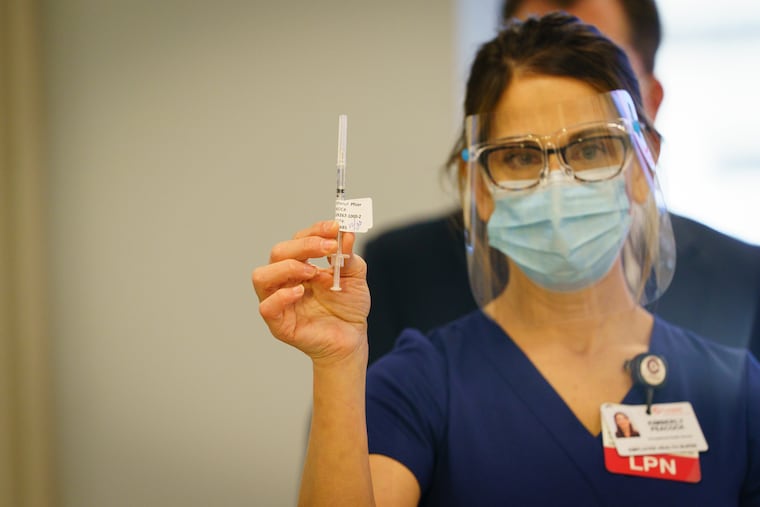

As the first vaccine shots made their way to hospitals this month, the word staffers most often used to describe their emotions after receiving their first injection was “relief.”

— Jason Laughlin

Pandemic exposed other epidemics that too often go unnoticed

Long before the coronavirus pandemic hit, Philadelphia health officials had been tracking a disturbing trend in another epidemic ravaging the city: the overdose crisis.

For many years, Philadelphia has been at the epicenter of America’s urban opioid crisis — one that’s been painted primarily as affecting white residents who initially became addicted through prescription painkillers, then switched to heroin. Indeed, white residents have long made up a majority of overdose deaths in the city.

But in the last few years, overdoses have been rising among people of color in Philadelphia. And at the height of the pandemic this spring, the overdose crisis underwent an alarming demographic shift. In the second quarter of the year, Black Philadelphians’ share of the city’s fatal overdoses nearly doubled, surpassing that of white Philadelphians.

Overdoses as a whole are on the rise this year in Philadelphia, and officials fear the total death toll will surpass that of 2017, the worst on record.

The rise in overdoses among Philadelphians is likely due to a number of factors, not all of them pandemic-related. For example, fentanyl, the powerful synthetic opioid that’s contaminated most of the city’s heroin supply, is now making its way into other drugs, and putting people who aren’t used to opioids at risk of overdose. Advocates have been sounding the alarm on fentanyl’s spread across the city for years.

And for those on the front lines who work with people in addiction, there’s a clear connection between the rise in overdose deaths among Black Philadelphians and the unique struggles that they have faced during the pandemic.

Nationwide, Black people have been more likely to contract the coronavirus and to suffer serious complications — another example of the health disparities that have plagued communities of color for years. The pandemic has thrown that injustice into even sharper relief.

“We can’t figure out how to offer [COVID] testing to people when they are not symptomatic — what does that say to a mostly Black and brown, underpaid workforce, and how are they supposed to live with that trauma, going home knowing that any day they go home to a family member, they could be infected with COVID?” Michael Hinson, the president of SELF Inc., the largest emergency housing provider in the city, said in a December interview.

“People are having to deal with not being able to work, not having economic resources. On top of homelessness, on top of joblessness, how do you cope with that? How do you not turn to something to offer you some peace?”

Preliminary national data shows that overdoses have risen throughout the country as the pandemic has spiraled, and advocates have said that it’s crucial to design lockdown measures with people struggling with addiction in mind.

» READ MORE: How the coronavirus has upended the lives of people who have no safe place to quarantine

“When you design COVID response measures, you have to keep in mind that additional measures are necessary to mitigate the negative consequences of these mandates to stay home,” said Northeastern University professor Leo Beletsky in December. People need access to [overdose reversal drugs] and treatment. People need access to economic and social supports. And in all of those, the COVID response measures are really lacking.”

— Aubrey Whelan